- Home

- P. D. James

Original Sin

Original Sin Read online

Original Sin

P. D. JAMES

CONTENTS

BOOK ONE

Foreword to Murder

BOOK TWO

Death of a Publisher

BOOK THREE

Work in Progress

BOOK FOUR

Evidence in Writing

BOOK FIVE

Final Proof

AUTHOR’S NOTE

This novel is set on the Thames and many of the scenes

and places described will be familiar to lovers of

London’s river. The Peverell Press and all the characters

exist only in the imagination of the author and bear no

relation to places or people in real life.

BOOK ONE

Foreword to Murder

1

For a temporary shorthand-typist to be present at the discovery of a corpse on the first day of a new assignment, if not unique, is sufficiently rare to prevent its being regarded as an occupational hazard. Certainly Mandy Price, aged nineteen years two months, and the acknowledged star of Mrs Crealey’s Nonesuch Secretarial Agency, set out on the morning of Tuesday, 14 September for her interview at the Peverell Press with no more apprehension than she usually felt at the start of a new job, an apprehension which was never acute and was rooted less in any anxiety whether she would satisfy the expectations of the prospective employer than in whether the employer would satisfy hers. She had learned of the job the previous Friday when she called in at the agency at six o’clock to collect her pay after a boring two-week stint with a director who regarded a secretary as a status symbol but had no idea how to use her skills, and she was ready for something new and preferably exciting although perhaps not as exciting as it was subsequently to prove.

Mrs Crealey, for whom Mandy had worked for the past three years, conducted her agency from a couple of rooms above a newsagent and tobacconist’s shop off the Whitechapel Road, a situation which, she was fond of pointing out to her girls and clients, was convenient both for the City and for the towering offices of Docklands. Neither had so far produced much in the way of business, but while other agencies foundered in the waves of recession Mrs Crealey’s small and underprovisioned ship was still, if precariously, afloat. Except for the help of one of her girls when no outside work was available, she ran the agency single-handed. The outer room was her office in which she propitiated clients, interviewed new girls and assigned the next week’s work. The inner was her personal sanctum, furnished with a divan bed on which she occasionally spent the night in defiance of the terms of the lease, a drinks cabinet and refrigerator, a cupboard which opened to reveal a minute kitchen, a large television set and two easy chairs set in front of a gas fire in which a lurid red light rotated behind artificial logs. She referred to her room as the ‘cosy’, and Mandy was one of the few girls who were admitted to its privacies.

It was probably the cosy which kept Mandy faithful to the agency, although she would never have openly admitted to a need which would have seemed to her both childish and embarrassing. Her mother had left home when she was six and she herself had been hardly able to wait for her sixteenth birthday when she could get away from a father whose idea of parenthood had gone little further than the provision of two meals a day, which she was expected to cook, and her clothes. For the last year she had rented one room in a terraced house in Stratford East where she lived in acrimonious camaraderie with three young friends, the main cause of dispute being Mandy’s insistence that her Yamaha motor bike should be parked in the narrow hall. But it was the cosy in Whitechapel Road, the mingled smells of wine and takeaway Chinese food, the hiss of the gas fire, the two deep and battered armchairs in which she could curl up and sleep which represented all Mandy had ever known of the comfort and security of a home.

Mrs Crealey, sherry bottle in one hand and a scrap of jotting pad in the other, munched at her cigarette holder until she had manoeuvred it to the corner of her mouth where, as usual, it hung in defiance of gravity, and squinted at her almost indecipherable handwriting through immense horn-rimmed spectacles.

‘It’s a new client, Mandy, the Peverell Press. I’ve looked them up in the publishers’ directory. They’re one of the oldest – perhaps the oldest – publishing firms in the country, founded in 1792. Their place is on the river. The Peverell Press, Innocent House, Innocent Walk, Wapping. You must have seen Innocent House if you’ve taken a boat trip to Greenwich. Looks like a bloody great Venetian palace. They do have a launch, apparently, to collect staff from Charing Cross pier, but that’ll be no help to you, living in Stratford. It’s your side of the Thames, though, which will help with the journey. I suppose you’d better take a taxi. Mind you get them to pay before you leave.’

‘That’s OK, I’ll use the bike.’

‘Just as you like. They want you there on Tuesday at ten o’clock.’

Mrs Crealey was about to suggest that, with this prestigious new client, a certain formality of dress might be appropriate, but desisted. Mandy was amenable to some suggestions about work or behaviour but never about the eccentric and occasionally bizarre creations with which she expressed her essentially confident and ebullient personality.

She asked: ‘Why Tuesday? Don’t they work Mondays?’

‘Don’t ask me. All I know is that the girl who rang said Tuesday. Perhaps Miss Etienne can’t see you until then. She’s one of the directors and she wants to interview you personally. Miss Claudia Etienne. I’ve written it all down.’

Mandy said: ‘What’s the big deal then? Why have I got to be interviewed by the boss?’

‘One of the bosses. They’re particular who they get, I suppose. They asked for the best and I’m sending the best. Of course they may be looking for someone permanent, and want to try her out first. Don’t let them persuade you to stay on, Mandy, will you?’

‘Have I ever?’

Accepting a glass of sweet sherry and curling into one of the easy chairs, Mandy studied the paper. It was certainly odd to be interviewed by a prospective employer before beginning a new job even when, as now, the client was new to the agency. The usual procedure was well understood by all parties. The harassed employer telephoned Mrs Crealey for a temporary shorthand-typist, imploring her this time to send a girl who was literate and whose typing speed at least approximated to the standard claimed. Mrs Crealey, promising miracles of punctuality, efficiency and conscientiousness, dispatched whichever of her girls was free and could be cajoled into giving the job a try, hoping that this time the expectations of client and worker might actually coincide. Subsequent complaints were countered by Mrs Crealey’s invariably plaintive response: ‘I can’t understand it. She’s got the highest reports from other employers. I’m always being asked for Sharon.’

The client, made to feel that the disaster was somehow his or her fault, replaced the receiver with a sigh, urged, encouraged, endured until the mutual agony was over and the permanent member of staff returned to a flattering welcome. Mrs Crealey took her commission, more modest than was charged by most agencies, which probably accounted for her continued existence in business, and the transaction was over until the next epidemic of flu or the summer holidays provoked another triumph of hope over experience.

Mrs Crealey said: ‘You can take Monday off, Mandy, on full pay of course. And better type out your qualifications and experience. Put “Curriculum Vitae” at the top, that always looks impressive.’

Mandy’s curriculum vitae, and Mandy herself – despite her eccentric appearance – never failed to impress. For this she had to thank her English teacher, Mrs Chilcroft. Mrs Chilcroft, facing her class of recalcitrant eleven-year-olds, had said: ‘You are going to learn to write your own language simply, accurately and with some elegance, and to speak it so that you a

ren’t disadvantaged the moment you open your mouths. If any of you has ambitions above marrying at sixteen and rearing children in a council flat you’ll need language. If you’ve no ambitions beyond being supported by a man or the State you’ll need it even more, if only to get the better of the local authority Social Services department and the DSS. But learn it you will.’

Mandy could never decide whether she hated or admired Mrs Chilcroft, but under her inspired if unconventional teaching she had learned to speak English, to write, to spell and to use it confidently and with some grace. Most of the time this was an accomplishment she preferred to pretend she hadn’t achieved. She thought, although she never articulated the heresy, that there was little point in being at home in Mrs Chilcroft’s world if she ceased to be accepted in her own. Her literacy was there to be used when necessary, a commercial and occasionally a social asset, to which Mandy added high shorthand-typing speeds and a facility with various types of word processor. Mandy knew herself to be highly employable, but remained faithful to Mrs Crealey. Apart from the cosy there were obvious advantages in being regarded as indispensable; one could be sure of getting the pick of the jobs. Her male employers occasionally tried to persuade her to take a permanent post, some of them offering inducements which had little to do with annual increments, luncheon vouchers or generous pension contributions. Mandy remained with the Nonesuch Agency, her fidelity rooted in more than material considerations. She occasionally felt for her employer an almost adult compassion. Mrs Crealey’s troubles principally arose from her conviction of the perfidy of men combined with an inability to do without them. Apart from this uncomfortable dichotomy, her life was dominated by a fight to retain the few girls in her stable who were employable, and her war of attrition against her ex-husband, the tax inspector, her bank manager and her office landlord. In all these traumas Mandy was ally, confidante and sympathizer. Where Mrs Crealey’s love-life was concerned this was more from an easy goodwill than from any understanding, since to Mandy’s nineteen-year-old mind the possibility that her employer could actually wish to have sex with the elderly – some of them must be at least fifty – and unprepossessing males who occasionally haunted the office, was too bizarre to warrant serious contemplation.

After a week of almost continuous rain Tuesday promised to be a fine day with gleams of fitful sunshine shafting through the low clusters of cloud. The ride from Stratford East wasn’t long, but Mandy left plenty of time and it was only a quarter to ten when she turned off The Highway, down Garnet Street and along Wapping Wall, then right into Innocent Walk. Reducing speed to a walking pace, she bumped along a wide cobbled cul-de-sac bounded on the north by a ten-foot wall of grey brick and on the south by the three houses which comprised the Peverell Press.

At first sight she thought Innocent House disappointing. It was an imposing but unremarkable Georgian house with proportions which she knew rather than felt to be graceful, and it looked little different from the many others she had seen in London’s squares or terraces. The front door was closed and she saw no sign of activity behind the four storeys of eight-paned windows, the two lowest ones each with an elegant wrought-iron balcony. On either side was a smaller, less ostentatious house, standing a little distanced and detached like a pair of deferential poor relations. She was now opposite the first of these, number 10, although she could see no sign of numbers 1 to 9, and saw that it was separated from the main building by Innocent Passage, barred from the road by a wrought-iron gate, and obviously used as a parking space for staff cars. But now the gate was open and Mandy saw three men bringing down large cardboard cartons by a hoist from an upper floor and loading them into a small van. One of the three, a swarthy under-sized man wearing a battered bush-ranger’s hat, took it off and swept Mandy a low ironic bow. The other two glanced up from their work to regard her with obvious curiosity. Mandy, pushing up her visor, bestowed on all three of them a long discouraging stare.

The second of these smaller houses was separated from Innocent House by Innocent Lane. It was here, according to Mrs Crealey’s instructions, that she would find the entrance. She switched off the engine, dismounted, and wheeled the bike over the cobbles, looking for the most unobtrusive place in which to park. It was then that she had her first glimpse of the river, a narrow glitter of shivering water under the lightening sky. Parking the Yamaha, she took off her crash helmet, rummaged for her hat in the side pannier and put it on, and then, with the helmet under her arm, and carrying her tote bag, she walked towards the water as if physically drawn by the strong tug of the tide, the faint evocative sea smell.

She found herself on a wide forecourt of gleaming marble bounded by a low railing in delicate wrought iron with at each corner a glass globe supported by entwined dolphins in bronze. From a gap in the middle of the railing a flight of steps led down to the river. She could hear its rhythmic slap against the stone. She walked slowly towards it in a trance of wonder as if she had never seen it before. It shimmered before her, a wide expanse of heaving sun-speckled water which, as she watched, was flicked by the strengthening breeze into a million small waves like a restless inland sea, and then, as the breeze dropped, mysteriously subsided into shining smoothness. And, turning, she saw for the first time the towering wonder of Innocent House, four storeys of coloured marble and golden stone which, as the light changed, seemed subtly to change colour, brightening, then shading to a deeper gold. The great curved arch of the main entrance was flanked by narrow arched windows and above it were two storeys with wide balconies of carved stone fronting a row of slender marble pillars rising to trefoiled arches. The high arched windows and marble columns extended to a final storey under the parapet of a low roof. She knew none of the architectural details but she had seen houses like this before, on a boisterous ill-conducted school trip to Venice when she was thirteen. The city had left little impression on her beyond the high summer reek of the canal, which had caused the children to hold their noses and scream in simulated disgust, the over-crowded picture galleries and palaces which she was told were remarkable but which looked as if they were about to crumble into the canals. She had seen Venice when she was too young and inadequately prepared. Now for the first time in her life, looking up at the marvel of Innocent House, she felt a belated response to that earlier experience, a mixture of awe and joy which surprised and a little frightened her.

The trance was broken by a male voice: ‘Looking for someone?’

Turning, she saw a man looking at her through the railings, as if he had risen miraculously from the river. Walking over, she saw that he was standing in the bow of a launch moored to the left of the steps. He was wearing a yachting cap set well back on a mop of black curls and his eyes were bright slits in the weatherbeaten face.

She said: ‘I’ve come about a job. I was just looking at the river.’

‘Oh, she’s always here is the river. The entrance is down there.’ He cocked a thumb towards Innocent Lane.

‘Yes, I know.’

To demonstrate independence of action, Mandy glanced at her watch, then turned and spent another two minutes regarding Innocent House. With a final glance at the river she made her way down Innocent Lane.

The outer door bore a notice: PEVERELL PRESS – PLEASE ENTER. She pushed it open and passed through a glass vestibule and into the reception office. To the left was a curved desk and a switchboard manned by a grey-haired, gentle-faced man who greeted her with a smile before checking her name on a list. Mandy handed him her crash helmet and he received it into his small age-speckled hands as carefully as if it were a bomb, and for a few moments seemed uncertain what to do with it, finally leaving it on the counter.

He announced her arrival by telephone, then said: ‘Miss Blackett will come to take you up to Miss Etienne. Perhaps you would like to take a seat.’

Mandy sat and, ignoring the three daily newspapers, the literary magazines and the carefully arranged catalogues fanned out on a low table, looked about her. It must once have been an el

egant room; the marble fireplace with an oil painting of the Grand Canal set in the panel above it, the delicate stuccoed ceiling and the carved cornice contrasted incongruously with the modern reception desk, the comfortable but utilitarian chairs, the large baize-covered noticeboard and the caged lift to the right of the fireplace. The walls painted a dark rich green bore a row of sepia portraits. Mandy supposed they were of previous Peverells and had just got to her feet to have a closer look when her escort appeared, a sturdy, rather plain woman who was presumably Miss Blackett. She greeted Mandy unsmilingly, cast a surprised and rather startled look at her hat and, without introducing herself, invited Mandy to follow her. Mandy was unworried by her lack of warmth. This was obviously the managing director’s PA, anxious to demonstrate her status. Mandy had met her kind before.

The hall made her gasp with wonder. She saw a floor of patterned marble in coloured segments from which six slim pillars rose with intricately carved capitals to an amazing painted ceiling. Ignoring Miss Blackett’s obvious impatience as she lingered on the bottom step of the staircase, Mandy unselfconsciously paused and slowly turned, eyes upwards, while above her the great coloured dome spun slowly with her; palaces, towers with their floating banners, churches, houses, bridges, the curving river plumed with the sails of high-masted ships and small cherubs with pouted lips blowing prosperous breezes in small bursts like steam from a kettle. Mandy had worked in a variety of offices, from glass towers furnished with chrome and leather and the latest electronic wonders to rooms as small as cupboards with one wooden table and an ancient typewriter, and had early learned that the office ambience was an unreliable guide to the firm’s financial standing. But never before had she seen an office building like Innocent House.

The Skull Beneath the Skin

The Skull Beneath the Skin A Taste for Death

A Taste for Death The Children of Men

The Children of Men The Part-Time Job

The Part-Time Job Death in Holy Orders

Death in Holy Orders The Victim

The Victim Shroud for a Nightingale

Shroud for a Nightingale Talking about Detective Fiction

Talking about Detective Fiction Sleep No More

Sleep No More The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories

The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories Time to Be in Earnest

Time to Be in Earnest Original Sin

Original Sin A Mind to Murder

A Mind to Murder Cover Her Face

Cover Her Face Innocent Blood

Innocent Blood Devices and Desires

Devices and Desires Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales

Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales Death Comes to Pemberley

Death Comes to Pemberley The Mistletoe Murder

The Mistletoe Murder Death of an Expert Witness

Death of an Expert Witness The Private Patient

The Private Patient The Black Tower

The Black Tower Devices & Desires - Dalgleish 08

Devices & Desires - Dalgleish 08 Unnatural Causes

Unnatural Causes An Unsuitable Job for a Woman

An Unsuitable Job for a Woman The Murder Room

The Murder Room A Certain Justice

A Certain Justice The Lighthouse

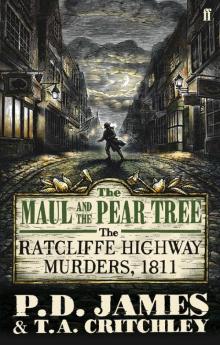

The Lighthouse The Maul and the Pear Tree

The Maul and the Pear Tree