- Home

- P. D. James

Unnatural Causes

Unnatural Causes Read online

Praise for P. D. James

“Her style is literate, her plots are complicated, her clues are abundant and fair and her solutions are intended to come as a surprise without straining credulity beyond that subtle point which is instinctively recognized and respected by addicts and practitioners alike.”

Times Literary Supplement

“The finest English crime novelist of her generation.”

The Globe and Mail

“P. D. James is one of the national treasures of British fiction. As James takes us from one life to another, her near-Dickensian scale becomes apparent.”

Sunday Mail

“P. D. James is unbeatable.”

Ottawa Citizen

“She is an addictive writer. P. D. James takes her place in the long line of those moralists who can tell a story as satisfying as it is complete.”

Anita Brookner

“P. D. James … writes the most lethal, erudite, people-complex novels of murder and detection since Michael Innes first began and Dorothy Sayers left us.”

Vogue

“P. D. James is a remarkable writer. Others have tried to rescue the detective story from its discredited position by freeing it from the bonds of the genre. But she has said that the discipline suits her, the restraints are a support and she can be a serious novelist within them. In this aim she has succeeded in a quite extraordinary way.”

Ruth Rendell

Also by P. D. James

Fiction

Cover Her Face

A Mind to Murder

Shroud for a Nightingale

An Unsuitable Job for a Woman

The Black Tower

Death of an Expert Witness

Innocent Blood

The Skull Beneath the Skin

A Taste for Death

Devices and Desires

The Children of Men

Original Sin

A Certain Justice

Death in Holy Orders

The Murder Room

The Lighthouse

The Private Patient

Non-fiction

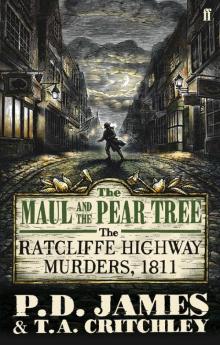

The Maul and the Pear Tree: The Ratcliffe Highway Murders, 1811 (with T. A. Critchley)

Time to Be in Earnest: A Fragment of Autobiography

Talking About Detective Fiction

CONTENTS

BOOK ONE

Suffolk

BOOK TWO

London

BOOK THREE

Suffolk

BOOK ONE

SUFFOLK

1

The corpse without hands lay in the bottom of a small sailing dinghy drifting just within sight of the Suffolk coast. It was the body of a middle-aged man, a dapper little cadaver, its shroud a dark pin-striped suit which fitted the narrow body as elegantly in death as it had in life. The handmade shoes still gleamed except for some scuffing of the toe caps, the silk tie was knotted under the prominent Adam’s apple. He had dressed with careful orthodoxy for the town, this hapless voyager; not for this lonely sea; nor for this death.

It was early afternoon in mid-October and the glazed eyes were turned upwards to a sky of surprising blue across which the light south-west wind was dragging a few torn rags of cloud. The wooden shell, without mast or rowlocks, bounced gently on the surge of the North Sea so that the head shifted and rolled as if in restless sleep. It had been an unremarkable face even in life, and death had given it nothing but a pitiful vacuity. The fair hair grew sparsely from a high, bumpy forehead; the nose was so narrow that the white ridge of bone looked as if it were about to pierce the flesh; the mouth, small and thin-lipped, had dropped open to reveal two prominent front teeth which gave the whole face the supercilious look of a dead hare.

The legs, still clamped in rigor, were wedged one each side of the centre-board case and the forearms had been placed resting on the thwart. Both hands had been taken off at the wrists. There had been little bleeding. On each forearm a trickle of blood had spun a black web between the stiff fair hairs and the thwart was stained as if it had been used as a chopping block. But that was all; the rest of the body and the boards of the dinghy were free of blood.

The right hand had been taken cleanly off and the curved end of the radius glistened white; but the left had been bungled and the jagged splinters of bone, needle sharp, stuck out from the receding flesh. Both jacket sleeves and shirt cuffs had been pulled up for the butchery and a pair of gold initialled cuff links dangled free, glinting as they slowly turned and were caught by the autumn sun.

The dinghy, its paintwork faded and peeling, drifted like a discarded toy on an almost empty sea. On the horizon the divided silhouette of a coaster was making her way down the Yarmouth Lanes; nothing else was in sight. About two o’clock a black dot swooped across the sky towards the land, trailing its feathered tail, and the air was torn by the scream of engines. Then the roar faded and there was again no sound but the sucking of the water against the boat and the occasional cry of a gull.

Suddenly the dinghy rocked violently, then steadied itself and swung slowly round. As if sensing the strong tug of the onshore current, it began to move more purposefully. A black-headed gull, which had dropped lightly onto the prow and had perched there, rigid as a figurehead, rose with wild cries to circle above the body. Slowly, inexorably, the water dancing at the prow, the little boat bore its dreadful cargo towards the shore.

2

Just before two o’clock on the afternoon of the same day Superintendent Adam Dalgliesh drove his Cooper Bristol gently onto the grass verge outside Blythburgh Church and, a minute later, passed through the north chantry-chapel door into the cold silvery whiteness of one of the loveliest church interiors in Suffolk. He was on his way to Monksmere Head just south of Dunwich to spend a ten-day autumn holiday with a spinster aunt, his only living relative, and this was his last stop on the way. He had started off from his City flat before London was stirring, and instead of taking the direct route to Monksmere through Ipswich, had struck north at Chelmsford to enter Suffolk at Sudbury. He had breakfasted at Long Melford and had then turned west through Lavenham to drive slowly and at will through the green and gold of this most unspoilt and unprettified of counties. His mood would have wholly matched the day if it weren’t for one persistent nagging worry. He had been deliberately putting off a personal decision until this holiday. Before he went back to London he must finally decide whether to ask Deborah Riscoe to marry him.

Irrationally, the decision would have been easier if he hadn’t known so certainly what her answer would be. This threw upon him the whole responsibility for deciding whether to change the present satisfactory status quo (well, satisfactory for him anyway, and it could be argued surely that Deborah was happier now than she had been a year ago?) for a commitment which both of them, he suspected, would regard as irrevocable no matter what the outcome. There are few couples as unhappy as those who are too proud to admit their unhappiness. Some of the hazards he knew. He knew that she disliked and resented his job. This wasn’t surprising nor, in itself, important. The job was his choice and he had never required anyone’s approval or encouragement. But it was a daunting prospect that every late duty, every emergency, might have to be preceded by an apologetic telephone call. As he walked to and fro under the marvellous cambered tie-beam roof and smelt the Anglican odour of wax polish, flowers and damp old hymn books, it came to him that he had got what he wanted at almost the precise moment of suspecting that he no longer wanted it. This experience is too common to cause an intelligent man lasting disappointment but it still has power to disconcert. It wasn’t the loss of freedom that deterred him; the men who squealed most about that were usually the least free. Much more difficult to face was the loss of privacy. Even the loss of physical privacy was hard to accept. Run

ning his fingers over the carved fifteenth-century lectern he tried to picture life in the Queenhithe flat with Deborah always there, no longer the eagerly awaited visitor but part of his life, the legal, certificated next of kin.

It had been a bad time at the Yard to be faced with personal problems. There had recently been a major reorganisation which had resulted in the inevitable disruption of loyalties and of routine, the expected crop of rumours and discontent. And there had been no relief from the pressure of work. Most of the senior officers were already working a fourteen-hour day. His last case, although successful, had been particularly tedious. A child had been murdered and the investigation had turned into a man hunt of the kind he most disliked and was temperamentally least suited for—a matter of dogged, persistent checking of facts carried on in a blaze of publicity and hindered by the fear and hysteria of the neighbourhood. The child’s parents had fastened on him like drowning swimmers gulping for reassurance and hope and he could still feel the almost physical load of their sorrow and guilt. He had been required to be at once a comforter and father-confessor, avenger and judge. There was nothing new to him in this. He had felt no personal involvement in their grief, and this detachment had, as always, been his strength, as the anger and intense, outraged commitment of some of his colleagues, faced with the same crime, would have been theirs. But the strain of the case was still with him and it would take more than the winds of a Suffolk autumn to clean his mind of some images. No reasonable woman could have expected him to propose marriage in the middle of this investigation and Deborah had not done so. That he had found time and energy to finish his second book of verse a few days before the arrest was something which neither of them had mentioned. He had been appalled to recognise that even the exercise of a minor talent could be made the excuse for selfishness and inertia. He hadn’t liked himself much recently, and it was perhaps sanguine to hope that this holiday could alter that.

Half an hour later he closed the church door quietly behind him and set off on the last few miles of the journey to Monksmere. He had written to his aunt to say that he would probably arrive at half past two and, with luck, he would be there almost precisely on time. If, as was usual, his aunt came out of the cottage at two-thirty she should see the Cooper Bristol just breasting the headland. He thought of her tall, angular, waiting figure with affection. There was little unusual about her story and most of it he had guessed, picked up as a boy from snatches of his mother’s unguarded talk or had simply known as one of the facts of his childhood. Her fiancé had been killed in 1918 just six months before the Armistice when she was a young girl. Her mother was a delicate, spoilt beauty, the worst possible wife for a scholarly country clergyman as she herself frequently admitted, apparently thinking that this candour both justified and excused in advance the next outbreak of selfishness or extravagance. She disliked the sight of other people’s grief since it rendered them temporarily more interesting than herself and she decided to take young Captain Maskell’s death very hard. Whatever her sensitive, uncommunicative and rather difficult daughter suffered it must be apparent that her mother suffered more; and three weeks after the telegram was received she died of influenza. It is doubtful whether she intended to go to such lengths but she would have been gratified by the result. Her distraught husband forgot in one night all the irritations and anxieties of his marriage and remembered only his wife’s gaiety and beauty. It was, of course, unthinkable that he should marry again, and he never did. Jane Dalgliesh, whose own bereavement hardly anyone now had the time to remember, took her mother’s place as hostess at the vicarage and remained with her father until his retirement in 1945 and his death ten years later. She was a highly intelligent woman and if she found unsatisfying the annual routine of housekeeping and parochial activities, predictable and inescapable as the liturgical year, she never said so. Her father was so assured of the ultimate importance of his calling that it never occurred to him that anyone’s gifts could be wasted in its service. Jane Dalgliesh, respected by the parishioners but never loved, did what had to be done and solaced herself with her study of birds. After her father’s death the papers she published, records of meticulous observation, brought her some notice; and in time what the parish had patronisingly described as “Miss Dalgliesh’s little hobby” made her one of the most respected of amateur ornithologists. Just over five years ago she had sold her house in Lincolnshire and bought Pentlands, a stone cottage on the edge of Monksmere Head. Here Dalgliesh visited her at least twice a year.

They were no mere duty visits, although he would have felt a responsibility for her if she were not so obviously self-sufficient that, at times, even to feel affection seemed a kind of insult. But the affection was there and both of them knew it. Already he was looking forward to the satisfaction of seeing her, to the assured pleasures of a holiday at Monksmere.

There would be a driftwood fire in the wide hearth scenting the whole cottage, and before it the high-backed armchair once part of his father’s study in the vicarage where he was born, the leather smelling of childhood. There would be a sparsely furnished bedroom with a view of sea and sky, a comfortable if narrow bed with sheets smelling faintly of woodsmoke and lavender, plenty of hot water and a bath long enough for a six-foot-two man to stretch himself in comfort. His aunt was herself six foot tall and had a masculine appreciation of essential comforts. More immediately, there would be tea before the fire and hot buttered toast with homemade potted meat. Best of all, there would be no corpses and no talk of them. He suspected that Jane Dalgliesh thought it odd that an intelligent man should choose to earn his living catching murderers and she was not a woman to feign polite interest when she felt none. She made no demands on him, not even the demands of affection, and because of this she was the only woman in the world with whom he was completely at peace. He knew exactly what the holiday offered. They would walk together, often in silence, on the damp strip of firm sand between the sea’s foam and the pebbled rises of the beach. He would carry her sketching paraphernalia, she would stride a little ahead, hands dug in her jacket pockets, eyes searching out where wheatears, scarcely distinguishable from pebbles, had lighted on the shingle, or following the flight of tern or plover. It would be peaceful, restful, utterly undemanding; but at the end of ten days he would go back to London with a sense of relief.

He was driving now through Dunwich Forest where the Forestry Commission’s plantations of dark firs flanked the road. He fancied that he could smell the sea now; the salt tang borne to him on the wind was sharper than the bitter smell of the trees. His heart lifted. He felt like a child coming home. And now the forest ended, the sombre dark green of the firs ruled off by a wire fence from the water-coloured fields and hedges. And now they too passed and he was driving through the gorse and heather of the heathlands on his way to Dunwich. As he reached the village and turned right up the hill which skirted the walled enclosure of the ruined Franciscan friory there was the blare of a car’s horn and a Jaguar, driven very fast, shot past. He glimpsed a dark head, and a hand raised in salute before, with a valedictory hoot, the car was out of sight. So Oliver Latham, the dramatic critic, was at his cottage for the weekend. That was hardly likely to inconvenience Dalgliesh for Latham did not come to Suffolk for company. Like his near neighbour, Justin Bryce, he used his cottage as a retreat from London, and perhaps from people, although he was at Monksmere less frequently than Bryce. Dalgliesh had met Latham once or twice and had recognised in him a restlessness and tension which found an echo in his own character. He was known to like fast cars and fast driving, and Dalgliesh suspected that it was in the drive to and from Monksmere that he found his release. It was difficult to imagine why else he kept on his cottage. He came to it seldom, never brought his women there, took no interest in furnishing it, and used it chiefly as a base for wild drives around the district which were so violent and irrational that they seemed a kind of abreaction.

As Rosemary Cottage came into sight on the bend of the road Dalgliesh acc

elerated. He had little hope of driving past unobserved but at least he could drive at a speed which made it unreasonable to stop. As he shot past he just had time to see out of the corner of his eye a face at an upstairs window. Well, it was to be expected. Celia Calthrop regarded herself as the doyenne of the small community at Monksmere and had assigned herself certain duties and privileges. If her neighbours were so ill-advised as not to keep her informed of the comings and goings of themselves and their visitors she was prepared to take some trouble to find out for herself. She had a quick ear for an approaching car and the situation of her cottage, just where the rough track across the headland joined the road from Dunwich, gave her every opportunity of keeping an eye on things.

Miss Calthrop had bought Brodie’s Barn, renamed Rosemary Cottage, twelve years previously. She had got it cheap and by gentle but persistent bullying of local labour, had converted it equally cheaply from a pleasing if shabby stone house to the romanticised ideal of her readers. It frequently featured in women’s magazines as “Celia Calthrop’s delightful Suffolk residence where, amid the peace of the countryside, she creates those delightful romances which so thrill our readers.” Inside, Rosemary Cottage was very comfortable in its pretentious and tasteless way; outside, it had everything its owner considered appropriate to a country cottage, a thatched roof (deplorably expensive to insure and maintain), a herb garden (a sinister looking patch this; Miss Calthrop was not successful with herbs), a small artificial pond (malodorous in summer) and a dovecote (but doves obstinately refused to roost in it). There was also a sleek lawn on which the “writers community”—Celia’s phrase—was invited in summer to drink tea. At first Jane Dalgliesh had been excluded from the invitations, not because she didn’t claim to be a writer but because she was a solitary, elderly spinster and therefore, in Miss Calthrop’s scale of values, a social and sexual failure rating only a patronising kindness. Then Miss Calthrop discovered that her neighbour was regarded as a distinguished woman by people well qualified to judge and that the men who, in defiance of propriety, were entertained at Pentlands and who were to be met trudging along the shore in happy companionship with their hostess were frequently themselves distinguished. A further discovery was more surprising. Jane Dalgliesh dined with R. B. Sinclair at Priory House. Not all those who praised Sinclair’s three great novels, the last written over thirty years ago, realised that he was still alive. Fewer still were invited to dine with him. Miss Calthrop was not a woman obstinately to persist in error and Miss Dalgliesh became “dear Jane” overnight. For her part she continued to call her neighbour “Miss Calthrop” and was as unaware of the rapprochement as she had been of the original disdain. Dalgliesh was never sure what she really thought of Celia. She seldom spoke about her neighbours and the women were too rarely in each other’s company for him to judge.

The Skull Beneath the Skin

The Skull Beneath the Skin A Taste for Death

A Taste for Death The Children of Men

The Children of Men The Part-Time Job

The Part-Time Job Death in Holy Orders

Death in Holy Orders The Victim

The Victim Shroud for a Nightingale

Shroud for a Nightingale Talking about Detective Fiction

Talking about Detective Fiction Sleep No More

Sleep No More The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories

The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories Time to Be in Earnest

Time to Be in Earnest Original Sin

Original Sin A Mind to Murder

A Mind to Murder Cover Her Face

Cover Her Face Innocent Blood

Innocent Blood Devices and Desires

Devices and Desires Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales

Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales Death Comes to Pemberley

Death Comes to Pemberley The Mistletoe Murder

The Mistletoe Murder Death of an Expert Witness

Death of an Expert Witness The Private Patient

The Private Patient The Black Tower

The Black Tower Devices & Desires - Dalgleish 08

Devices & Desires - Dalgleish 08 Unnatural Causes

Unnatural Causes An Unsuitable Job for a Woman

An Unsuitable Job for a Woman The Murder Room

The Murder Room A Certain Justice

A Certain Justice The Lighthouse

The Lighthouse The Maul and the Pear Tree

The Maul and the Pear Tree