- Home

- P. D. James

The Children of Men

The Children of Men Read online

PRAISE FOR P. D. JAMES’S

THE CHILDREN OF MEN

“James is a master of character and contributing incident, her novel from first to last is exceedingly well-wrought. Its primary pleasures are those of craft: a deft interleafing of lives, the reflective interaction of first-person and omniscient point of view, the sure voice of pace, and seamless narrative.”

—Los Angeles Times

“Graceful.… Poetic.… A riveting tale.”

—Boston Herald

“Everyone should read this book.”

—Associated Press

“Her view is Olympian.… Always she explores character, the complexities of motive, and thought and emotion; and always she wonders about the nature of humankind in general—this baffling admixture of good and evil, faith and failure, love and a murderous self-sufficiency.”

—The New York Times Book Review

“Taut, terrifying, and ultimately convincing.”

—Daily Mail (London)

“An intriguing, multi-layered work.… A worthwhile excursion.”

—Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

“Extraordinary.… Striking out alone across the blank landscape of the future, she takes no icons from the past—only skill and an adventuresome spirit, as well as a sense of what matters in the long run. It is to everyone’s benefit—hers, ours, probably homo sapiens’—that these tools turn out to be sufficient.”

—The Boston Globe

“This novel has the potential to become a classic.”

—The Christian Science Monitor

“Subtle, finely argued.”

—London Review of Books

“A vivid cast.… James evokes strong feelings about the choices people make when life deprives them of hope in a future.”

—Glamour

“Unsettling images, a brooding sense of evil.… Ms. James is one of those rare writers who is read as much for her descriptive passages as she is for her plots.”

—The New York Observer

“James keenly observes the unraveling of humankind.”

—People

“Her old strengths and vividness of characterization and mastery of storytelling propel the reader through her narrative with irresistible force.”

—The Sunday Telegraph (London)

FIRST VINTAGE BOOKS EDITION, MAY 2006

Copyright © 1992 by P. D. James

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. Originally published in Great Britain by Faber and Faber Limited, London, in 1992, and subsequently in hardcover in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, in 1993.

Vintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Knopf edition as follows:

James, P. D.

The children of men / P. D. James

p. cm.

1. End of the world—Fiction. 2. Infertility, Male—Fiction.

2. Twenty-first century—Fiction. 3. History teachers—Fiction.

4. Oxford (England)—Fiction. I. Title.

PR6060.A467 C48 1993

823′.914—dc20 92-54280

eISBN: 978-0-307-77344-9

www.vintagebooks.com

v3.1

Again, to my daughters

Clare and Jane

who helped

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

BOOK ONE

OMEGA

January–March 2021

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

BOOK TWO

ALPHA

October 2021

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

About the Author

Other Books by This Author

Also by P. D . James

BOOK ONE

OMEGA

January–March 2021

I

Friday 1 January 2021

Early this morning, 1 January 2021, three minutes after midnight, the last human being to be born on earth was killed in a pub brawl in a suburb of Buenos Aires, aged twenty-five years, two months and twelve days. If the first reports are to believed, Joseph Ricardo died as he had lived. The distinction, if one can call it that, of being the last human whose birth was officially recorded, unrelated as it was to any personal virtue or talent, had always been difficult for him to handle. And now he is dead. The news was given to us here in Britain on the nine o’clock programme of the State Radio Service and I heard it fortuitously. I had settled down to begin this diary of the last half of my life when I noticed the time and thought I might as well catch the headlines to the nine o’clock bulletin. Ricardo’s death was the last item mentioned, and then only briefly, a couple of sentences delivered without emphasis in the newscaster’s carefully non-committal voice. But it seemed to me, hearing it, that it was a small additional justification for beginning the diary today: the first day of a new year and my fiftieth birthday. As a child I had always liked that distinction, despite the inconvenience of having it follow Christmas too quickly so that one present—it never seemed notably superior to the one I would in any case have received—had to do for both celebrations.

As I begin writing, the three events, the New Year, my fiftieth birthday, Ricardo’s death, hardly justify sullying the first pages of this new loose-leaf notebook. But I shall continue, one small additional defence against personal accidie. If there is nothing to record, I shall record the nothingness and then if, and when, I reach old age—as most of us can expect to, we have become experts at prolonging life—I shall open one of my tins of hoarded matches and light my small personal bonfire of vanities. I have no intention of leaving the diary as a record of one man’s last years. Even in my most egotistical moods I am not as self-deceiving as that. What possible interest can there be in the journal of Theodore Faron, Doctor of Philosophy, Fellow of Merton College in the University of Oxford, historian of the Victorian age, divorced, childless, solitary, whose only claim to notice is that he is cousin to Xan Lyppiatt, the dictator and Warden of England. No additional personal record is, in any case, necessary. All over the world nation states are preparing to store their testimony for the posterity which we can still occasionally convince ourselves may follow us, those creatures from another planet who may land on this green wilderness and ask what kind of sentient life once inhabited it. We are storing our books and manuscripts, the great paintings, the musical scores and instruments, the artefacts. The world’s greatest libraries will in forty years’ time at most be darkened and sealed. The buildings, those that are still standing, will speak for themselves. The

soft stone of Oxford is unlikely to survive more than a couple of centuries. Already the University is arguing about whether it is worth refacing the crumbling Sheldonian. But I like to think of those mythical creatures landing in St. Peter’s Square and entering the great Basilica, silent and echoing under the centuries of dust. Will they realize that this was once the greatest of man’s temples to one of his many gods? Will they be curious about his nature, this deity who was worshipped with such pomp and splendour, intrigued by the mystery of his symbol, at once so simple, the two crossed sticks, ubiquitous in nature, yet laden with gold, gloriously jewelled and adorned? Or will their values and their thought processes be so alien to ours that nothing of awe or wonder will be able to touch them? But despite the discovery—in 1997, was it?—of a planet which the astronomers told us could support life, few of us really believe that they will come. They must be there. It is surely unreasonable to credit that only one small star in the immensity of the universe is capable of developing and supporting intelligent life. But we shall not get to them and they will not come to us.

Twenty years ago, when the world was already half-convinced that our species had lost for ever the power to reproduce, the search to find the last known human birth became a universal obsession, elevated to a matter of national pride, an international contest as ultimately pointless as it was fierce and acrimonious. To qualify, the birth had to be officially notified, the date and precise time recorded. This effectively excluded a high proportion of the human race where the day but not the hour was known, and it was accepted, but not emphasized, that the result could never be conclusive. Almost certainly, in some remote jungle, in some primitive hut, the last human being had slipped largely unnoticed into an unregarding world. But after months of checking and rechecking, Joseph Ricardo, of mixed race, born illegitimately in a Buenos Aires hospital at two minutes past three Western time on 19 October 1995, had been officially recognized. Once the result was proclaimed, he was left to exploit his celebrity as best he could while the world, as if suddenly aware of the futility of the exercise, turned its attention elsewhere. And now he is dead and I doubt whether any country will be eager to drag the other candidates from oblivion.

We are outraged and demoralized less by the impending end of our species, less even by our inability to prevent it, than by our failure to discover the cause. Western science and Western medicine haven’t prepared us for the magnitude and humiliation of this ultimate failure. There have been many diseases which have been difficult to diagnose or cure and one which almost depopulated two continents before it spent itself. But we have always in the end been able to explain why. We have given names to the viruses and germs which, even today, take possession of us, much to our chagrin since it seems a personal affront that they should still assail us, like old enemies who keep up the skirmish and bring down the occasional victim when their victory is assured. Western science has been our god. In the variety of its power it has preserved, comforted, healed, warmed, fed and entertained us and we have felt free to criticize and occasionally reject it as men have always rejected their gods, but in the knowledge that, despite our apostasy, this deity, our creature and our slave, would still provide for us; the anaesthetic for the pain, the spare heart, the new lung, the antibiotic, the moving wheels and the moving pictures. The light will always come on when we press the switch and if it doesn’t we can find out why. Science was never a subject I was at home with. I understood little of it at school and I understand little more now that I’m fifty. Yet it has been my god too, even if its achievements are incomprehensible to me, and I share the universal disillusionment of those whose god has died. I can clearly remember the confident words of one biologist spoken when it had finally become apparent that nowhere in the whole world was there a pregnant woman: “It may take us some time to discover the cause of this apparent universal infertility.” We have had twenty-five years and we no longer even expect to succeed. Like a lecherous stud suddenly stricken with impotence, we are humiliated at the very heart of our faith in ourselves. For all our knowledge, our intelligence, our power, we can no longer do what the animals do without thought. No wonder we both worship and resent them.

The year 1995 became known as Year Omega and the term is now universal. The great public debate in the late 1990s was whether the country which discovered a cure for the universal infertility would share this with the world and on what terms. It was accepted that this was a global disaster and that it must be met by the response of a united world. We still, in the late 1990s, spoke of Omega in terms of a disease, a malfunction which would in time be diagnosed and then corrected, as man had found a cure for tuberculosis, diphtheria, polio and even in the end, although too late, for AIDS. As the years passed and the united efforts under the aegis of the United Nations came to nothing, this resolve of complete openness fell apart. Research became secret, nations’ efforts a cause of fascinated, suspicious attention. The European Community acted in concert, pouring in research facilities and manpower. The European Centre for Human Fertility, outside Paris, was among the most prestigious in the world. This in turn co-operated, at least overtly, with the United States, whose efforts were if anything greater. But there was no inter-race co-operation; the prize was too great. The terms on which the secret might be shared were a cause of passionate speculation and debate. It was accepted that the cure, once found, would have to be shared; this was scientific knowledge which no race ought to, or could, keep to itself indefinitely. But across continents, national and racial boundaries, we watched each other suspiciously, obsessively, feeding on rumour and speculation. The old craft of spying returned. Old agents crawled out of comfortable retirement in Weybridge and Cheltenham and passed on their trade craft. Spying had, of course, never stopped, even after the official end of the Cold War in 1991. Man is too addicted to this intoxicating mixture of adolescent buccaneering and adult perfidy to relinquish it entirely. In the late 1990s the bureaucracy of espionage flourished as it hadn’t since the end of the Cold War, producing new heroes, new villains, new mythologies. In particular we watched Japan, half-fearing that this technically brilliant people might already be on the way to finding the answer.

Ten years on we still watch, but we watch with less anxiety and without hope. The spying still goes on but it is twenty-five years now since a human being was born and in our hearts few of us believe that the cry of a new-born child will ever be heard again on our planet. Our interest in sex is waning. Romantic and idealized love has taken over from crude carnal satisfaction despite the efforts of the Warden of England, through the national porn shops, to stimulate our flagging appetites. But we have our sensual substitutes; they are available to all on the National Health Service. Our ageing bodies are pummelled, stretched, stroked, caressed, anointed, scented. We are manicured and pedicured, measured and weighed. Lady Margaret Hall has become the massage centre for Oxford and here every Tuesday afternoon I lie on the couch and look out over the still-tended gardens, enjoying my State-provided, carefully measured hour of sensual pampering. And how assiduously, with what obsessive concern, do we intend to retain the illusion, if not of youth, of vigorous middle age. Golf is now the national game. If there had been no Omega, the conservationists would protest at the acres of countryside, some of it our most beautiful, which have been distorted and rearranged to provide ever more challenging courses. All are free; this is part of the Warden’s promised pleasure. Some have become exclusive, keeping unwelcome members out, not by prohibition, which is illegal, but by those subtle, discriminating signals which in Britain even the least sensitive are trained from childhood to interpret. We need our snobberies; equality is a political theory not a practical policy, even in Xan’s egalitarian Britain. I tried once to play golf but found the game immediately and totally unattractive, perhaps because of my ability to shift divots of earth, but never the ball. Now I run. Almost daily I pound the soft earth of Port Meadow or the deserted footpaths of Wytham Wood, counting the miles, subsequently measur

ing heartbeat, weight loss, stamina. I am just as anxious to stay alive as anyone else, just as obsessed with the functioning of my body.

Much of this I can trace to the early 1990s: the search for alternative medicine, the perfumed oils, the massage, the stroking and anointing, the crystal-holding, the non-penetrative sex. Pornography and sexual violence on film, on television, in books, in life, had increased and became more explicit but less and less in the West we made love and bred children. It seemed at the time a welcome development in a world grossly polluted by over-population. As a historian I see it as the beginning of the end.

We should have been warned in the early 1990s. As early as 1991 a European Community Report showed a slump in the number of children born in Europe—8.2 million in 1990, with particular drops in the Roman Catholic countries. We thought that we knew the reasons, that the fall was deliberate, a result of more liberal attitudes to birth control and abortion, the postponement of pregnancy by professional women pursuing their careers, the wish of families for a higher standard of living. And the fall in population was complicated by the spread of AIDS, particularly in Africa. Some European countries began to pursue a vigorous campaign to encourage the birth of children, but most of us thought the fall was desirable, even necessary. We were polluting the planet with our numbers; if we were breeding less it was to be welcomed. Most of the concern was less about a falling population than about the wish of nations to maintain their own people, their own culture, their own race, to breed sufficient young to maintain their economic structures. But as I remember it, no one suggested that the fertility of the human race was dramatically changing. When Omega came it came with dramatic suddenness and was received with incredulity. Overnight, it seemed, the human race had lost its power to breed. The discovery in July 1994 that even the frozen sperm stored for experiment and artificial insemination had lost its potency was a peculiar horror casting over Omega the pall of superstitious awe, of witchcraft, of divine intervention. The old gods reappeared, terrible in their power.

The Skull Beneath the Skin

The Skull Beneath the Skin A Taste for Death

A Taste for Death The Children of Men

The Children of Men The Part-Time Job

The Part-Time Job Death in Holy Orders

Death in Holy Orders The Victim

The Victim Shroud for a Nightingale

Shroud for a Nightingale Talking about Detective Fiction

Talking about Detective Fiction Sleep No More

Sleep No More The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories

The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories Time to Be in Earnest

Time to Be in Earnest Original Sin

Original Sin A Mind to Murder

A Mind to Murder Cover Her Face

Cover Her Face Innocent Blood

Innocent Blood Devices and Desires

Devices and Desires Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales

Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales Death Comes to Pemberley

Death Comes to Pemberley The Mistletoe Murder

The Mistletoe Murder Death of an Expert Witness

Death of an Expert Witness The Private Patient

The Private Patient The Black Tower

The Black Tower Devices & Desires - Dalgleish 08

Devices & Desires - Dalgleish 08 Unnatural Causes

Unnatural Causes An Unsuitable Job for a Woman

An Unsuitable Job for a Woman The Murder Room

The Murder Room A Certain Justice

A Certain Justice The Lighthouse

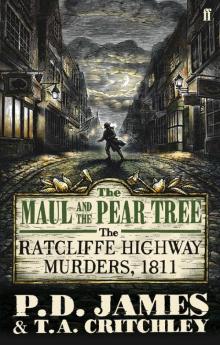

The Lighthouse The Maul and the Pear Tree

The Maul and the Pear Tree