- Home

- P. D. James

Innocent Blood

Innocent Blood Read online

Praise for Innocent Blood and P. D. James

“The drumbeaters are out for this novel and they should be. It’s a stunner.”

The Boston Globe

“Remarkable … could be read as a mainstream novel and a consider-able one. As a crime novel it is a peak of the art.”

The Times

“This quite remarkable novel lifts P. D. James to the ranks of the best novelists.… A tale of constant surprises and of mounting, sometimes harrowing suspense.”

The Wall Street Journal

“A novel clear and true. It is immensely readable, bright.… P. D. James is capable of handling her themes with astonishing clarity.”

The New York Times Book Review

“P. D. James … steps into territory occupied by Truman Capote, Shelby Foote, Carson McCullers, even Henry James.”

The New Republic

“A masterpiece … carefully crafted, beautifully written, and completely realized as a novel of suspense and contemporary manners.”

The Miami Herald

“A winner: a riveting drama and gripping tale.”

New York Post

“There are real surprises here, timed adroitly and written with fine economy.”

TIME

“Subtle, rich, allusive and positively Shakespearean.”

The New York Times

Also by P. D. James

Fiction

Cover Her Face

A Mind to Murder

Unnatural Causes

Shroud for a Nightingale

An Unsuitable Job for a Woman

The Black Tower

Death of an Expert Witness

The Skull Beneath the Skin

A Taste for Death

Devices and Desires

The Children of Men

Original Sin

A Certain Justice

Death in Holy Orders

The Murder Room

The Lighthouse

The Private Patient

Non-fiction

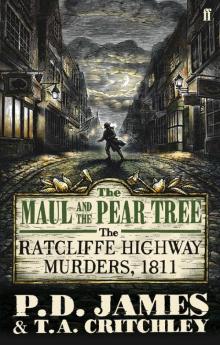

The Maul and the Pear Tree: The Ratcliffe Highway Murders, 1811 (with T. A. Critchley)

Time to Be in Earnest: A Fragment of Autobiography

Talking About Detective Fiction

VINTAGE CANADA EDITION, 2011

Copyright © 1980 P. D. James

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Published in Canada by Vintage Canada, a division of Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto, in 2011. Originally published in hardcover in Great Britain by Faber and Faber Ltd., London, in 1980. Distributed by Random House of Canada Limited.

Vintage Canada with colophon is a registered trademark.

www.randomhouse.ca

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

James, P. D., 1920–

Innocent blood / P. D. James.

eISBN: 978-0-307-40059-8

I. Title.

PR6060.A56I55 2011 823′.914 C00930386-3

v3.1

CONTENTS

Cover

Other Books by This Author

Title Page

Copyright

BOOK ONE

PROOF OF IDENTITY

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

BOOK TWO

AN ORDER OF RELEASE

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

BOOK THREE

ACT OF VIOLENCE

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

BOOK FOUR

EPILOGUE

About the Author

BOOK ONE

PROOF OF IDENTITY

1

The social worker was older than she had expected; perhaps the nameless official who arranged these matters thought that greying hair and menopausal plumpness might induce confidence in the adopted adults who came for their compulsory counselling. After all, they must be in need of reassurance of some kind, these displaced persons whose umbilical cord was a court order, or why had they troubled to travel this bureaucratic road to identity? The social worker smiled her encouraging professional smile. She said, holding out her hand: “My name is Naomi Henderson and you’re Miss Philippa Rose Palfrey. I’m afraid I have to begin by asking you for some proof of identity.”

Philippa nearly replied: “Philippa Rose Palfrey is what I’m called. I’m here to find out who I am,” but checked herself in time, sensing that such an affectation would be an unpropitious beginning to the interview. They both knew why she was here. And she wanted the session to be a success; wanted it to go her way without being precisely clear what way that was. She unclipped the fastening of her leather shoulder bag and handed over in silence her passport and the newly acquired driving licence.

The attempt at reassuring informality extended to the furnishing of the room. There was an official-looking desk, but Miss Henderson had moved from behind it as soon as Philippa was announced, and had motioned her to one of the two vinyl-covered armchairs on each side of a low table. There were even flowers on the table, a small blue bowl lettered “A present from Polperro.” It held a mixed bunch of roses. These weren’t the scentless, thornless buds of the florist’s window. These were garden roses, recognized from the garden at Caldecote Terrace: Peace, Superstar, Albertine, the blossoms overblown, already peeling with only one or two tightly furled buds, darkening at the lips and destined never to open. Philippa wondered if the social worker had brought them in from her own garden. Perhaps she was retired, living in the country, and had been recruited part-time for this particular job. She could picture her clumping round her rose bed in the brogues and serviceable tweeds she was wearing now, snipping away at roses which were due for culling, might just last out the London day. Someone had watered the flowers over-enthusiastically. A milky bead lay like a pearl between two yellow petals and there was a splash on the tabletop. But the imitation mahogany wouldn’t be stained; it wasn’t really wood. The roses gave forth a damp sweetness; but they weren’t really fresh. In these easy chairs no visitor had ever sat at ease. The smile which invited her confidence and trust across the table was bestowed by courtesy of section twenty-six of the Children Act 1975. She had taken trouble with her appearance, but then she always did, presenting herself to the world with self-conscious art, daily remaking herself in her own image. The aim this morning had been to suggest that no trouble had in fact been taken, that this interview had induced no special anxiety, warranted no exceptional care. Her stro

ng corn-coloured hair, bleached by the summer so that no two strands were exactly the same gold, was drawn back from a high forehead and knotted in a single heavy plait. The wide mouth with its strong, curved upper lip and sensuous droop at each corner was devoid of lipstick, but she had applied her eyeshadow with care, emphasizing her most remarkable feature, the luminous, slightly protuberant green eyes. Her honey-coloured skin glistened with sweat. She had lingered too long in the Embankment Gardens, unwilling to arrive early, and in the end had had to hurry. She wore sandals and a pale green open-necked cotton shirt above her corduroy trousers. In contrast to this casual informality, the careful ambiguity about money or social class, were the possessions which she wore like talismans: the slim gold watch, the three heavy Victorian rings, topaz, cornelian, peridot, the leather Italian bag slung from her left shoulder. The contrast was deliberate. The advantage of remembering virtually nothing before her eighth birthday, the knowledge that she was illegitimate, meant that there was no phalanx of the living dead, no pious ancestor worship, no conditioned reflexes of thought to inhibit the creativity with which she presented herself to the world. What she aimed to achieve was singularity, an impression of intelligence, a look that could be spectacular, even eccentric, but never ordinary.

Her file, clean and new, lay open before Miss Henderson. Across the table Philippa could recognize some of the contents: the orange and brown Government information sheet, a copy of which she had obtained from the Citizens’ Advice Bureau in north London where there had been no risk that she would be known or recognized; her letter to the Registrar General written five weeks ago, the day after her eighteenth birthday, in which she had requested the application form which was the first document to identity; a copy of the form itself. The letter was tagged on top of the file, stark white against the buff of bureaucracy. Miss Henderson fingered it. Something about it, the address, the quality of the heavy linen-based paper apparent even in a copy, evoked, Philippa thought, a transitory unease. Perhaps it was a recognition that her adoptive father was Maurice Palfrey. Given Maurice’s indefatigable self-advertisement, the stream of sociological publications which flowed from his department, it would be odd if a senior social worker hadn’t heard of him. She wondered whether Miss Henderson had read his Theory and Technique in Counselling: A Guide for Practitioners, and if so, how much she had been helped in bolstering her clients’ self-esteem—and what a significant word “client” was in social-work jargon—by Maurice’s lucid exploration of the difference between developmental counselling and gestalt therapy.

Miss Henderson said: “Perhaps I ought to begin by telling you how far I’m able to help you. Some of this you probably already know, but I find it useful to get it straight. The Children Act 1975 made important changes in the law relating to access to birth records. It provides that adopted adults, that is, people who are at least eighteen years old, may if they wish apply to the Registrar General for information which will lead them to the original record of their birth. When you were adopted you were given a new birth certificate, and the information which links your present name, Philippa Rose Palfrey, with your original birth certificate is kept by the Registrar General in confidential records. It is this linking information which the law now requires the Registrar General to give you if you want it. The 1975 Act also provides that anyone adopted before 12th November 1975, that is, before the Act was passed, must attend an interview with a counsellor before they can be given the information. The reason for this is that Parliament was concerned about making the new arrangements retrospective since over the years many natural parents gave up their children for adoption and adopters took on the children on the understanding that their natural parentage would remain unknown. So you have come here today so that we can consider together the possible effect of any inquiries you may make about your natural parents, both on yourself and on other people, and so that the information you are now seeking, and to which you have, of course, a legal right, is provided in a helpful and appropriate manner. At the end of our talk, and if you still want it, I shall be able to give you your original name, the name of your natural mother, possibly, but not certainly, the name of your natural father and the name of the court where your adoption order was made. I shall also be able to give you an application form which you can use to apply to the Registrar General for a copy of your original birth certificate.”

She had said it all before. It came out a little too pat.

Philippa said: “And there’s a standard charge of two pounds fifty pence for the birth certificate. It seems cheap at the price. I know all that. It’s in the orange and brown pamphlet.”

“As long as it’s quite clear. I wonder if you’d like to tell me when you first decided to ask for your birth record. I see that you applied as soon as you were eighteen. Was this a sudden decision or had you been thinking about it for some time?”

“I decided when the 1975 Act was passed. I was fifteen then and taking my O-levels. I don’t think I gave it a great deal of thought at the time. I just made up my mind that I’d apply as soon as I was legally able to.”

“Have you spoken to your adoptive parents about it?”

“No. We’re not exactly a communicative family.”

Miss Henderson let that pass for the moment.

“And what exactly did you have in mind? Do you want just to know who your natural parents are, or are you hoping to trace them?”

“I’m hoping to find out who I am. I don’t see the point of stopping at two names on a birth certificate. There may not even be two names. I know I’m illegitimate. The search may all come to nothing. I know that my mother is dead so I can’t trace her, and I may never find my father. But at least if I can find out who my mother was I may get a lead to him. He may be dead, too, but I don’t think so. Somehow I’m certain that my father is alive.”

Normally she liked her fantasies at least tenuously rooted in reality. Only this one was different, out of time, wildly improbable and yet impossible to relinquish, like an ancient religion whose archaic ceremonies, comfortingly familiar and absurd, somehow witness to an essential truth. She couldn’t remember why she had originally set her scene in the nineteenth century, or why, learning so soon that this was a nonsense since she had been born in 1960, she had never updated the persistent self-indulgent imaginings. Her mother, a slim figure dressed as a Victorian parlourmaid, an upswept glory of golden hair under the goffered cap with its two broderie anglaise streamers, ghost-like against the tall hedge which surrounded the rose garden. Her father in full evening dress striding like a god across the terrace, down the broad walk, under the spray of the fountains. The sloping lawn, drenched by the mellow light of the last sun, glittering with peacocks. The two shadows merging into one shadow, the dark head bending to the gold.

“My darling, my darling. I can’t let you go. Marry me.”

“I can’t. You know I can’t.”

It had become a habit to conjure up her favourite scenes in the minutes before she fell asleep. Sleep came in a drift of rose leaves. In the earliest dreams her father had been in uniform, scarlet and gold, his chest beribboned, sword clanking at his side. As she grew older she had edited out these embarrassing embellishments. The soldier, the fearless rider to hounds had become the aristocrat scholar. But the essential picture remained.

There was a globule of water creeping down the petal of the yellow rose. She watched it, fascinated, willing it not to fall. She had distanced her thoughts from what Miss Henderson had been saying. Now she made an effort to attend. The social worker was asking about her adoptive parents: “And your mother, what does she do?”

“My adoptive mother cooks.”

“You mean she works as a cook?” The social worker modified this as if conscious that it could imply some derogation, and added: “She cooks professionally?”

“She cooks for her husband and her guests and me. And she’s a juvenile court magistrate but I think she only took that on to please my adoptive father. He be

lieves that a woman should have a job outside the home, provided, of course, that it doesn’t interfere with his comfort. But cooking is her enthusiasm. She’s good enough at it to cook professionally, although I don’t think she was ever properly taught except at evening classes. She was my father’s secretary before they married. I mean that cooking is her hobby, her interest.”

“Well, that’s nice for your father and you.”

Presumably that hint of encouraging patronage was by now too unconsciously acquired to be easily disciplined. Philippa gazed at the woman stonily, noted it, took strength from it.

“Yes, we’re both greedy, my adoptive father and I. We can both eat voraciously without putting on weight.”

That, she supposed, implied something of an appetite for life, not indiscriminate since they were both appreciative of good food; perhaps a reinforcement of their belief that one could indulge without having to pay for indulgence. Greed, unlike sex, involved no commitment except to one’s self, no violence except to one’s own body. She had always taken comfort from her discernment about food and drink. That, at least, could hardly have been caught from his example. Even Maurice, convinced environmentalist that he was, would hardly claim that a nose for claret could be so easily acquired. Learning to enjoy wine, discovering that she had a palate, had been one more reassuring affirmation of inherited taste. She recalled her seventeenth birthday; the three bottles on the table before them, the labels shrouded. She couldn’t recall that Hilda had been with them. Surely she must have been present for a family birthday dinner, but in memory she and Maurice celebrated alone. He had said: “Now tell me which you prefer. Forget the purple prose of the colour supplements, I want to know what you think in your own words.”

She had tasted them again, holding the wine in her mouth, sipping water between each sampling since she supposed that this was the proper thing to do, watching his bright challenging eyes.

“This one.”

“Why?”

“I don’t know. I just like it best.”

The Skull Beneath the Skin

The Skull Beneath the Skin A Taste for Death

A Taste for Death The Children of Men

The Children of Men The Part-Time Job

The Part-Time Job Death in Holy Orders

Death in Holy Orders The Victim

The Victim Shroud for a Nightingale

Shroud for a Nightingale Talking about Detective Fiction

Talking about Detective Fiction Sleep No More

Sleep No More The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories

The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories Time to Be in Earnest

Time to Be in Earnest Original Sin

Original Sin A Mind to Murder

A Mind to Murder Cover Her Face

Cover Her Face Innocent Blood

Innocent Blood Devices and Desires

Devices and Desires Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales

Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales Death Comes to Pemberley

Death Comes to Pemberley The Mistletoe Murder

The Mistletoe Murder Death of an Expert Witness

Death of an Expert Witness The Private Patient

The Private Patient The Black Tower

The Black Tower Devices & Desires - Dalgleish 08

Devices & Desires - Dalgleish 08 Unnatural Causes

Unnatural Causes An Unsuitable Job for a Woman

An Unsuitable Job for a Woman The Murder Room

The Murder Room A Certain Justice

A Certain Justice The Lighthouse

The Lighthouse The Maul and the Pear Tree

The Maul and the Pear Tree