- Home

- P. D. James

Death Comes to Pemberley Page 24

Death Comes to Pemberley Read online

Page 24

‘She was very persuasive. You must remember, Darcy, that I only saw her once when you and I interviewed her as a prospective companion to Miss Georgiana, and you know how impressive and plausible she could be. She was obviously successful financially and had arrived at the inn with her own coach and coachman accompanied by her maid. She produced statements from her bank proving that she was well able to support the child, but said – almost with a smile – that she was a cautious woman and would expect the thirty pounds to be doubled but thereafter there would be no further payments. If the boy were adopted by her, he would be removed from Pemberley for ever.’

Darcy said, ‘You were putting yourself in the power of a woman you knew to be corrupt and who was almost certainly a blackmailer. Apart from the money she received from her lodgers, how else did she live in such opulence? You knew from our previous dealings with her what sort of a woman she was.’

The colonel said, ‘They were your previous dealings, Darcy, not mine. I admit that it was our joint decision that she should take over the care of Miss Darcy, but that was the only previous occasion on which we met. You may have had dealings with her later, but I am not privy to those and have no wish so to be. Listening to her and studying the evidence she brought with her, I was convinced that the solution being offered for Louisa’s baby was both sensible and right. Mrs Younge was obviously fond of the child and willing to make herself responsible for his future maintenance and education; above all he would be totally removed from Pemberley or any association with Pemberley. That was the first consideration to me, and I believe that it would have been to you. I would not have acted against the mother’s wishes for her child, nor have I done so.’

‘Would Louisa really have been happy for her child to be given to a blackmailer and a kept woman? Did you really believe that Mrs Younge would not come back to you for more money time and time again?’

The Colonel smiled. ‘Darcy, I am occasionally surprised at how naive you are, how little you know about the world outside your beloved Pemberley. Human nature is not as black and white as you suppose. Mrs Younge was undoubtedly a blackmailer, but she was a successful one and saw it as a reliable business provided it was run with discretion and sense. It is the unsuccessful blackmailers who end in prison or on the scaffold. She asked what her victims could afford but she never bankrupted them or made them desperate, and she kept to her word. I have no doubt you paid for her silence when you dismissed her from your service. Has she ever spoken of her time when she was in charge of Miss Darcy? And after Wickham and Lydia eloped, and you persuaded her to give you their address, you must have paid heavily for that information, but has she ever spoken of the matter? I am not defending her, I know what she was, but I found her easier to deal with than most of the righteous.’

Darcy said, ‘I am not so naive, Fitzwilliam, as you suppose. I have long known how she operates. So what happened to Mrs Younge’s letter to you? It would be interesting to see what promises she made to induce you not only to support her plan to adopt the child, but to pay over more money. You yourself can hardly be so naive as to suppose Wickham would return his thirty pounds.’

‘I burnt the letter when we spent that night in the library. I waited until you were asleep and then put it in the fire. I could see no further use for it. Even had Mrs Younge’s motives been suspect and she had later broken faith, how could I take legal action against her? It has always been my belief that any letter which contains information which should never be generally known ought to be destroyed; there is no other security. As to the money, I proposed, and with every confidence, to leave it to Mrs Younge to persuade Wickham to part with it. I could be sure that she would succeed; she had experience and inducements which I lacked.’

‘And your early rising in the morning when you suggested that we sleep in the library, and your visit to check on Wickham – were they part of your plan?’

‘If I had found him awake and sober and had the opportunity, I wanted to impress on him that the circumstances under which he received the thirty pounds must remain totally secret and that he should adhere to this in any court unless I myself revealed the truth when he would be free to confirm my statement. I would say, if questioned by the police or in court, that the reason I gave him the thirty pounds was to enable him to settle a debt of honour, which was indeed true, and that I had given my word that the circumstances of this debt would never be revealed.’

Darcy said, ‘I doubt that any court would press Colonel the Lord Hartlep to break his word. They might wish to ascertain whether the money was intended for Denny.’

‘Then I should be able to reply that it was not. It was important to the defence that this was established at the trial.’

‘I have been wondering why, before we set off to find Denny and Wickham, you hurried to see Bidwell and dissuade him from joining us in the chaise and returning to Woodland Cottage. You acted before Mrs Darcy had a chance to issue her instructions to Stoughton or Mrs Reynolds. It struck me at the time that you were being unnecessarily, even presumptuously, helpful; but now I understand why Bidwell had to be kept away from Woodland Cottage that night, and why you went there to warn Louisa.’

‘I was presumptuous, and I make a belated apology. It was, of course, vital that the two women were aware that the plan to collect the baby next morning might have to be abandoned. I was tired of the whole subterfuge and felt that it was time for the truth. I told them that Wickham and Captain Denny were lost in the woodland and that Wickham, the father of Louisa’s child, was married to Mr Darcy’s sister.’

Darcy said, ‘Louisa and her mother must have been left in a state of dreadful distress. It is difficult to imagine the shock to both of them at learning that the child they were nurturing was Wickham’s bastard and that he and a friend were lost in the woodland. They had heard the pistol shots and must have feared the worst.’

‘There was nothing I could do to reassure them. There wasn’t time. Mrs Bidwell gasped out, “This will kill Bidwell. Wickham’s son here in Woodland Cottage! The stain on Pemberley, the appalling shock for the master and Mrs Darcy, the disgrace for Louisa, for us all.” It is interesting that she put them in that order. I was worried for Louisa. She almost fainted, then crept to a fireside chair and sat there violently shivering. I knew she was in shock but there was nothing I could do. I had already been absent for longer than you, Darcy, and Alveston could have expected.’

Darcy said, ‘Bidwell, his father and grandfather before him had lived in that cottage and served the family. Their distress was a natural loyalty. And, indeed, had the child remained at Pemberley, or even visited Pemberley regularly, Wickham could have gained an entrance to my family and my house that I would have found deeply repugnant. Neither Bidwell nor his wife had ever met the adult Wickham, but the fact that he is my brother and still never welcomed must have told them how deep and eradicable was the severance between us.’

The colonel said, ‘And then we found Denny’s body, and by the morning Mrs Younge and everyone at the King’s Arms, and indeed in the whole neighbourhood, would know of the murder in Pemberley woodland and that Wickham had been arrested. Could anyone believe that Pratt left the King’s Arms that night without telling his story? I have no doubt Mrs Younge’s reaction would be to return immediately to London, and without the child. That may not mean that she had permanently given up any hope of the adoption, and perhaps Wickham, when he arrives, will enlighten us on that point. Will Mr Cornbinder be with him?’

Darcy said, ‘I imagine so. He has apparently been of great service to Wickham and I hope that his influence will last, although I am not sanguine. For Wickham he is probably too much associated with a prison cell, the vision of a noose, and with months of sermons to wish to spend any more time in his company than is necessary. When he does arrive we shall hear the rest of this lamentable story. I am sorry, Fitzwilliam, that you should have become involved in the affairs of Wickham and myself. It was an unfortunate day for you when you saw Wickh

am and handed over that thirty pounds. I accept that in supporting Mrs Younge’s proposal to adopt the boy you were acting in his interests. I can only hope that the poor child, with so appalling a beginning, has settled happily and permanently with the Simpkinses.’

2

Shortly after luncheon a clerk in Alveston’s office arrived to confirm that the royal pardon would be granted by mid-afternoon the next day, and to hand Darcy a letter to which he said no immediate response was expected. It came from the Reverend Samuel Cornbinder from Coldbath Prison, and Darcy and Elizabeth sat down and read it together.

Reverend Samuel Cornbinder

Coldbath Prison

Honoured Sir

You will be surprised to receive this communication at the present time from a man who is to you a stranger, although Mr Gardiner, whom I have met, may have spoken of me, and I must begin by apologising for intruding on your privacy when you and your family will be celebrating the deliverance of your brother from an unjust charge and an ignominious death. However, if you will have the goodness to peruse what I write, I am confident that you will agree that the matter I raise is both important and of some urgency and that it affects yourself and your family.

But I must first introduce myself. My name is Samuel Cornbinder and I am one of the chaplains appointed to the Coldbath prison where it has been my privilege for the last nine years to minister both to the accused awaiting their trial and to those who have been condemned. Among the former has been Mr George Wickham, who will shortly be with you to give you the explanation about the circumstances leading up to Captain Denny’s death, to which, of course, you are entitled.

I shall place this letter in the hands of the Honourable Mr Henry Alveston, who will deliver it with a message from Mr Wickham. He has desired that you read it before he appears before you in order that you may be aware of the part I have played in his plans for the future. Mr Wickham bore his imprisonment with notable fortitude but, not unnaturally, he was occasionally overcome by the possibility of a guilty verdict, and it was then my duty to direct his thoughts to the One who alone can forgive us all that has passed and fortify us for what may lie ahead. Inevitably in our discussions I learned much about his childhood and subsequent life. I must make it plain that, as an evangelical member of the Church of England, I do not believe in auricular confession but I would like to assure you that all matters confided in me by prisoners remain inviolate. I encouraged Mr Wickham’s hopes of a not-guilty verdict and in his moments of optimism – which I am glad to say have been many – he has addressed his mind to his future and that of his wife.

Mr Wickham has expressed the strongest desire not to remain in England, but to seek his fortune in the New World. Happily I am in a position to help him in this resolve. My twin brother, Jeremiah Cornbinder, emigrated five years ago to the former colony of Virginia where he established a business schooling and selling horses, at which, largely due to his knowledge and skill, he has prospered exceedingly. Owing to the expansion of the business he is now looking for an assistant, one who is experienced with horses, and just over a year ago wrote to engage my interest in the matter and to say that any candidate I recommend will be kindly received and established in the post for a trial period of six months. When Mr Wickham was received into Coldbath Prison and I began my visits to him, I early recognised that he had qualities and experience which would eminently make him a suitable candidate for employment by my brother if, as he hoped and expected, he was found not guilty of a grievous charge. Mr Wickham is a fine horseman and has shown that he is courageous. I discussed the matter with him and he is anxious to take advantage of this opportunity and, although I have not spoken to Mrs Wickham, he assures me that she is equally enthusiastic to leave England and to take advantage of the opportunities available in the New World.

There is, however, as you may well foresee, a problem about money. Mr Wickham hopes that you will be good enough to make him a loan of the sum required, which will comprise the cost of the passage and a sufficient income to last for four weeks before he receives his first pay. A house will be provided rent-free and the horse farm – for that is what my brother’s business may be called – is within two miles of the city of Williamsburg. Mrs Wickham will not therefore be deprived of company and of those refinements which a gently born lady will require.

If these proposals meet with your approval and you are able to help, I will gladly wait upon you at any hour and place convenient to you and will provide you with details of the sum required, the accommodation to be offered, and letters of recommendation which will assure you of my brother’s standing in Virginia and of his character which, I need hardly say, is exceptional. He is a just man and a fair employer, but not one who will tolerate dishonesty or laziness. If it is possible for Mr Wickham to take up an offer for which he shows enthusiasm, it will remove him from all temptations. His deliverance and his record as a brave soldier will make him into a national hero and, however briefly such fame may last, I fear this notoriety will hardly be conducive to the reform of his life which he assures me he is determined to make.

I can be reached at any time of the day or night at the above address, and can reassure you of my goodwill in this matter and my willingness to provide you with any information which you may require about the situation offered.

I remain, dear sir, yours very sincerely,

Samuel Cornbinder

Darcy and Elizabeth read the letter in silence, then without comment Darcy handed it to the colonel.

Darcy said, ‘I think I must see this reverend gentleman, and it is as well that we know of this plan before we see Wickham. If the offer is as genuine and appropriate as it seems it will certainly solve Bingley’s and my problem, if not Wickham’s. I have yet to learn how much it will cost me, but if he and Lydia remain in England, we can hardly expect that they can live without regular help.’

Colonel Fitzwilliam said, ‘I suspect that both Mrs Darcy and Mrs Bingley have been contributing to Wickham’s expenses from their own resources. To put it bluntly, this affair will relieve both families of financial obligation. In respect of Wickham’s future behaviour, I find it difficult to share the reverend gentleman’s confidence in his reformation, but I suspect that Jeremiah Cornbinder will be more competent than Wickham’s family in ensuring his future good conduct. I shall be happy to contribute to the sum needed, which I imagine will not be onerous.’

Darcy said, ‘The responsibility is mine. I shall reply at once to Mr Cornbinder in the hope that we can meet early tomorrow before Wickham and Alveston are due.’

3

The Reverend Samuel Cornbinder arrived after church the following day in reply to a letter from Darcy delivered to him by hand. His appearance was unexpected since, from his letter, Darcy had envisaged a man in late middle age or older, and he was surprised to see that Mr Cornbinder was either considerably younger than his literary style suggested or had managed to endure the rigours and responsibilities of his job without losing the appearance and vigour of youth. Darcy expressed his gratitude for all that the reverend gentleman had done to help Wickham to endure his captivity, but without mentioning Wickham’s apparent conversion to a better mode of life, about which he was incompetent to comment. He liked Mr Cornbinder, who was neither too solemn nor unctuous, and who came with a letter from his brother and with all the necessary financial information to enable Darcy to make an informed decision on the extent to which he should and could help in establishing Mr and Mrs Wickham in the new life which they seemed heartily to desire.

The letter from Virginia had been received some three weeks ago. In it Mr Jeremiah Cornbinder expressed confidence in his brother’s judgement and, while not overstating what advantages the New World could offer, gave a reassuring picture of the life which a recommended candidate could expect.

The New World is not a refuge for the indolent, the criminal, the undesirable or the old, but a young man who has been clearly acquitted of a capital crime, has shown fortitude dur

ing his ordeal and has shown outstanding bravery in the field of battle appears to have the qualifications which will ensure his welcome. I am looking for a man who combines practical skills, preferably in the schooling of horses, with a good education and I am confident that he will be joining a society which, in intelligence and the breadth of its cultural interests, can equal that found in any civilised European city and which offers opportunities which are almost limitless. I think I can confidently predict that the descendants of those whom he now hopes to join will be citizens of a country as powerful, if not more powerful, than the one they have left, and one which will continue to set an example of freedom and liberty to the whole world.

Reverend Cornbinder said, ‘As my brother can rely on my judgement in recommending Mr Wickham, so do I rely on his goodwill in doing all he can to help the young couple feel at home and flourish in the New World. He is particularly anxious to attract immigrants from England who are married. When I wrote to recommend Mr Wickham it was two months before his trial, but I was optimistic both that he would be acquitted and that he was exactly the man for whom my brother was seeking. I make judgements about prisoners quickly and have not yet been wrong. While respecting Mr Wickham’s confidence, I have intimated that there are some aspects of his life which would cause a prudent man to hesitate, but I have been able to assure my brother that Mr Wickham has changed and is resolved to maintain this change. Certainly his virtues outweigh his faults, and my brother is not so unreasonable as to expect perfection. We have all sinned, Mr Darcy, and we cannot look for mercy without showing it in our lives. If you are willing to supply the cost of the passage and the moderate sum necessary for Mr Wickham to support himself and his wife for the first few months of his employment, it will be possible for them to sail from Liverpool on the Esmeralda within two weeks. I know the captain and have every faith both in him and in the amenities of the vessel. I expect you will need some hours to think this over, and no doubt to discuss it with Mr Wickham, but it would be helpful if I could have a decision by nine o’clock tomorrow night.’

The Skull Beneath the Skin

The Skull Beneath the Skin A Taste for Death

A Taste for Death The Children of Men

The Children of Men The Part-Time Job

The Part-Time Job Death in Holy Orders

Death in Holy Orders The Victim

The Victim Shroud for a Nightingale

Shroud for a Nightingale Talking about Detective Fiction

Talking about Detective Fiction Sleep No More

Sleep No More The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories

The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories Time to Be in Earnest

Time to Be in Earnest Original Sin

Original Sin A Mind to Murder

A Mind to Murder Cover Her Face

Cover Her Face Innocent Blood

Innocent Blood Devices and Desires

Devices and Desires Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales

Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales Death Comes to Pemberley

Death Comes to Pemberley The Mistletoe Murder

The Mistletoe Murder Death of an Expert Witness

Death of an Expert Witness The Private Patient

The Private Patient The Black Tower

The Black Tower Devices & Desires - Dalgleish 08

Devices & Desires - Dalgleish 08 Unnatural Causes

Unnatural Causes An Unsuitable Job for a Woman

An Unsuitable Job for a Woman The Murder Room

The Murder Room A Certain Justice

A Certain Justice The Lighthouse

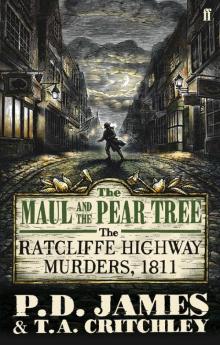

The Lighthouse The Maul and the Pear Tree

The Maul and the Pear Tree