- Home

- P. D. James

Death in Holy Orders Page 21

Death in Holy Orders Read online

Page 21

“What keys do the ordinands have?”

“They each have two keys, one to the iron gate which is their usual mode of entrance, and one to the door either in the north or south cloister depending on the situation of their rooms. None of them has keys to the church.”

“And Ronald Treeves’s keys were returned here after his death?”

“Yes. They’re in a drawer in Miss Ramsey’s office, but he didn’t of course have keys to the church. And now I wish to go to the Archdeacon.”

“Of course. On the way, Father, we can check if the three spare sets of keys to the church are in the key cupboard.”

Father Sebastian didn’t reply. As they passed through the outer office he went over to a narrow cupboard to the left of the fireplace. It was not locked. Inside were two rows of hooks holding named keys. There were three hooks on the first row labelled CHURCH. One was empty.

Dalgliesh said, “Can you remember when you last saw the church keys, Father?”

Father Sebastian thought for a moment and said, “I think it was yesterday morning before lunch. Some paint was delivered for Surtees to paint the sacristy. Pilbeam came in to collect a set of keys and I was here in the office when he signed for them, and still here when he returned them less than five minutes later.”

He went to the right drawer in Miss Ramsey’s desk and drew out a book.

“I think you’ll find here that this was the last entry for the keys. As you see, he held them for no more than five minutes. But the last person to see them would have been Henry Bloxham. He was responsible for making the church ready for Compline last night. I was here when he collected a set of keys and in my office next door when he returned them. If there had been a set missing he would have said so.”

“Did you actually see him return the keys, Father?”

“No. I was in my office but the door between the rooms was open and he called good-night. There will be no entry in the key book. Ordinands who collect the keys before a service are not required to sign it. And now, Commander, I must insist that we go to the church.”

The house was still in silence. They passed without speaking over the tessellated floor of the hall. Father Sebastian was moving towards the door through the cloakroom, but Dalgliesh said, “We’ll avoid the north cloister as far as possible.”

Nothing more was said until they reached the sacristy door. Father Sebastian fumbled for his keys, but Dalgliesh said, “I’ll do this, Father.”

He unlocked the door, locked it after them, and they passed into the church. He had left on the light over the Doom and the horror at its foot was clearly visible. Father Sebastian’s steps didn’t falter as he moved towards it. He didn’t speak, but looked first at the desecration of the painting and then down at his dead adversary. Then he made the sign of the cross and knelt in silent prayer. Watching him, Dalgliesh wondered what words Father Sebastian was finding to communicate with his God. He could hardly be praying for the Archdeacon’s soul; that would have been anathema to Crampton’s uncompromising Protestantism.

He wondered, too, what words he would find appropriate if he were praying at this moment.

“Help me to solve this case with the least pain to the innocent, and protect my team.” The last time he remembered having prayed with passion and with the belief that his prayer was valid had been when his wife was dying, and it had not been heard or, if heard, had not been answered. He thought about death, its finality, its inevitability. Was part of the attraction of his job the illusion it gave that death was a mystery that could be solved,

and with the solution all the unruly passions of life, all doubts and all fears could be folded away like a garment.

And then he heard Father Sebastian speaking as if he had become aware of Dalgliesh’s silent presence and needed to involve him, even if only as a listener in his secret ministry of expiation. The familiar words spoken in his beautiful voice were an affirmation not a prayer and they so uncannily echoed Dalgliesh’s thoughts that he heard them as if for the first time, and with a fris son of awe.

“And thou, Lord, in the beginning has laid the foundation of the earth; and the heavens are the works of thine hands: they shall perish, but thou remain est and they all shall wax old as doth a garment; and as a vesture shalt thou fold them up, and they shall be changed; but thou art the same, and thy years shall not fail.”

Dalgliesh shaved, showered and dressed with practised speed, and by twenty-five minutes past seven had again joined the Warden in his office. Father Sebastian looked at his wrist-watch.

“It’s time to go to the library. I’ll say a few words first and then you can take over. Is that acceptable?”

“Perfectly.”

It was the first time on this visit that Dalgliesh had been in the library. Father Sebastian switched on a series of lights which curved down over the shelves and immediately memory came rushing back of long summer evenings reading here under the sightless eyes of the busts ranged along the top of the shelves, of the western sun burnishing the leather spines and throwing gules of coloured light over polished wood, of long evenings when the boom of the sea seemed to strengthen with the dying light. But now the high barrelled ceiling was in gloom and the stained glass in the pointed windows was a black void patterned with lead.

Along the northern wall a row of bookshelves jutting at right angles between the windows formed cubicles, each with a double reading desk and chair. Father Sebastian went to the nearest cubicle, swung up two chairs and placed them together in the middle of the room. He said, “We’ll need four chairs, three for the women and one for Peter Buckhurst. He’s not yet strong enough to stand for long -not that this will take long, I imagine. There’s no point in putting out a chair for Father John’s sister. She’s elderly and hardly ever shows herself outside their flat.”

Without replying, Dalgliesh helped to carry the last two chairs and Father Sebastian arranged them in line, then stood back as if assessing the accuracy of their placement.

There was the sound of soft footfalls across the hall and the three ordinands, all wearing their black cassocks, came in together as if by prior arrangement and took their stand behind the chairs. They stood upright and very still, their faces set and pale, their eyes fixed on Father Sebastian. The tension they brought into the room was palpable.

They were followed in less than a minute by Mrs. Pilbeam and Emma. Father Sebastian indicated the chairs with a gesture and without speaking the two women sat down, leaning a little towards each other as if there could be comfort even in the slight touch of a shoulder. Mrs. Pilbeam, in recognition of the importance of the occasion, had taken off her white working overall and looked incongruously festive in a green woollen skirt and pale blue blouse adorned with a large brooch at the neck. Emma was very pale but had taken care in dressing, as if attempting to impose order and normality on the disruption of murder. Her brown low-heeled shoes were highly polished and she wore fawn corduroy trousers, a cream blouse which looked freshly ironed, and a leather jerkin.

Father Sebastian said to Buckhurst, “Won’t you sit, Peter?”

“I’d rather stand, Father.”

“I’d prefer you to sit.”

Without further demur Peter Buckhurst took the seat beside Emma.

Next came the three priests. Father John and Father Peregrine stood one on each end of the ordinands. Father Martin, as if recognizing an unspoken invitation, came and stood beside Father Sebastian.

Father John said, “I’m afraid my sister is still asleep and I didn’t like to wake her. If she’s needed, perhaps she could be seen later?”

Dalgliesh murmured, “Of course.” He saw Emma look at Father Martin with loving concern and half rise in her chair. He thought, she’s kind as well as clever and beautiful. His heart lurched, a sensation as unfamiliar as it was unwelcome. He thought, Oh God, not that complication. Not now. Not ever.

And still they waited. Seconds lengthened into minutes before they again heard footsteps. The door opened and George Gregory

entered, closely followed by Clive Stannard. Stannard had either overslept or had seen no reason to inconvenience himself. He had put on his trousers and a tweed jacket over his pyjamas and the striped cotton showed plainly at his neck and was ruched over his shoes. Gregory, in contrast, had dressed with care, his shirt and tie immaculate.

Gregory said, “I’m sorry if I’ve kept you waiting. I dislike putting on my clothes before I’ve showered.”

He took his stand behind Emma and rested his hand on the back of her chair, then quietly slid it away, apparently feeling the gesture had been inappropriate. His eyes, fixed on Father Sebastian, were wary but Dalgliesh thought he detected a hint of amused curiosity.

Stannard was, he thought, frankly frightened and attempting to conceal it by a nonchalance which was as contrived as it was embarrassing.

He said, “Isn’t it a bit early for drama? I take it that something’s happened. Hadn’t we better know?”

No one replied. The door opened again and the last arrivals came in. Eric Surtees was in his working clothes. He hesitated at the door and cast a look of puzzled inquiry at Dalgliesh as if surprised to find him present. Karen Surtees, bright as a parrot in a long red sweater over green trousers, had taken time only to apply a coat of bright red lipstick. Her eyes, denuded of make-up, looked drained and full of sleep. After a moment’s hesitation she took the vacant chair and her brother moved behind her. All those summoned were now present. Dalgliesh thought that they looked like an ill-assorted wedding group, reluctantly posing for an over-enthusiastic photographer.

Father Sebastian said, “Let us pray.”

The exhortation was unexpected. Only the priests and the ordain ds responded instinctively by bowing their heads and clasping their hands. The women seemed uncertain what was expected of them but, after a glance at Father Martin, stood up. Emma and Mrs. Pilbeam bowed their heads and Karen Surtees stared at Dalgliesh with belligerent disbelief as if holding him personally responsible for the embarrassing debacle. Gregory, smiling, stared straight ahead and Stannard frowned and shifted his feet. Father Sebastian spoke the words of the Morning Collect. He paused and then said the prayer which he had spoken at Compline some ten hours earlier.

“Visit, we beseech thee, O Lord, this place, and drive from it all the snares of the enemy; let thy holy angels dwell herein to preserve us in peace; and may thy blessing be upon us evermore; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.”

There was a chorus of “Amen’, subdued from the women, more confident from the ordinands, and the group stirred. It was less a movement than a release of breath. Dalgliesh thought: They know now, of course they know. But one of them has known from the beginning. The women again sat down. Dalgliesh felt the intensity of the gaze fixed on the Warden. When he began speaking, his voice was calm and almost expressionless.

“Last night a great evil came into our community. Archdeacon Crampton has been brutally murdered in the church. His body was discovered by Father Martin at five-thirty this morning. Commander Dalgliesh, who was here as our guest on another matter, is still our guest but is now among us as a police officer investigating a murder. It will be our duty as well as our wish to give him every possible assistance by answering his questions fully and honestly and by doing nothing either by word or action to hinder the police or to make them feel that their presence here is unwelcome. I have telephoned those ordinands who are away this weekend and deferred for a week those due to return this morning. Those of us now here must try to continue the life and work of the college while co-operating fully with the police. I have put St. Matthew’s Cottage at Mr. Dalgliesh’s disposal and the police will be working from there. At Mr. Dalgliesh’s request the church and the access to the north cloister are both closed, as is the cloister itself. Mass will be said in the oratory at the usual time and all services will be held there until the church has been reopened and made ready for divine service. The Archdeacon’s death is now a matter for the police. Don’t speculate, don’t gossip among yourselves. Murder, of course, cannot be kept hidden. Inevitably this news will break, in the Church and in the wider world. I would ask you not to telephone or communicate the news in any way outside these walls. We can hope for at least one day of peace. If there are any matters worrying you, Father Martin and I are here.” He paused and then added, “As always. And now I will ask Mr. Dalgliesh to take over.”

His audience had listened in almost total silence. Only at the sonorous word murdered did Dalgliesh hear a quick intake of breath and a frail cry quickly suppressed which he thought came from Mrs. Pilbeam. Raphael, white-faced, was so rigid that Dalgliesh feared he was about to keel over. Eric Surtees shot a terrified glance at his sister then looked quickly away and fixed his eyes on Father Sebastian. Gregory was frowning in intense concentration. The still cold air was charged with fear. Apart from Surtees’s glance at his sister, none of them met each other’s eyes. Perhaps, thought Dalgliesh, they were afraid of what they might see.

Dalgliesh was interested that Father Sebastian had made no mention of the absence of Yarwood, Pilbeam and Stephen Morby, and was grateful for his discretion. He decided to be brief. It wasn’t his habit when investigating murder to apologize for the inconvenience caused; inconvenience to those involved was the least of murder’s contaminating evils.

He said, “It has been agreed that the Metropolitan Police shall take over this case. A small team of police officers and support services will be arriving this morning. As Father Sebastian has said, the church is closed, as is the north cloister and the door leading from the house to that cloister. I myself or one of my officers will be speaking to you all some time today. However, it would save time if we could establish one fact at once. Did anyone here leave his or her room last night after Compline? Did anyone go near or into the church? Did any of you see or hear anything last night that could have had a bearing on this crime?”

There was silence, then Henry said, “I went out just after ten-thirty for some air and exercise. I walked briskly about five times round the cloisters and then went back to my room. I’m Number Two on the south cloister. I saw and heard nothing unusual. The wind was getting up strongly by then and blowing showers of leaves into the north cloister. That’s chiefly what I remember.”

Dalgliesh said, “You were the ordinand who lit the candles in church before Compline and opened the south door. Did you fetch the church key from the outer office?”

“Yes. I fetched it just before the service and returned it afterwards. There were three keys when I collected it, and three after I had taken it back.”

Dalgliesh said, “I’ll ask again. Did any of you leave your room after Compline?”

He waited for a moment but there was no response. He went on, “I shall want to see the shoes and clothes that you were wearing yesterday evening and it will later be necessary to take the fingerprints of everyone in St. Anselm’s for the purposes of elimination. I think that’s all for the present.”

Again there was a silence, then Gregory spoke.

“A question for Mr. Dalgliesh. Three people seem to be missing, among them an officer of the Suffolk Police. Is there any significance in that fact, I mean for the thrust of the investigation?”

Dalgliesh said, “At present, none.”

This breaking of the silence provoked Stannard into querulous speech. He said, “Can I ask why the Commander is assuming that this must be what I think the police describe as an inside job ? While we are having clothes examined and fingerprints taken, the person responsible is probably miles away. After all, this place is hardly secure. I

for one don’t intend to sleep here tonight without a lock on my door.”

Father Sebastian said, “Your concern is natural. I’m arranging for locks to be fitted to your room and to the four guest sets and keys to be provided.”

“And what about my question? Why the assumption that it must have been one of us ?”

It was the first time that this possibility had been spoken aloud and it seemed to

Dalgliesh that everyone present was determined to stare ahead as if any glance might convey an accusation. He said, “No assumptions are being made.”

Father Sebastian said, “The closing of the north cloister will mean that ordinands with rooms there will have temporarily to vacate them. With so many students absent, that applies at present only to you, Raphael. If you will hand over your keys, a key to room 3 in the south cloister and to the south corridor door will be given in exchange.”

“What about my things, Father, books and clothes? Can’t I fetch them?”

“You must manage without them for the present. Your fellow students will be able to lend you what you need. I can’t emphasize too strongly the importance of keeping away from any area which the police have put out of bounds.”

Without another word Raphael took a bunch of keys from his pocket, detached two and, stepping forward, handed them to Father Sebastian.

Dalgliesh said, “I understand that all the resident priests have keys to the church. Could you please check now that they are in your possession?”

Father Betterton spoke for the first time.

“I’m afraid I haven’t my keys with me. I always leave them on a chair by my bed.”

Dalgliesh still had Father Martin’s bunch of keys which he had taken in the church, and now he moved to the other two priests, checking that the church keys were still on their rings.

He turned to Father Sebastian, who said, “I think that’s all that needs to be said at present. The timetable set up for today will be kept as far as possible. There will be no Morning Prayer but I propose to say Mass in the oratory at midday. Thank you.”

He turned and walked steadily out of the room. There was a shuffling of feet. The little company looked at each other and then, one by one, made for the door.

Dalgliesh had switched off his mobile telephone during the meeting, but now it rang. It was Stephen Morby.

“Commander Dalgliesh? We’ve found Inspector Yarwood. He’d fallen into a ditch about half-way down the approach road. I tried to ring earlier but couldn’t get through. He’s been partly lying in water and he’s unconscious. We think he’s broken a leg. We didn’t like to move him because of making the injury worse, but we felt we couldn’t leave him where he was. We got him out as carefully as we could and rang for an ambulance. He’s being loaded into it now. They’re taking him to Ipswich Hospital.”

The Skull Beneath the Skin

The Skull Beneath the Skin A Taste for Death

A Taste for Death The Children of Men

The Children of Men The Part-Time Job

The Part-Time Job Death in Holy Orders

Death in Holy Orders The Victim

The Victim Shroud for a Nightingale

Shroud for a Nightingale Talking about Detective Fiction

Talking about Detective Fiction Sleep No More

Sleep No More The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories

The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories Time to Be in Earnest

Time to Be in Earnest Original Sin

Original Sin A Mind to Murder

A Mind to Murder Cover Her Face

Cover Her Face Innocent Blood

Innocent Blood Devices and Desires

Devices and Desires Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales

Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales Death Comes to Pemberley

Death Comes to Pemberley The Mistletoe Murder

The Mistletoe Murder Death of an Expert Witness

Death of an Expert Witness The Private Patient

The Private Patient The Black Tower

The Black Tower Devices & Desires - Dalgleish 08

Devices & Desires - Dalgleish 08 Unnatural Causes

Unnatural Causes An Unsuitable Job for a Woman

An Unsuitable Job for a Woman The Murder Room

The Murder Room A Certain Justice

A Certain Justice The Lighthouse

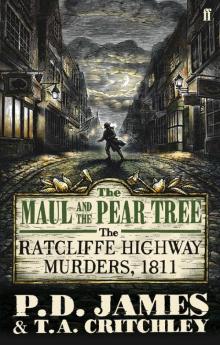

The Lighthouse The Maul and the Pear Tree

The Maul and the Pear Tree