- Home

- P. D. James

Death in Holy Orders Page 19

Death in Holy Orders Read online

Page 19

“I’ve told you, sergeant. I went up to the bedroom to see if my wife was still sleeping.”

“When you opened the door, was the bedside lamp on?”

“No, it wasn’t. The curtains were almost completely drawn and the room was in semi-darkness.”

“Did you go up to the body?”

“I’ve told you, sergeant. I just looked in, saw that my wife was still in bed and assumed that she was asleep.”

“And she went to bed when was that?”

“At lunch-time. I suppose about half-past twelve. She said she wasn’t hungry, that she was going to have a sleep.”

“Didn’t you think it strange that she should still be sleeping after five hours?”

“No, I didn’t. She said that she was tired. My wife often did sleep in the afternoons.”

“Didn’t it occur to you that she might be ill? Didn’t it occur to you to go up to the bed and make sure she was all right? Didn’t you realize that she might urgently need a doctor?”

“I’ve told you I’m tired of telling you1 thought she was asleep.”

“Did you see the two bottles on the bedside table, the wine and the soluble aspirin?”

“I saw the wine bottle. I guessed my wife had been drinking.”

“Did she take the bottle of wine up to bed with her ?”

“No, she didn’t. She must have come down for it after I left the house.”

“And carried it up to bed with her?”

“I suppose so. There was no one else in the house. Of course she took it up to bed with her. How else could it have got on the bedside table?”

“Well, that’s the question, isn’t it sir? You see, there were no fingerprints on the wine bottle. Can you explain how that could be?”

“Of course I can’t. I assume she wiped them off. There was a handkerchief half-under the pillow.”

“Which you were able to see although you couldn’t see the upturned bottle?”

“Not at the time. I saw it later when I found her body.”

And so the questions went on. Yarwood returned time and time again, sometimes with the young uniformed constable, but sometimes on his own. Crampton came to dread every ring at the door and could hardly bear to look out of the windows in case he saw that grey-coated figure moving resolutely up the path. The questions were always the same and his answers became unconvincing even to his own ears. Even after the inquest and the expected verdict of suicide the persecution continued. Barbara had been cremated weeks before. There was nothing left of her but a few handfuls of ground bones buried in a corner of the churchyard, and still Yarwood continued his inquiries.

Never had nemesis arrived in a less personable form. Yarwood looked like a doorstep salesman, doggedly persistent, inured to rejection, carrying with him like halitosis the taint of failure. He was slightly-built, surely only just tall enough to qualify for the police, sallow-skinned and with a high bony forehead and dark secretive eyes. He seldom looked directly at Crampton during the questioning but focused on the middle distance as if communing with an internal controller. His voice never varied from a monotone and the silence between the questions was pregnant with a menace which seemed to embrace more than his victim. He seldom gave notice of his coming but seemed to know when Crampton was at home and would wait with apparently docile patience at the front door until silently ushered in. There were never any preliminaries, only the insistent questions.

“Would you say it was a happy marriage, sir?”

The impertinence of it shocked Crampton into silence, then he found himself replying in a voice of such harshness that he could hardly recognize it: “I suppose that for the police every relationship, even the most sacred, can be classified. You should hand out a marriage questionnaire, it would save everyone time. Tick the appropriate box: Very happy. Happy. Reasonably happy. A little unhappy. Unhappy. Very unhappy. Murderous.”

There was a silence, then Yarwood said, “And which box would you tick, sir?”

In the end Crampton made a formal complaint to the Chief Constable and the visits ceased. He was told that after the inquiry it was accepted that Sergeant Yarwood had exceeded his authority, particularly in arriving alone and pursuing an investigation which had not been authorized. He remained in Crampton’s memory as a dark accusing figure. Time, the new parish, his appointment to

Archdeacon, his second marriage nothing could assuage the burning anger which consumed him whenever he thought of Yarwood.

And now today the man had appeared again. He couldn’t remember what exactly they had said to each other. He only knew that his own resentment and bitterness had been poured out in a torrent of angry vituperation.

He had prayed, at first regularly and then intermittently, since Barbara’s death, asking forgiveness for his sins against her; impatience, intolerance, lack of love, failure to understand or to forgive. But the sin of wishing her dead had never been allowed to take root in his mind. And he had received his absolution to the lesser sin of neglect. It had come in the words of Barbara’s general practitioner when they had met just before the inquest.

“One thing has been on my mind. If I’d realized when I came home that Barbara wasn’t asleep that she was in a coma and had called for an ambulance, would it have made any difference?”

He had received the absolving reply: “With the quantity she had taken and drunk, none at all.”

What was there about this place that forced him to confront the greater as well as the lesser lies? He had known she was in danger of death. He had hoped that she would die. He was in the eyes of his God, surely, as guilty of murder as if he had dissolved those tablets and forced them down her throat, as if he had held the glass of wine to her lips. How could he continue to minister to others, to preach the forgiveness of sins, when his own great sin was unacknowledged? How could he have stood up before that congregation tonight with this darkness in his soul?

He put out his hand and switched on the bedside lamp. It flooded the room with light, surely brighter than when, by that gentle glow, he had read his evening passage of scripture. He got out of bed and knelt, burying his head in his hands. It wasn’t necessary to search for the words; they came to him naturally, and with them came the promise of forgiveness and peace.

“Lord be merciful to me, a sinner.”

It was while he was kneeling there that his mobile telephone on the bedside table broke the silence with its cheerfully incongruous tune. The sound was so unexpected, so discordant, that for five seconds he didn’t recognize it. Then he got stiffly to his feet and put out his hand to answer the call.

Shortly before five-thirty Father Martin woke himself with a shriek of terror. He jerked up in bed and sat, rigid as a doll, staring wild-eyed into the darkness. Beads of sweat ran down his forehead and stung his eyes. Brushing them away he felt his skin taut and ice cold, as if already in the rigor of death. Gradually, as the horror of the nightmare ended, the room took shape around him. Grey forms, more imagined than seen, revealed themselves out of darkness and became comfortingly familiar; a chair, the chest of drawers, the foot board of his bed, the outline of a picture-frame. The curtains over the four circular windows were drawn but from the east he could see a thin sliver of the faint light which even on the darkest night hovered above the sea. He was aware of the storm. The wind had been rising all evening and by the time he had composed himself for sleep it was howling round the tower like a banshee. But now there was a lull more ominous than welcome and, sitting up rigidly, he listened to the silence. He heard no footfall on the stairs, no calling voice.

When the nightmares began two years earlier, he had asked to be given this small circular room in the southern tower, explaining that he liked the wide view of the sea and coast and was attracted by the silence and solitude. The stairs were becoming a tedious climb but at least he could hope that his waking screams would be unheard. But somehow Father Sebastian had guessed the truth, or part of it. Father Martin remembered their brief conversation

one Sunday after Mass.

Father Sebastian had said, “Are you sleeping well, Father?”

“Reasonably so, thank you.”

“If you are disturbed by bad dreams I understand there is help available. I’m not thinking of counselling, not in the ordinary sense, but sometimes talking about the past with others who have suffered the same experience is said to be helpful.”

The conversation had surprised Father Martin. Father Sebastian had made no secret of his distrust of psychiatrists, saying that he would be more inclined to respect them if they could explain the medical or philosophical basis of their discipline, or could define for him the difference between the mind and the brain. But it had always surprised him how much Father Sebastian knew about what was going on under the roof of St. Anselm’s. The conversation had been unwelcome to Father Martin, the matter not pursued. He knew that he was not the only survivor of a Japanese prison camp who was being tormented in old age by horrors which a younger brain had been able to suppress. He had no wish to sit in a circle discussing his experiences with fellow-sufferers, although he had read that some found it helpful. This was something he had to deal with himself.

And now the wind was rising, a rhythmic moaning that rose to a howling and then screeching intensity, more a malignant manifestation than a force of nature. He urged his legs out of bed, pushed his feet into his bedroom slippers and pottered stiffly over to open the east-facing window. The cold blast was like a healing draught, cleaning his mouth and nostrils of the foetid stench of the jungle, drowning the all-too-human moans and screams with its wild cacophony, cleansing his mind of the worst of the images.

The nightmare was always the same. Rupert had been dragged back to the camp the night before and now the prisoners were lined up to watch his beheading. After what had been done to him the boy could hardly walk to the appointed place and sank to his knees as if with relief. But he made a last effort and managed to raise his head before the blade swung down. For two seconds the head remained in place, then slowly it toppled and the great red fountain spurted out like a last celebration of life. This was the image which night after night Father Martin endured.

On waking he was tortured always by the same questions. Why had Rupert tried to escape when he must have known it was suicide? Why hadn’t he confided his purpose? Worst of all, why hadn’t he himself stepped forward in protest before the blade fell, tried with his frail strength to seize it from the guard, and died with his friend? The love he had felt for Rupert, requited but unconsummated, had been the only love of his life. All else had been the exercise of a general benevolence or the practice of loving kindness. Despite the moments of joy, some even of a rare spiritual happiness, he carried always the darkness of that betrayal. He had no right to be alive. But there was one place where he could always find peace and he sought it now.

He took his bunch of keys from the bedside table, shuffled over to the hook on the door and took down his old cardigan with the patches of leather on the elbows which he wore in winter under his cloak. He put the cloak over it, quietly opened the door and made his way down the stairs.

He needed no torch; a low light from a single bulb burned on each landing and the spiral staircase to the floor below, always a hazard, was kept well lit by the use of wall-mounted lights. There was a lull in the storm. The silence of the house was absolute, the muted moaning of the wind emphasizing an internal calm more portentous than the mere absence of human sounds. It was difficult to believe that there were sleepers behind the closed doors, that this silent air had ever echoed to the sound of hurrying feet and strong male voices, or that the heavy oak front door had not been closed and bolted for generations.

In the hall a single red light at the foot of the Virgin and Child cast a glow over the smiling face of the mother and touched with pink the chubby outstretched arms of the Christ-child. Wood was quickened into living flesh. He passed on his silent slippered feet across the hall and into the cloakroom. The row of brown cloaks were the first evidence of the house’s occupation; they seemed to hang like forlorn relics of a long-dead generation. He could hear the wind very clearly now, and as he unlocked the door into the north cloister it rose suddenly into renewed fury.

To his surprise the light over the back door was off, as was the row of low-powered lights along the cloister. But when he stretched out his hand and pressed down the switch they came on and he could see that the stone floor was thick with leaves. Even as he closed the door behind him another gust shook the great tree and sent the drift of leaves around its trunk bowling and scurrying about his feet. They swirled about him like a flock of brown birds, pecked gently against his cheek and lay weightless as feathers on the shoulders of his cloak.

He scrunched his way to the door of the sacristy. It took a little time under the final light to identify the two keys and let himself in. He switched on the light beside the door, then punched out the code to silence the low insistent ringing of the alarm system, and went through into the body of the church. The switch for the two rows of ceiling lights over the nave was to his right and he put out his hand to press it down, then saw with a small shock of surprise but no anxiety that the spotlight which illuminated the Doom was on so that the west end of the church was bathed in its reflected glow. Without switching on the nave lights he moved along the north wall, his shadow moving with him on the stone.

Then he reached the Doom and stood transfixed at the horror that lay sprawled at his feet. The blood hadn’t gone away. It was here in the very place in which he was seeking sanctuary, as red as in his nightmare, not rising like a strong feathered fountain but spread in blotches and rivulets over the stone floor. The stream was no longer moving but seemed to quiver and become viscous as he gazed. The nightmare hadn’t ended. He was still trapped in a place of horror, but one which he couldn’t now escape by waking. That or he was mad. He shut his eyes and prayed, “Dear God, help me.” Then his conscious mind took hold and he opened his eyes and willed himself to look again.

His senses, unable to apprehend the whole scene in the enormity of its horror, were registering it by slow degrees, detail by detail. The smashed skull; the Archdeacon’s spectacles lying a little apart but unbroken; the two brass candlesticks placed one on each side of the body as if in an act of sacrilegious contempt; the Archdeacon’s hands stretched out, seeming to clutch at the stones but looking whiter, more delicate, than his hands had looked in life; the purple padded dressing-gown stiffening with his blood. Finally Father Martin raised his eyes to the Doom. The dancing devil in the front of the picture now wore spectacles, a moustache and a short beard, and his right arm had been elongated in a gesture of vulgar defiance. At the foot of the Doom was a small tin of black paint with a brush lying neatly over the lid.

Father Martin staggered forward and dropped to his knees beside the Archdeacon’s head. He tried to pray but the words wouldn’t come. Suddenly he needed to see other human beings, to hear human feet and human noises, to know the comfort of human companionship. Without thinking clearly he staggered to the west of the church and gave one vigorous tug on the bell pull. The bell sang out as sweetly as ever, but seeming to his ears clamorous in its dread.

Then he went to the south door and, with trembling hands, managed at last to draw back the heavy iron bolts. The wind rushed in, bringing with it a few torn leaves. He left it ajar and walked, more strongly and firmly now, back to the body. There were words he had to say and now he found the strength to say them.

He was still on his knees, the edge of his cloak trailing in the blood, when he heard footsteps and then a woman’s voice. Emma knelt beside him and put her arms round his shoulders. He felt the soft brush of her hair against his cheek and could smell her sweet delicately-scented skin driving from his mind the metallic smell of the blood. He could feel her tremble but her voice was calm. She said, “Come away, Father, come away now. It’s all right.”

But it wasn’t all right. It was never going to be all right again.

He tried to look up at her but couldn’t raise his head; only his lips could move. He whispered, “Oh God, what have we done, what have we done?” And then he felt her arms tighten in terror. Behind them the great south door was creaking wider open.

Dalgliesh usually had little difficulty in getting to sleep, even in an unfamiliar bed. Years of working as a detective had inured his body to the discomforts of a variety of couches and, provided he had a bedside light or a torch for the brief period of reading which was necessary for him before sleep came, his mind could usually let go of the day as easily as did his tired limbs. Tonight was different. His room was propitious for sleep; the bed was comfortable without being soft, the bedside lamp was at the right height for reading, the bedclothes were adequate. But he took up his copy of Seamus Heaney’s translation of Beowulf and read the first five pages with a dogged persistence, as if this were a prescribed nightly ritual instead of a long-awaited pleasure. But soon the poetry took hold and he read steadily until eleven o’clock, then switched off the lamp and composed himself for sleep.

But tonight it didn’t come. That welcome moment eluded him when the mind slips free of the burden of consciousness and sinks unafraid into its little diurnal death. Perhaps it was the fury of the wind keeping him awake. Normally he liked to lie in bed and fall asleep to the sound of a storm, but this storm was different. There would be a lull in the wind, a brief period of total anticipatory peace followed by a low moaning, rising into a howling like a chorus of demented demons. In these crescendos he could hear the great horse-chestnut groaning and had a sudden vision of snapping boughs, of the scarred trunk toppling, first as if reluctant and then in a terrifying plunge to thrust its upper branches through the bedroom window. And always a vibrant accompaniment to the tumult of the wind he could hear the pounding of the sea. It seemed impossible that anything living could stand up to this assault of wind and water.

The Skull Beneath the Skin

The Skull Beneath the Skin A Taste for Death

A Taste for Death The Children of Men

The Children of Men The Part-Time Job

The Part-Time Job Death in Holy Orders

Death in Holy Orders The Victim

The Victim Shroud for a Nightingale

Shroud for a Nightingale Talking about Detective Fiction

Talking about Detective Fiction Sleep No More

Sleep No More The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories

The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories Time to Be in Earnest

Time to Be in Earnest Original Sin

Original Sin A Mind to Murder

A Mind to Murder Cover Her Face

Cover Her Face Innocent Blood

Innocent Blood Devices and Desires

Devices and Desires Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales

Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales Death Comes to Pemberley

Death Comes to Pemberley The Mistletoe Murder

The Mistletoe Murder Death of an Expert Witness

Death of an Expert Witness The Private Patient

The Private Patient The Black Tower

The Black Tower Devices & Desires - Dalgleish 08

Devices & Desires - Dalgleish 08 Unnatural Causes

Unnatural Causes An Unsuitable Job for a Woman

An Unsuitable Job for a Woman The Murder Room

The Murder Room A Certain Justice

A Certain Justice The Lighthouse

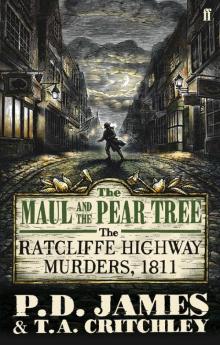

The Lighthouse The Maul and the Pear Tree

The Maul and the Pear Tree