- Home

- P. D. James

Unnatural Causes Page 14

Unnatural Causes Read online

Page 14

Dalgliesh, although he was not a member of the club, had occasionally dined there and was known to Plant. Luckily, too, by that curious alchemy which operates in these matters, he was approved of. Plant made no difficulties about showing him round or answering his questions; nor was it necessary for Dalgliesh to emphasise his present amateur status. Very little was said but both men understood each other perfectly. Plant led the way to the small front bedroom on the first floor which Seton had always used and waited just inside the door while Dalgliesh examined the room. Dalgliesh was used to working under scrutiny or he might have been disconcerted by the man’s stolid watchfulness. Plant was an arresting figure. He was six feet three inches tall, and broad shouldered, his face pale and pliable as putty with a thin scar sliced diagonally across his left cheekbone. This mark, the result of an undignified tumble from a bicycle onto iron railings in his youth, looked so remarkably like a duelling scar that Plant had been unable to resist adding to its effect by wearing a pince-nez and cropping his hair en brosse, like a sinister Commander in an anti-Nazi film. His working uniform was appropriate, a dark blue serge with a miniature skull on each lapel; this vulgar conceit, introduced in 1896 by the club’s founder, had now, like Plant himself, been sanctified by time and custom. Indeed, members were always a little puzzled when their visitors commented on Plant’s unusual appearance.

There was little to be seen in the bedroom. Thin terylene curtains were drawn against the grey light of the October afternoon. The drawers and wardrobe were empty. The small desk of light oak in front of the window held nothing but a clean blotter and a supply of club writing paper. The single bed, freshly made up, awaited its next occupant.

Plant said: “The officers from the Suffolk CID took away his typewriter and clothes, Sir. They looked for papers, too, but he hadn’t any to speak of. There was a packet of buff envelopes and about fifty sheets of foolscap and a sheet or two of unused carbon paper but that’s all. He was a very tidy gentleman, Sir.”

“He stayed here regularly every October didn’t he?”

“The last two weeks in the month, Sir. Every year. And he always had this room. We’ve only got the one bedroom on this floor and he couldn’t climb stairs because of his bad heart. Of course, he could have used the lift but he said he hadn’t any confidence in lifts. So it had to be this room.”

“Did he work in here?”

“Yes, Sir. Most mornings from ten until half past twelve. That’s when he lunched. And again from two-thirty until half past four. That’s if he was typing. If it was a matter of reading or making notes he worked in the library. But there’s no typing allowed in the library on account of disturbing other members.”

“Did you hear him typing in here on Tuesday?”

“The wife and I heard someone typing, Sir, and naturally we thought it was Mr. Seton. There was a notice on the door saying not to disturb but we wouldn’t have come in anyway. Not when a member’s working. The Inspector seemed to think it might have been someone else in here.”

“Did he now? What do you think?”

“Well, it could have been. The wife heard the typewriter going at about eleven o’clock in the morning and I heard it again at about four. But we wouldn’t either of us know whether it was Mr. Seton. It sounded pretty quick and expert-like but what’s that to go on? That Inspector asked whether anyone else could have got in. We didn’t see any strangers about but we were both busy at lunchtime and downstairs most of the afternoon. People walk in and out very freely, Sir, as you know. Mind you, a lady would have been noticed. One of the members would have mentioned it if there’d been a lady about the club. But otherwise—well, I couldn’t pretend to the Inspector that the place is what he’d call well supervised. He didn’t seem to think much of our security arrangements. But, as I told him Sir, this is a club not a police station.”

“You waited two nights before you reported his disappearance?”

“More’s the pity, Sir. And even then, I didn’t call the police. I phoned his home and gave a message to his secretary, Miss Kedge. She said to do nothing for the moment and she would try to find Mr. Seton’s half-brother. I’ve never met the gentleman myself but I think Mr. Maurice Seton did mention him to me once. But he’s never been to the club that I remember. That Inspector asked me particularly.”

“I expect he asked about Mr. Oliver Latham and Mr. Justin Bryce too.”

“He did, Sir. They’re both members and so I told him. But I haven’t seen either gentleman recently and I don’t think they’d come and go without a word to me or the wife. You’ll want to see this first-floor bathroom and lavatory. Here we are. Mr. Seton used this little suite. That Inspector looked in the cistern.”

“Did he indeed? I hope he found what he was looking for.”

“He found the ballcock, Sir and I hope to God he hasn’t put it out of action. Very temperamental this lavatory is. You’ll want to see the library, I expect. That’s where Mr. Seton used to sit when he wasn’t typing. It’s on the next floor as I think you know.”

A visit to the library was obviously scheduled. Inspector Reckless had been thorough and Plant was not the man to let his protegé get away with less. As they crushed together into the tiny claustrophobic lift, Dalgliesh asked his last few questions. Plant replied that neither he nor any member of his staff had posted anything for Mr. Seton. No one had tidied his room or destroyed any papers. As far as Plant knew there had been none to destroy. Except for the typewriter and Seton’s clothes, the room was still as he had left it on the evening he disappeared.

The library, which faced south over the square, was probably the most attractive room in the house. It had originally been the drawing room and, except for the provision of shelves along the whole of the west wall, looked much as it had when the club took over the house. The curtains were copies of the originals, the wallpaper was a faded Pre-Raphaelite design, the desks set between the four high windows were Victorian. The books made up a small but reasonably comprehensive library of crime. There were the notable British Trials and Famous Trials series; textbooks on medical jurisprudence, toxicology and forensic pathology; memoirs of judges, advocates, pathologists and police officers; a variety of books by amateur criminologists dealing with some of the more notable or controversial murders; textbooks on criminal law and police procedure; and even a few treatises on the sociological and psychological aspects of violent crime which showed few signs of having been opened. On the fiction shelves a small section held the club’s few first editions of Poe, Le Fanu and Conan Doyle; for the rest, most British and American crime writers were represented and it was apparent that those who were members presented copies of their books. Dalgliesh was interested to see that Maurice Seton had had his specially bound and embellished with his monogram in gold. He also noted that, although the club excluded women from membership, the ban did not extend to their books, so that the library was fairly representative of crime writing during the last 150 years.

At the opposite end of the room stood a couple of showcases containing what was, in effect, a small museum of murder. As the exhibits had been given or bequeathed by members over the years and accepted in the same spirit of uncritical benevolence they varied as greatly in interest as, Dalgliesh suspected, in authenticity. There had been no attempt at chronological classification and little at accurate labelling and the objects had been placed in the showcases with more apparent care for the general artistic effect than for logical arrangement. There was a flintlock duelling pistol, silver-mounted and with gold-lined flashpans, which was labelled as the weapon used by the Rev. James Hackman, executed at Tyburn in 1779 for the murder of Margaret Reay, mistress of the Earl of Sandwich. Dalgliesh thought it unlikely. He judged that the pistol was made some fifteen years later. But he could believe that the glittering and beautiful thing had an evil history. There was no need to doubt the authenticity of the next exhibit, a letter, brown and brittle with age from Mary Blandy to her lover thanking him for the gift of “powder to

clean the Scotch pebbles”—the arsenic which was to kill her father and bring her to the scaffold. In the same case a Bible with the signature “Constance Kent” on the flyleaf, a tattered rag of pyjama jacket said to have formed part of the wrapping around Mrs. Crippen’s body, a small cotton glove labelled as belonging to Madeline Smith and a phial of white powder, “arsenic found in the possession of Major Herbert Armstrong.” If the stuff were genuine there was enough there to cause havoc in the dining room, and the showcases were unlocked.

But when Dalgliesh voiced his concern Plant smiled: “That’s not arsenic, Sir. Sir Charles Winkworth said just the same as yourself about nine months ago. ‘Plant,’ he said, ‘if that stuff’s arsenic we must get rid of it or lock it up.’ So we took a sample and sent it off to be analysed on the quiet. It’s bicarbonate of soda, Sir, that’s what it is. I’m not saying it didn’t come from Major Armstrong and I’m not denying it wasn’t bicarb that killed his wife. But that stuff’s harmless. We left it there and said nothing. After all, it’s been arsenic for the last thirty years and it might as well go on being arsenic. As Sir Charles said, start looking at the exhibits too closely and we’ll have no museum left. And now, Sir, if you’ll excuse me I think I ought to be in the dining room. That is, unless there’s anything else I can show you.”

Dalgliesh thanked him and let him go. But he lingered himself for a few more minutes in the library. He had a tantalising and irrational feeling that somewhere, and very recently, he had seen a clue to Seton’s death, a fugitive hint which his subconscious mind had registered but which obstinately refused to come forward and be recognised. This experience was not new to him. Like every good detective, he had known it before. Occasionally it had led him to one of those seemingly intuitive successes on which his reputation partly rested. More often the transitory impression, remembered and analysed, had been found irrelevant. But the subconscious could not be forced. The clue, if clue it were, for the moment eluded him. And now the clock above the fireplace was striking one. His host would be waiting for him.

There was a thin fire in the dining room, its flame hardly visible in the shaft of autumn sunlight which fell obliquely across tables and carpet. It was a plain, comfortable room, reserved for the serious purpose of eating, the solid tables well spaced, flowerless, the linen glistening white. There was a series of original “Phiz” drawings for the illustrations to Martin Chuzzlewit on the walls for no good reason except that a prominent member had recently given them. They were, Dalgliesh thought, an agreeable substitute for the series of scenes from old Tyburn which had previously adorned the room but which he suspected the Committee, tenacious of the past, had taken down with some regret.

Only one main dish is served at luncheon or dinner at the Cadaver Club, Mrs. Plant holding the view that, with a limited staff, perfection is incompatible with variety. There is always a salad and cold meats as alternative and those who fancy neither this nor the main dish are welcome to try if they can do better elsewhere. Today, as the menu on the library notice board had proclaimed, they were to have melon, steak and kidney pudding, and lemon soufflé. Already the first puddings, napkin swathed, were being borne in.

Max Gurney was waiting for him at a corner table, conferring with Plant about the wine. He raised a plump hand in episcopal salute which gave the impression both of greeting his guest and of bestowing a blessing on the lunches generally. Dalgliesh felt immediately glad to see him. This was the emotion which Max Gurney invariably provoked. He was a man whose company was seldom unwelcome. Urbane, civilised and generous, he had an enjoyment of life and of people which was infectious and sustaining. He was a big man who yet gave an impression of lightness, bouncing along on small, high-arched feet, hands fluttering, eyes black and bright behind the immense horn-rimmed spectacles. He beamed at Dalgliesh.

“Adam! This is delightful. Plant and I have agreed that the Johannisberger Auslese 1959 would be very pleasant, unless you have a fancy for something lighter. Good. I do dislike discussing wine longer than I need. It makes me feel I’m behaving too like the Hon. Martin Carruthers.”

This was a new light on Seton’s detective. Dalgliesh said that he hadn’t realised that Seton understood wine.

“Nor did he, poor Maurice. He didn’t even care for it greatly. He had an idea that it was bad for his heart. No, he got all the details from books. Which meant, of course, that Carruthers’ taste was deplorably orthodox. You are looking very well, Adam. I was afraid that I might find you slightly deranged under the strain of having to watch someone else’s investigation.”

Dalgliesh replied gravely that he had suffered more in pride than in health but that the strain was considerable. Luncheon with Max would, as always, be a solace.

Nothing more was said about Seton’s death for twenty minutes. Both were engaged with the business of eating. But when the pudding had been served and the wine poured Max said: “Now, Adam, this business of Maurice Seton. I may say I heard of his death with a sense of shock and”—he selected a succulent piece of beef and speared it to a button mushroom and half a kidney—”outrage. And so, of course, have the rest of the firm. We do not expect to lose our authors in such a spectacular way.”

“Good for sales, though?” suggested Dalgliesh mischievously.

“Oh no! Not really, dear boy. That is a common misconception. Even if Seton’s death were a publicity stunt, which, admit it, would suggest somewhat excessive zeal on poor Maurice’s part, I doubt whether it would sell a single extra copy. A few dozen old ladies will add his last book to their library lists but that isn’t quite the same thing. Have you read his latest, by the way? One for the Pot, an arsenic killing set in a pottery works. He spent three weeks last April learning to throw pots before he wrote it, so conscientious always. But no, I suppose you wouldn’t read detective fiction.”

“I’m not being superior,” said Dalgliesh. “You can put it down to envy. I resent the way in which fictional detectives can arrest their man and get a full confession gratis on evidence which wouldn’t justify me in applying for a warrant. I wish real-life murderers panicked that easily. There’s also the little matter that no fictional detective seems to have heard of the Judge’s Rules.”

“Oh, the Honourable Martin is a perfect gentleman. You could learn a lot from him, I’m sure. Always ready with the apt quotation and a devil with the women. All perfectly respectable of course but you can see that the female suspects are panting to leap into bed with the Hon. if only Seton would let them. Poor Maurice! There was a certain amount of wishfulfilment there I think.”

“What about his style?” asked Dalgliesh, who was beginning to think that his reading had been unnecessarily restricted.

“Turgid but grammatical. And, in these days, when every illiterate debutante thinks she is a novelist, who am I to quarrel with that? Written I imagine with Fowler on his left hand and Roget on his right. Stale, flat and, alas, rapidly becoming unprofitable. I didn’t want to take him on when he left Maxwell Dawson five years ago but I was outvoted. He was almost written out then. But we’ve always had one or two crime novelists on the list and we bought him. Both parties regretted it, I think, but we hadn’t yet come to the parting of the ways.”

“What was he like as a person?” asked Dalgliesh.

“Oh, difficult. Very difficult, poor fellow! I thought you knew him? A precise, self-opinionated, nervous little man perpetually fretting about his sales, his publicity or his book jackets. He overvalued his own talent and undervalued everyone else’s, which didn’t exactly make for popularity.”

“A typical writer, in fact?” suggested Dalgliesh mischievously.

“Now Adam, that’s naughty. Coming from a writer, it’s treason. You know perfectly well that our people are as hard-working, agreeable and talented a bunch as you’ll find outside any mental hospital. No, he wasn’t typical. He was more unhappy and insecure than most. I felt sorry for him occasionally but that charitable impulse seldom survived ten minutes in his company.”

“Yes, he did. When I last saw him about ten weeks ago. I had to listen to the usual diatribe about the decline of standards and the exploitation of sex and sadism but then he told me that he was planning to write a thriller himself. In theory, of course, I should have welcomed the change, but, in fact, I couldn’t quite see him pulling it off. He hadn’t the jargon or the expertise. It’s a highly professional game and Seton was lost when he went outside his own experience.”

“Surely that was a grave handicap for a detective writer?”

“Oh, he didn’t actually do murder as far as I know. At least, not in the service of his writing. But he kept to familiar characters and settings. You know the kind of thing. Cosy English village or small-town scene. Local characters moving on the chessboard strictly according to rank and station. The comforting illusion that violence is exceptional, that all policemen are honest, that the English class system hasn’t changed in the last twenty years and that murderers aren’t gentlemen. He was absolutely meticulous about detail though. He never described a murder by shooting, for example, because he couldn’t understand firearms. But he was very sound on toxicology and his forensic medical knowledge was considerable. He took a great deal of trouble with rigor mortis and details like that. It peeved him when the reviewers didn’t notice it and the readers didn’t care.”

The Skull Beneath the Skin

The Skull Beneath the Skin A Taste for Death

A Taste for Death The Children of Men

The Children of Men The Part-Time Job

The Part-Time Job Death in Holy Orders

Death in Holy Orders The Victim

The Victim Shroud for a Nightingale

Shroud for a Nightingale Talking about Detective Fiction

Talking about Detective Fiction Sleep No More

Sleep No More The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories

The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories Time to Be in Earnest

Time to Be in Earnest Original Sin

Original Sin A Mind to Murder

A Mind to Murder Cover Her Face

Cover Her Face Innocent Blood

Innocent Blood Devices and Desires

Devices and Desires Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales

Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales Death Comes to Pemberley

Death Comes to Pemberley The Mistletoe Murder

The Mistletoe Murder Death of an Expert Witness

Death of an Expert Witness The Private Patient

The Private Patient The Black Tower

The Black Tower Devices & Desires - Dalgleish 08

Devices & Desires - Dalgleish 08 Unnatural Causes

Unnatural Causes An Unsuitable Job for a Woman

An Unsuitable Job for a Woman The Murder Room

The Murder Room A Certain Justice

A Certain Justice The Lighthouse

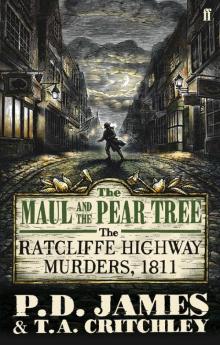

The Lighthouse The Maul and the Pear Tree

The Maul and the Pear Tree