- Home

- P. D. James

Devices & Desires - Dalgleish 08 Page 19

Devices & Desires - Dalgleish 08 Read online

Page 19

Then, still gazing down at the body, Rickards asked: 'Do you know her, Mr Dalgliesh?'

'Hilary Robarts, Acting Administrative Officer at Larksoken Power Station. I met her first last Thursday, at a dinner party given by Miss Mair.'

Rickards turned and gazed towards the figure of Mair. He was standing motionless with his back to the sea but so close to the surf that it seemed to Dalgliesh that the waves must be washing over his shoes. He made no move towards them, almost as if he were waiting for an invitation or for Rickards to join him.

Dalgliesh said: 'Dr Alex Mair. He's the Director of Larksoken. I used the telephone in his car to call you. He says he'll stay here until the body is removed.'

'Then he's in for a long wait. So that's Dr Alex Mair. I've read about him. Who found her?'

'I did. I thought I made that plain when I telephoned.'

Either Rickards was deliberately extracting information he already knew or his men were singularly inefficient at passing on a simple message.

Rickards turned to Oliphant. 'Go and explain to him that we'll be taking our time. There's nothing he can do here except to get in the way. Persuade him to go home to bed. If you can't persuade, try ordering. I'll talk to him tomorrow.' He waited until Oliphant had started scrunching over the ridge of shingle then called: 'Oliphant. If he won't move, tell him to keep his distance. I don't want him any closer. Then get the screens round her. That'll spoil his fun.'

It was the kind of casual cruelty which Dalgliesh didn't expect from him. Something was wrong with the man, something that went deeper than professional stress at having to view yet another of the Whistler's victims. It was as if some half-acknowledged and imperfectly suppressed personal anxiety had been violently released by the sight of the body, triumphing over caution and discipline.

But Dalgliesh, too, felt a sense of outrage. He said: 'The man isn't a voyeur. He's probably not altogether rational at present. After all, he knew the woman. Hilary Robarts was one of his senior officers.'

'He can't do her any good now, even if she was his mistress.' Then, as if acknowledging the implied rebuke, he said: 'All right, I'll have a word with him.'

He began running clumsily over the shingle. Hearing him, Oliphant turned and together they went up to that silent, waiting figure on the fringe of the sea. Dalgliesh watched as they conferred together, then they turned and began walking up the beach, Alex Mair between the two police officers as if he were a prisoner under escort. Rickards returned to the body but it was obvious that Oliphant was going to accompany Alex Mair back to his car. He switched on his torch and plunged into the wood. Mair hesitated. He had ignored the body as if it were no longer there but now he looked over at Dalgliesh as if there were unfinished business between them. Then he said a quick 'Goodnight' and followed Oliphant.

Rickards didn't comment on Mair's change of mind or on his methods of persuasion. He said: 'No handbag.'

'Her house key is in that locket round her neck.' 'Did you touch the body, Mr Dalgliesh?' 'Only her thigh and the hair to test its wetness. The locket was a gift from Mair. He told me.' 'Lives close, does she?'

'You'll have seen her cottage when you drove up. It's just the other side of the pine wood. I went there after I found the body, thinking it might be open and I could telephone. There's been an act of vandalism, her portrait thrown through the window. The Whistler and criminal damage on the same night; an odd coincidence.'

Rickards turned and looked full at him. 'Maybe. But this wasn't the Whistler. The Whistler's dead. Killed himself in a hotel at Easthaven, sometime around six o'clock. I've been trying to reach you to let you know.'

He squatted by the body and touched the girl's face, then lifted the head and let it drop. 'No rigor. Not even the beginning of it. Within the last few hours, by the look of her. The Whistler died with enough sins on his conscience but this . . . this,' he stabbed his finger violently at the dead body, 'this, Mr Dalgliesh, is something different.'

Rickards rolled on his search gloves. The latex sliding over his huge fingers made them look almost obscene, like the udders of a great animal. Kneeling, he fiddled with the locket. It sprang open and Dalgliesh could see the Yale key nestling inside it, a perfect fit. Rickards extracted it, then said: 'Right, Mr Dalgliesh. Let's go and take a look at that criminal damage.'

Two minutes later he followed Rickards up the path to the front door of the cottage. Rickards unlocked it and they passed into a passage running to the stairs and with doors on either side. Rickards opened the door to the left and stepped into the sitting room with Dalgliesh behind him. It was a large room running the whole length of the cottage with windows at each end and a fireplace facing the door. The portrait lay about three feet from the window surrounded by jagged slivers of glass. Both men stood just inside the door and surveyed the scene.

Dalgliesh said: 'It was painted by Ryan Blaney who lives at Scudder's Cottage further south on the headland. I saw it first on the afternoon I arrived.'

Rickards said: 'A funny way of delivering it. Sat for him, did she?'

'I don't think so. It was painted to please himself, not her.'

He was going to add that Ryan Blaney would, in his view, be the last person to destroy his work. But then he reflected that it hadn't, in fact, been destroyed. Two single cuts in the form of an L wouldn't be too difficult to repair. And the damage had been as precise and deliberate as those cuts on Hilary Robarts's forehead. The picture hadn't been slashed in fury.

Rickards seemed for a moment to lose interest in it. He said: 'So this is where she lived. She must have been fond of solitude. That is if she lived alone.'

Dalgliesh said: 'As far as I know she lived alone.'

It was, he thought, a depressing room. It was not that the place was uncomfortable; it held the necessary furniture but the pieces looked as though they were rejects from someone else's house, not the conscious choice of the occupant. Beside the fireplace with its fitted gas fire were two armchairs in synthetic brown leather. In the centre of the room was an oval dining table with four discordant chairs. On either side of the front window were fitted bookshelves, holding what looked like a collection of textbooks and assorted novels. Two of the lower and taller shelves were packed with box files. Only on the longest wall facing the door was there any sign that someone had made this room a home. She had obviously been fond of watercolours and the wall was as closely hung with them as if it had been part of a gallery. There were one or two which he thought he could recognize and he wished he could walk over to examine them more closely. But it was possible that someone other than Hilary Robarts herself had been in this room before them and it was important to leave the scene undisturbed.

Rickards closed the door and opened the opposite one on the right of the passage. This led to the kitchen, a purely functional, rather uninteresting room, well enough equipped but in stark contrast to the kitchen at Martyr's Cottage.

Set in the middle of the room was a small wooden table, vinyl-covered, with four matching chairs all pushed well in. On the table was an uncorked bottle of wine with the cork and the metal opener beside it. Two plain wineglasses, clean and upturned, were on the draining board.

Rickards said: 'Two glasses, both washed, by her or her killer. We'll get no prints there. And an open bottle. Someone was drinking with her here tonight.'

Dalgliesh said: 'If so he was abstemious. Or she was.'

Rickards with his gloved hand lifted the bottle by its neck and slowly turned it. 'About one glass poured. Maybe they planned to finish it after her swim.' He looked at Dalgliesh and said:' 'You didn't come earlier into the cottage, Mr Dalgliesh? I have to ask everyone she knew.'

'Of course. No, I didn't come earlier into the cottage. I Was drinking claret tonight, but not with her.'

'Pity you hadn't been. She'd be alive now.'

'Not necessarily. I might have left when she went to change for her swim. And if she did have someone with her here tonight that's probably what he did.' He paused, won

dered whether to speak, then said: 'The left-hand glass is slightly cracked at the rim.'

Rickards lifted it to the central light and turned it slowly.

'I wish I had your eyesight. It's hardly significant, surely.'

'Some people strongly dislike drinking from a cracked glass. I do myself.'

'In which case why didn't she break it and chuck it away? There's no point in keeping a glass you aren't prepared to drink from. When I'm faced with two alternatives I start by taking the more likely. Two glasses, two drinkers. That's the common-sense explanation.'

It was, thought Dalgliesh, the basis of most police work. Only when the obvious proved untenable was it necessary to explore less likely explanations. But it could also be the first fatally easy step into a labyrinth of misconceptions. He wondered why his instinct insisted that she had been drinking alone. Perhaps because the bottle was in the kitchen not in the sitting room. The wine was a '79 Chateau Talbot, hardly an all-purpose tipple. Why not carry it into the sitting room and do it justice in comfort? On the other hand, if she were alone and had needed only a quick swig before her swim she might hardly have bothered. And if two people had been drinking in the kitchen she had been meticulous in pushing back the chairs. But it was the level of the wine that seemed to him almost conclusive. Why uncork a fresh bottle to pour only two half-glasses? Which didn't, of course, mean that she wasn't later expecting a visitor to help finish it.

Rickards seemed to be taking an unnatural interest in the bottle and its label. Suddenly he said gruffly:

'What time did you leave the mill, Mr Dalgliesh?'

'At 9.15. I looked at the carriage clock on the mantelpiece and checked my watch.'

'And you saw no one during your walk?'

'No one, and no footprints other than hers and mine.'

'What were you actually doing on the headland, Mr Dalgliesh?'

'Walking, thinking.' He was about to add: 'And paddling like a boy,' but checked himself.

Rickards said consideringly: 'Walking and thinking.'

To Dalgliesh's oversensitive ears he made the activities sound both eccentric and suspicious. Dalgliesh wondered what his companion would say if he had decided to confide. 'I was thinking about my aunt and the men who loved her, the fiancé who was killed in 1918 and the man whose mistress she might or might not have been. I was thinking of the thousands of people who have walked along that shore and who are now dead, my aunt among them, and how, as a boy, I hated the false romanticism of that stupid poem about great men leaving their footprints on the sands of time, since that was essentially all that most of us could hope to leave, transitory marks which the next tide would obliterate. I was thinking how little I had known my aunt and whether it was ever possible to know another human being except on the most superficial level, even the women I have loved. I was thinking about the clash of ignorant armies by night, since no poet walks by the sea at moonlight without silently reciting Matthew Arnold's marvellous poem. I was considering whether I would have been a better poet, or even a poet at all, if I hadn't also decided to be a policeman. More prosaically, I was, from time to time, wondering how my life would be changed for better or worse by the unmerited acquisition of three-quarters of a million.'

The fact that he had no intention of revealing even the most mundane of these private musings, the childish secrecy about the paddling, induced an irrational guilt, as if he were deliberately withholding information of importance. After all, he told himself, no man could have been more innocently employed. And it was not as if he were a serious suspect. The idea would probably have struck Rickards as too ridiculous even for consideration, although with logic he would have had to admit that no one who lived on the headland and had known Hilary Robarts could be excluded from the inquiry, least of all because he was a senior police officer. But Dalgliesh was a witness. He had information to give or withhold, and the knowledge that he would have no intention of withholding it didn't alter the fact that there was a difference now in their relationship. He was involved, whether he liked it or not, and he didn't need Rickards to point out that uncomfortable reality. Professionally it was none of his business, but it was his business as a man and a human being.

He was surprised and a little disconcerted to discover how much he had resented the interrogation, mild as it had been. A man was surely entitled to walk along the beach at night without having to explain his reasons to a police officer. It was salutary for him personally to experience this sense of privacy violated, of virtuous outrage which the most innocent of suspects must feel when faced with police interrogation. And he realized anew how much, even from childhood, he had disliked being questioned. 'What are you doing? Where have you been? What are you reading? Where are you going?' He had been the much-wanted only child of elderly parents, burdened by their almost possessive parental concern and over-conscientiousness, living in a village where little the rector's son did was safe from scrutiny. And suddenly, standing here in this anonymous, over-tidy kitchen, he recalled vividly and with heart-stopping pain the moment when his most precious privacy had been violated. He remembered that secluded place, deep in the laurels and elderberries, at the bottom of the shrubbery, the green tunnel of leaves leading to his own three square yards of moist, mould-rich sanctuary, remembered that August afternoon, the crackle of bushes, the cook's great face thrust between the leaves. 'Your ma thought you'd be in here, Master Adam. Rector wants you. What do you do in there, hiding yourself away in all those mucky bushes? Better be playing out in the sunshine.' So the last refuge, the one he had thought totally secret, had been discovered. They had known about it all the time.

He said: 'Oh God from You that I could private be.'

Rickards looked at him. 'What was that, Mr Dalgliesh?'

'Just a quotation that came into my mind.'

Rickards didn't reply. He was probably thinking: 'Well, you're supposed to be a poet. You're entitled.' He gave a last searching look around the kitchen as if by the intensity of his gaze he could somehow compel that unremarkable table and four chairs, the opened bottle of wine, the two washed glasses to yield up their secret.

Then he said: 'I'll lock up here and set someone on guard until tomorrow. I'm due to meet the pathologist, Dr Maitland-Brown, over at Easthaven. He'll take a look at the Whistler and then come straight on here. The forensic biologist should have arrived from the lab by then. You wanted to see the Whistler yourself, didn't you, Mr Dalgliesh? This seems as good a time as any.'

It seemed to Dalgliesh a particularly bad time. One violent death was enough in one night and he was seized with a sudden longing for the peace and solitude of the mill. But there seemed no prospect of sleep for him until the early hours of the morning and there was little point in objecting. Rickards said: 'I could drive you over and bring you back.'

Dalgliesh felt an immediate revulsion at the thought of a car journey tete-a-tete with Rickards. He said: 'If you'll drop me at the mill I'll take my own car. There won't be any reason for me to linger at Easthaven and you may have to wait.'

It surprised him a little that Rickards was willing to leave the beach. Admittedly he had Oliphant and his minions; procedures at the scene of a murder were well established, they would be competent to do what was necessary, and until the forensic pathologist arrived the body couldn't be moved. But he sensed that it was important to Rickards that he and Dalgliesh should see the Whistler's body together and he wondered what forgotten incident in their joint pasts had led to that compulsion.

Balmoral Private Hotel was the last house of an undistinguished nineteenth-century terrace at the unfashionable end of the long promenade. The summer lights were still strung between the Victorian lampposts but they had been turned off and now swung in uneven loops like a tawdry necklace which might scatter its blackened beads at the first strong wind. The season was officially over. Dalgliesh drew up behind the police Rover on the left-hand side of the promenade. Between the road and glittering sea was a children's playground, wire-enc

losed, the gate padlocked, the shuttered kiosk pasted with fading and half-torn posters of summer shows, bizarrely shaped ice-creams, a clown's head. The swings had been looped high and one of the metal seats, caught by the strengthening breeze, rapped out a regular tattoo against the iron frame. The hotel stood out from its drabber neighbours, sprucely painted in a bright blue which even the dull street lighting could hardly soften. The porch light shone down on a large card with the words 'Under new management. Bill and Joy Carter welcome you to Balmoral'. A separate card underneath said simply 'Vacancies'.

As they waited to cross the road while a couple of cars cruised slowly past, the drivers peering for a parking space, Rickards said: 'Their first season. Done quite well up to now, so they say, despite the bloody awful summer. This won't help. They'll get the ghouls, of course, but parents will think twice before booking in with the kiddies for happy family hols. Luckily the place is half-empty at present. Two cancellations this morning, so they've only got three couples and they were all out when Mr Carter found the body and, so far, we've managed to keep them in happy ignorance. They're in bed now, presumably asleep. Let's hope they stay that way.'

The Skull Beneath the Skin

The Skull Beneath the Skin A Taste for Death

A Taste for Death The Children of Men

The Children of Men The Part-Time Job

The Part-Time Job Death in Holy Orders

Death in Holy Orders The Victim

The Victim Shroud for a Nightingale

Shroud for a Nightingale Talking about Detective Fiction

Talking about Detective Fiction Sleep No More

Sleep No More The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories

The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories Time to Be in Earnest

Time to Be in Earnest Original Sin

Original Sin A Mind to Murder

A Mind to Murder Cover Her Face

Cover Her Face Innocent Blood

Innocent Blood Devices and Desires

Devices and Desires Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales

Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales Death Comes to Pemberley

Death Comes to Pemberley The Mistletoe Murder

The Mistletoe Murder Death of an Expert Witness

Death of an Expert Witness The Private Patient

The Private Patient The Black Tower

The Black Tower Devices & Desires - Dalgleish 08

Devices & Desires - Dalgleish 08 Unnatural Causes

Unnatural Causes An Unsuitable Job for a Woman

An Unsuitable Job for a Woman The Murder Room

The Murder Room A Certain Justice

A Certain Justice The Lighthouse

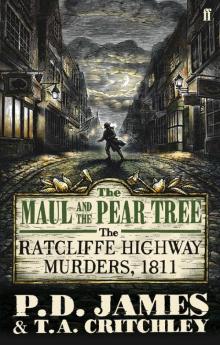

The Lighthouse The Maul and the Pear Tree

The Maul and the Pear Tree