- Home

- P. D. James

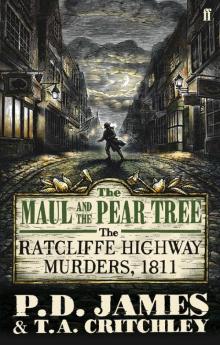

The Maul and the Pear Tree Page 15

The Maul and the Pear Tree Read online

Page 15

SEVEN

Verdict from Shadwell

Next morning the three magistrates took their seats early on the raised dais under the Royal Arms. The court was already crowded. The seats, like boxed-in church pews, which were reserved for important visitors, were crammed to capacity; in the well of the court a packed mass of humanity moved restlessly, as yet another spectator edged himself into the crush. It was clear that this interrogation of Williams would be vital, that a large number of witnesses had been summoned, and were now waiting to be called. All the exhibits had been assembled, and the blood-stained maul and the three chisels (or was one an iron crow?) prominently displayed.

Outside the Public Office the mob stamped their feet on cobbles white with a first sprinkling of winter snow, eager for the arrival of the coach which would bring John Williams from Coldbath Fields Prison. Inside, those nearest the door strained their ears for the sound of wheels. The magistrates whispered softly together. It was already past the hour when the prisoner was due to arrive.

But when, at last, the court heard the subdued buzz of excitement which heralded an arrival, and the door finally opened, it revealed not the expected figure of Williams, ironed and manacled, but a solitary police officer. He marched up to the magistrates and delivered his news. The prisoner was dead, and by his own hand. When the exclamations of surprise and disappointment had died down the magistrates demanded details. They were soon given. The discovery had been made when the turnkey went to Williams’s cell to prepare him for his appearance before the bench. He found the prisoner suspended by the neck from an iron bar which crossed the cell, and on which the inmate could hang his clothes. The body was quite cold and lifeless. The coat and shoes were off. There had been no warning. Williams had appeared tolerably cheerful when the turnkey had locked his cell the previous night, and had spoken with confidence of his hope of a speedy release.

The magistrates softly conferred together above the hum of speculation from the court. Their decision was quickly reached. The interrogations would proceed. There was no pretence now that this was a disinterested investigation. Williams had pronounced sentence on himself. The day’s business would be to hear the evidence which would formally confirm his guilt. As The Times put it next day, ‘The magistrates proceeded to examine the evidence on which they intended to found his final commitment.’

Mrs Vermilloe, the landlady of the Pear Tree, and obviously a key witness, was called first. On Tuesday she had broken down on being shown the maul, and had been unable positively to identify it as having been in Peterson’s chest. Then, on Christmas Day, she had given ‘decisive information’ as to its identity. On that occasion, however, she had been interviewed privately in Newgate Prison with her husband. Clearly it was desirable that she should affirm the maul’s identity in public. But now, away from her husband’s influence, she again equivocated. The London Chronicle reported:

Mrs Vermilloe was very closely questioned by the Magistrates as to her knowledge of the fatal maul, which she declared she never missed until Monday last. She could not be at all positive that it was one of those which belonged to John Peterson. She seemed unwilling to identify it, and was asked by the magistrates whether, when she heard her husband in Newgate stated it to be the same, she had not exclaimed, ‘Good God, why does he say so?’ She at first denied using the expression, but on a witness being called who overheard her, she confessed that she employed it, or something like it.

Was Mrs Vermilloe simply terrified? Had she been threatened? Or had she something to hide? It was important to know when she had first had suspicions of Williams, and what aroused them:

The first time she had any suspicion that Williams was concerned in either of the murders was when a young man named Harris [sic] who slept with Williams, showed her a pair of stockings belonging to him, which had been tucked behind a trunk in an extremely muddy state, even to within about an inch of the top. On further examination of them she saw evidently the marks of two bloody fingers upon the top of one of them. She then called in a man named Glass to look at them. He, believing the stains to be those of blood, advised Mrs Vermilloe to turn Williams out of the house.

This news created something of a sensation. Why had she not disclosed so important a matter on her first examination? the magistrates demanded. The witness hesitated. Had she been intimidated by Williams?

She admitted that she was afraid that he, or some of his acquaintances, would murder her.

Q. You need now have no such fear. You know his situation. You have heard that he has hanged himself?

(Much affected and shocked) Good God! I hope not.

Q. Why do you hope not?

(After hesitation) I should have been sorry, if he was innocent, that he should have suffered.

What did Mrs Vermilloe know? What was she holding back? She was probably not an intelligent woman and was obviously much under her husband’s influence. He had impressed upon her the importance of saying nothing which might jeopardise their chance of reward. Besides, she wanted to oblige the gentlemen by telling them what they wanted to hear – if only she could be sure what it was. She wanted, too, to protect the reputation of her house, even in front of those who might not have agreed that it had a reputation worth preserving. One thing was now clear to her. John Williams was dead. Nothing she could say or conceal could help him now. And so, in her ignorance and fear, confused by repeated questioning and often on the verge of hysteria, she hesitated, prevaricated, and made confusion worse. The magistrates pressed her yet again about her first suspicion about Williams, and now she told a different story. It was not, after all, Harrison’s discovery of some muddy stockings.

The discovery of the maul marked ‘J.P.’ was the first thing that made her suspect Williams of the murder of Mr Marr’s family. The witness then related the circumstances of the discovery beforementioned of the ripping iron, at Mrs Orr’s window, which somewhat confirmed her suspicions.

The questions then put referred to the connections and associates of Williams, to which she replied that he had none, excepting now and then a few shipmates. He was in the habit of going to all the public houses, and behaving with great familiarity, but she never knew that he had any friends. When he returned from the East Indies, in the Roxburgh Castle, three months ago, he deposited £30 in her husband’s hands, which was not all expended at the time of the murders.

The stockings and shoes Williams is supposed to have worn on the night of the murder of Williamson were now produced. The stockings appeared to have been washed, but the stains of blood had not quite disappeared. The shoes had likewise been washed.

Williams was in the habit of wearing very large whiskers, and Saturday night last was the first time she perceived that he had cut them off. After this period she closely watched him, and she thought he seemed to be afraid to look at her. The subject of the two murders was often mentioned in his company, and though before very talkative, she observed that Williams always slunk out of the way into the passage, and seemed to be listening to what was said. One day it was remarked to him that Williamson’s murder was a very shocking affair. – ‘Yes,’ he said ‘very shocking,’ and he then turned off the conversation.

The witness was opening up, more at her ease. So the magistrates made yet another attempt to get her to identify the maul:

The maul, the ripping iron, and the two chisels were now brought before the witness that she might, if possible, identify them. But she shrunk away from the fatal instrument in horror. All she could say was that she had seen a maul something like it in her husband’s house.

The magistrates tried another line:

Q. How long has Williams been at home?

About twelve weeks. He came home on 2nd. October.

Q. Have you ever heard of the circumstances of a Portuguese being stabbed at the end of Old Gravel Lane between two and three months ago?

Yes.

Q. Was Williams at home at this time?

He was.

Q.

Did you hear anyone say that Williams was concerned in stabbing this man?

I can’t positively say I did.

Anything, it seems, was now good enough to blacken the character of the dead man, but they could get little out of Mrs Vermilloe on that score. She did, however, offer three more points that might be material to the case:

Since the arrest of Williams, a carpenter, of the name of Trotter, had called to enquire after him, and said he would soon be cleared. On the night of the last murder Williams had told the witness that Williamson was going the next day to pay his brewer. Williams’s name, she had heard, was John Murphy.

Mrs Vermilloe stood down and was followed into the witness box by Robert Lawrence, the licensee of one of Williams’s favourite public houses, the Ship and Royal Oak. He said that Williams used to sit at the bar with great familiarity, but he never cared for the man. His daughter, however, knew Williams well. The girl, a ‘very interesting female’ according to an impressionable Morning Post journalist, was duly called:

She knew Williams before Marr’s murder. He gained her good opinion. After Marr’s murder he used to say, ‘Miss Lawrence, I don’t know what is the matter with me. I feel so uneasy.’ Once he came into the house greatly agitated, and said – ‘I don’t think I’m well, for I am unhappy and can’t remain easy.’ Miss Lawrence answered, ‘Williams, you ought to know best what you have done.’ He replied, ‘Why, last night I ate a good supper off fowls, and had plenty of liquor.’ Miss Lawrence immediately said, ‘Good eating is not the way to make you unhappy,’ on which he retired.

Miss Lawrence had been serving behind the bar when the scuffle broke out between Williams and the Irish coal-heavers, which accounted, according to Williams, for one of the torn and bloody shirts that Mrs Rice had washed. The Times reported:

On Friday week in the evening he came into their house with his coat off and said he wanted to find the police officers. He was then very tipsy. Some people in the taproom began to play tricks with him. A snuff box was handed around with some coal ashes mixed among the snuff, of which he partook when it was given to him. He was going to strike the person who gave it to him, but was prevented by somebody’s interposition. There was no fighting, nor was Williams struck. Nor was his mouth cut as he had represented for the purpose of accounting for the blood on his shirt. He was taken away, but returned half an hour afterwards and behaved very peacefully. Witness had not seen Williams since Saturday week, when she desired him not to come again to their house.

Williams’s explanation that his shirt had become torn and bloodied in a pub brawl clearly referred to the shirt which Mrs Rice testified she had washed before the Marrs’ murders. He was apparently unable to account, when asked, for the state of the second shirt, probably because, on the washerwoman’s evidence, it was far less extensively bloodied. Miss Lawrence’s testimony was intended to prove Williams a liar by discrediting an explanation which he had not, in fact given. It is probable, however, that by the end of her evidence no one in court, including the magistrates, was clear about which particular bloodied shirt was now in question.

And so, gradually, the prejudice against Williams was building up, despite the confusion and inconsistency of much of the testimony. Now came another key witness – John Harrison, the sailmaker, who had shared Williams’s bedroom at the Pear Tree:

He stated that he never saw anybody in company with Williams but the carpenter (Hart). He had heard that this was the same man who had been working at Mr Marr’s house. Williams came to the house at about half past twelve on the night Mr Marr and family were murdered. In the morning when witness heard of it, he told Mrs Vermilloe, the landlady. He then went upstairs to Williams and told him also. Williams replied in a surly manner, ‘I know it.’ He was then in bed and had not been out that morning. Witness said he might possibly have overheard him telling Mrs Vermilloe. That morning Williams walked out by himself. Witness had been reading the newspaper containing an account of the murder of Mr Marr, and when he found the muddy stockings behind the chest something like suspicion struck him. He brought the stockings downstairs and showed them to Mrs Vermilloe and several other people. From this circumstance and from the general conduct of Williams he was thoroughly persuaded he was concerned in the murder. He had told witness that he was well acquainted with Mr Marr. One day he was walking from the City with Williams. He said that Mr Marr had money to a considerable amount.

When he showed him the muddied stockings he took them into the backyard and washed them, at first in a rough manner in cold water; and when witness afterwards saw them they were quite clean. As witness slept in the same room he had an opportunity of observing his conduct since the murders. As he strongly suspected he was concerned in them, he longed for an opportunity of searching his clothes for some marks of blood. He was, however, always baffled in his intentions for whenever he attempted to approach his bed he found him awake. He always seemed restless, continually turning about in his bed and much agitated. He had overheard him speaking in his sleep. One night since the murder he heard him saying in his sleep, ‘Five shillings in my pocket – my pocket’s full of silver.’ Witness called out to him repeatedly, ‘What is the matter with you and what do you mean?’ but he got no answer from him. When he slept he did not seem to be soundly asleep but always disturbed. In the morning after the murder of Williamson he saw a pair of muddy shoes under Williams’s bed. Witness had always an impression on his mind against the prisoner, and always wished for an opportunity of bringing forward some evidence against him.

Williams’s other room-mate, John Cuthperson, told a similar story. On the Thursday before the Williamsons were murdered, he said, Williams had no money, and next morning he had a good deal. Williams was restless at night, singing in his sleep, ‘fol de rol de rol – I have five shillings – my pocket is full of shillings.’ Like Miss Lawrence, Cuthperson spoke of Williams’s strange talk:

Williams talked in his sleep in a very incoherent manner. Witness frequently shook and awakened him. On being asked what was the matter he used to say he had had a most horrid dream. After the murder of the Williamsons, Williams one day claimed to the witness of his dreadful situation, being greatly afflicted with a disorder. The witness advised him to go to a surgeon, when Williams replied – ‘Ah! It is of no consequence, the gallows will get hold of me soon.’ The witness recollected Williams talking only once in his dream, and was crying, ‘run, run.’ He called to him three times and asked him what was the matter. He thought Williams awoke and answered him in a strange manner.

Mr Lee, the landlord of the Black Horse public house, opposite the King’s Arms, was the next witness. He recalled that on the night of Williamson’s murder he had been standing at his own door waiting for his wife and niece to come home from the Royalty Theatre, worrying for their safety, his thoughts on the murders of the Marrs, when suddenly he heard the faint voice of a man crying ‘Watch, watch!’ It seemed to come from Williamson’s house. He afterwards supposed it was the voice of the old man crying out for relief after he had been wounded. It was seven minutes later when he saw Turner descending from the window by the knotted sheets. He was among those who broke into the house and found the bodies. The witness said that he now ‘felt certain’ that more than one man had been concerned in the murders. Asked to name Williams’s friends, he was only able to think of John Cobbett, who had been in bed at the Black Horse at the time of both murders. He, like other witnesses, had had occasion to notice Williams’s familiar ways:

He was accustomed to come into the bar and sit down. He had seen him push against his wife and shake her pockets as if to ascertain what money she had. On one occasion he took the liberty of pulling out the till and putting his hand into it. Witness remonstrated with him and said he never suffered anybody to meddle with his till but his own family. He never thought very seriously of this matter until he heard of Williams being apprehended.

It remained to call three more witnesses – a prostitute and two men who were belie

ved to be friends of Williams. The girl was Margaret Riley. She said she had seen two men ‘run out of Gravel Lane, one of them, as well as she could see, with large whiskers, the other lame.’ She thought that one of the men brought before the magistrates on Tuesday was like one of them. This amounted to very little. But the next witness, said to be a friend of Williams, gave him – if his testimony is to be believed – something of an alibi for the murder of the Williamsons.

John Fitzpatrick proved that he left Williams in company with Hart, the joiner, at the Ship and Royal public house at about quarter past eleven before the murders were committed. This was corroborated by the testimony of Miss Lawrence.

The final witness was believed to be Williams’s only intimate friend, the coal-heaver John Cobbett; and from the little of his evidence that has been reported it seems likely that, under effective cross-examination, he could have shed more light on the mystery than all the other witnesses put together. The Times reported:

John Cobbett said that he had known Williams perfectly well. He got acquainted with him at a public house in New Gravel Lane, where they used to drink together. He had also been with him frequently at Mr Williamson’s, and they had drunk together. But he knew none of his acquaintances. He wished very much to have been able to get something out of him concerning the murders. Indeed, Williams asked him to come and see him during his confinement, but he was never able, in consequence of his being so much employed on board ship.

And the London Chronicle:

John Cobbett, the coal-heaver, being called, pointed out a man named William Ablass, commonly called Long Billy, who was lame, as an intimate friend of Williams. The witness and those two were drinking at Mr Lee’s on the night of the murder of Williamson. Trotter, the carpenter, once said to the witness, ‘It is a very shocking concern, as you would say so indeed if you knew as much as I do.’

The Skull Beneath the Skin

The Skull Beneath the Skin A Taste for Death

A Taste for Death The Children of Men

The Children of Men The Part-Time Job

The Part-Time Job Death in Holy Orders

Death in Holy Orders The Victim

The Victim Shroud for a Nightingale

Shroud for a Nightingale Talking about Detective Fiction

Talking about Detective Fiction Sleep No More

Sleep No More The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories

The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories Time to Be in Earnest

Time to Be in Earnest Original Sin

Original Sin A Mind to Murder

A Mind to Murder Cover Her Face

Cover Her Face Innocent Blood

Innocent Blood Devices and Desires

Devices and Desires Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales

Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales Death Comes to Pemberley

Death Comes to Pemberley The Mistletoe Murder

The Mistletoe Murder Death of an Expert Witness

Death of an Expert Witness The Private Patient

The Private Patient The Black Tower

The Black Tower Devices & Desires - Dalgleish 08

Devices & Desires - Dalgleish 08 Unnatural Causes

Unnatural Causes An Unsuitable Job for a Woman

An Unsuitable Job for a Woman The Murder Room

The Murder Room A Certain Justice

A Certain Justice The Lighthouse

The Lighthouse The Maul and the Pear Tree

The Maul and the Pear Tree