- Home

- P. D. James

Death in Holy Orders Page 40

Death in Holy Orders Read online

Page 40

Raphael said, “The note in my edition says it refers to a card game. Winner takes all. So I suppose Herbert’s saying that when he’s writing poetry he holds the hand of God, the winning hand.”

Emma said, “Herbert is fond of gaming puns. Remember The Church Porch? This could be a card game where you give up cards in order to obtain better ones. We mustn’t forget Herbert’s talking about his poetry. When he’s writing it he has everything because he’s one with God. His readers at the time would have known the card game he was referring to.”

Henry said, “I wish I did. We should do some research, I suppose, and find how it was played. It shouldn’t be difficult.”

Raphael protested.

“But pointless. I want the poem to lead me to the altar and silence, not to a reference book or a pack of cards.”

“Agreed. This is typical Herbert, isn’t it? The mundane, even the frivolous, sanctified. But I’d still like to know.”

Emma’s eyes were on her book and she was only aware that someone had come into the library when the four students simultaneously rose to their feet. Commander Dalgliesh stood in the doorway. If he was disconcerted to find that he had interrupted a seminar, he didn’t show it, and his apology, made to Emma, sounded more conventional than heartfelt.

“I’m sorry, I didn’t realize you were using the library. I’d like a word with Father John Betterton and was told I’d find him here.”

Father John, a little flustered, began to edge himself out of his low leather chair. Emma knew that she was blushing but, since there was no way of concealing the tell-tale flush, made herself meet Dalgliesh’s dark unsmiling eyes. She didn’t get up, and it seemed to her that the four ordinands had moved closer to her chair, like a cassock-clad bodyguard silently confronting an intruder.

Raphael’s voice was ironic and over-loud.

“The words of Mercury are harsh after the songs of Apollo. The poet detective, just the man we need. We’re grappling with a problem with George Herbert. Why not join us, Commander, and contribute your expertise?”

Dalgliesh regarded him for a few seconds in silence, then said, “I’m sure Miss Lavenham has all the expertise necessary. Shall we go, Father?”

The door closed behind them and the four ordinands sat down. For Emma the episode had had an importance beyond the words spoken or the glances exchanged. She thought, the Commander doesn’t like Raphael. He wasn’t, she felt, a man who would ever let personal feelings intrude into his professional life. Almost certainly he wouldn’t now. But she felt quietly sure that she hadn’t misread that small spark of antagonism. What was odder was her own brief moment of pleasure at the thought.

Father Betterton trotted beside him across the hall, out of the front door and round the south of the house to the cottage, accommodating his short legs to Dalgliesh’s stride like an obedient child, his hands folded within his black cloak. He seemed more embarrassed than worried. Dalgliesh had wondered how he would react to police questioning. In his experience anyone whose previous encounters with the police had resulted in arrest was never afterwards at ease with them. He had feared that Father Betterton’s trial and imprisonment, which surely must have been for him an appallingly traumatic experience, might have left him unable to cope. Kate had described how he had reacted with stoically controlled revulsion to the taking of his prints but then, few potential suspects welcomed this official thieving of identity. Apart from this, Father John had seemed less obviously affected both by the murder and by the death of his sister than were the rest of the community, preserving always the same look of puzzled acceptance of a life which had to be endured rather than possessed.

In the interview room he seated himself on the edge of the chair with no sign that he was expecting an ordeal. Dalgliesh asked, “Were you responsible, Father, for packing up Ronald Treeves’s clothes for return to his father?”

Now the faint impression of embarrassment was replaced by an unmistakable guilty flush.

“Oh dear, I think I may have done something foolish. You wanted to ask about the cloak, I expect.”

“Did you send it back, Father?”

“No. No, I’m afraid I didn’t. It’s rather difficult to explain.” He was still more embarrassed than frightened as he looked across at Kate.

“It would be easier if I could have your other officer here, Inspector Tarrant. You see, it’s all rather embarrassing.”

That wasn’t a request to which Dalgliesh would normally have agreed, but the circumstances were unusual. He said, “As a police officer Inspector Miskin is used to embarrassing confidences. But if you would feel happier…”

“Oh yes indeed. Yes please, I should. I know it’s foolish of me but it would be easier.”

At a nod from Dalgliesh, Kate slipped out. Piers was busy upstairs seated at the computer.

She said, “Father Betterton has something to say unsuitable for my chaste female ears. AD wants you. It looks as if Treeves’s cloak was never sent back to Dad. If so, why the hell weren’t we told before? What’s wrong with these people?”

Piers said, “Nothing. It’s just that they don’t think like policemen.”

“They don’t think like anyone I’ve ever met. Give me a good old-fashioned villain any day.”

Piers gave up his seat to her and went down to the interviewing room.

Dalgliesh said, “So exactly what happened, Father?”

“I expect Father Sebastian told you that he asked me to bundle up the clothes. He thought well, we thought that it wouldn’t be fair to ask one of the staff to do it. The clothes of dead people are so personal to them, aren’t they? It’s always a distressing business. So I went to Ronald’s room and got them together. He didn’t have much, of course. The students aren’t encouraged to bring too many possessions or clothes with them, only what is needed. I put the things together, but when I was folding the cloak I noticed that…” He hesitated, and then said, “Well, I noticed that it was stained on the inside.”

“How was it stained, Father?”

“Well, it was obvious that he’d been lying on the cloak and making love.”

Piers said, “It was a semen stain?”

“Yes. Yes it was. Quite a big one really. I felt I didn’t want to send the cloak back to his father like that. Ronald wouldn’t have wished me to and I knew well, we all knew that Sir Aired hadn’t wanted him to come to St. Anselm’s, hadn’t wanted him to be a priest. If he’d seen the cloak he could’ve made trouble for the college.”

“You mean a sexual scandal?”

“Yes, something like that. And it would have been so humiliating for poor Ronald. It was the last thing he would have wanted to happen. I wasn’t very clear in my mind but it just seemed wrong to send the cloak back in the state it was in.”

“Why didn’t you attempt to clean it?”

“Well I did think about that, but it wouldn’t have been very easy. I was afraid that my sister would see me carrying it about and ask me what I was doing. And I’m not very good at washing things. And of course I didn’t want to be seen doing it. The flat is small and we have we had very little privacy from each other. I just put the problem aside. I know it was silly, but I had to get the parcel ready for Sir Alred’s chauffeur and I thought I would deal with it another time. And there was another problem1 didn’t really want anyone here to know, I didn’t want Father Sebastian to be told. You see, I knew who it was. I knew the woman he had been making love to.”

Piers said, “So it was a woman?”

“Oh yes, it was a woman. I know I can tell you this in confidence.”

Dalgliesh said, “If it has no bearing on the murder of the Archdeacon there’s no reason why anyone but ourselves should know it. But I think I can help you. Was it Karen Surtees?”

Father Betterton’s face showed his relief.

“Yes it was. Yes, I’m afraid that’s right. It was Karen. You see I’m rather fond of bird-watching and I saw them through my binoculars. They were in the bracken together. Of course I

didn’t tell anyone. It’s the kind of thing Father Sebastian would find it very difficult to overlook. And then there’s Eric Surtees. He’s a good man and he’s happy here with us and his pigs. I didn’t want to say anything that would upset the arrangement. And it didn’t seem such a terrible thing to me. If they loved each other, if they were happy together… But of course I don’t know how it was with them. I don’t know anything about it really. But when one thinks of the cruelty and pride and selfishness which we often condone, well, I couldn’t feel that what Ronald did was so very terrible. He wasn’t really happy here, you know. He didn’t fit in somehow and I don’t think he was happy at home either. So perhaps he needed to find someone who would show him sympathy and kindness. Other people’s lives are so mysterious, aren’t they? We mustn’t judge. We owe the dead our pity and understanding as well as the living. So I prayed about it and decided to say nothing. Only, of course, I was left with the problem of the cloak.”

Dalgliesh said, “Father, we need to find it quickly. What did you do with it?”

“I rolled it up as tightly as I could and pushed it to the back of my wardrobe. I know it sounds foolish but it seemed sensible at the time. There didn’t really seem any hurry about it. But the days passed and it became more difficult. Then on that Saturday I realized I must make some kind of decision. I waited until my sister was taking a walk. I took one of my handkerchiefs and held it under the hot tap and rubbed it well with soap and managed to clean the cloak quite effectively. I rubbed it dry with a towel and held it in front of the gas fire. Then I thought the best thing would be to take off the name tab so that people weren’t reminded of Ronald’s death. After that I went down and hung it in the cloakroom on one of the pegs. That way if any of the ordinands forgot their cloaks they could use it. I decided that after I’d done that I would explain to Father Sebastian that the cloak hadn’t been sent off with the other clothes, without giving an explanation: I’d tell him I’d hung it in the cloakroom. I knew he’d just assume I’d been careless and forgotten about it. It really seemed the best way.”

Dalgliesh had learnt from experience that to hurry a witness was to invite disaster. Somehow be controlled his impatience. He said, “And where is the cloak now, Father?”

“Isn’t it on the peg where I hung it, the peg on the extreme right? I hung it there just before Compline on Saturday. Isn’t it still there? Of course, I couldn’t check not that I thought of it because you’ve locked the cloakroom door.”

“When exactly did you hang it there ?”

“As I’ve explained, just before Compline. I was one of the first to go into the church. There were very few of us with so many students away and their cloaks were hanging in a row. Of course, I didn’t count them. I just hung Ronald’s cloak where I’ve told you, on the last peg.”

“Father, did you at any time wear the cloak while it was in your possession?”

Father Betterton’s puzzled eyes looked into his.

“Oh no, I wouldn’t have done that. We’ve our own black cloaks. I wouldn’t have needed to wear Ronald’s.”

“Do the students normally wear their own cloaks only, or are they, as it were, communal?”

“Oh, they wear their own. I dare say sometimes they may get muddled but that wouldn’t have happened that night. None of the ordinands wear their cloaks to Compline except in the bitterest winter. It’s only a short walk to the church along the north cloister. And Ronald would never have lent his cloak to anyone else. He was very fussy about his belongings.”

Dalgliesh asked, “Father, why didn’t you tell me this earlier?”

Father John’s puzzled eyes looked into his.

“You didn’t ask me.”

“But didn’t it occur to you when we examined all the cloaks and clothes for blood that we would need to know if any were missing?”

Father John said simply, “No. And it wasn’t missing, was it? It was on a peg in the cloakroom with the others.” Dalgliesh waited. Father John’s mild confusion had deepened into distress. He looked from Dalgliesh to Piers and saw no comfort in their faces. He said, “I hadn’t thought about the details of your investigation, what you were doing or what it all might mean. I didn’t want to and it didn’t seem any of my business. All I’ve done is to try to answer honestly any questions you’ve put to me.”

It was, Dalgliesh had to admit, a complete vindication. Why should Father John have thought the cloak significant? Someone more knowledgeable in police procedure, more curious or interested, would have volunteered the information even if not expecting it to be particularly useful. Father John was none of these things, and even if it had occurred to him to speak, the protection of Ronald Treeves’s pathetic secret would probably have seemed more important.

Now he said contritely, “I’m sorry. Have I made things difficult for you? Is it important?”

And what, thought Dalgliesh, could he honestly answer to that. He said, “What is important is the exact time you hung the cloak on the end peg. You’re sure that it was just before Compline ?”

“Oh yes, quite sure. It would have been nine-fifteen. I’m usually among the first into the church for Compline - I was going to mention the matter to Father Sebastian after the service, but he hurried away and I didn’t get the chance. And next morning, when we all heard about the murder, it seemed such an unimportant thing to worry him with.”

Dalgliesh said, “Thank you for being so helpful, Father. What you’ve told us is important. It is even more important that you keep it private. I’d be grateful if you wouldn’t mention this conversation to anyone.”

“Not even to Father Sebastian?”

“Not to anyone, please. When the investigation is over you’ll be free to tell Father Sebastian as much as you choose. At present I don’t want anyone here to know that Ronald Treeves’s cloak is somewhere in college.”

“But it won’t be somewhere, will it?” The guileless eyes looked at him.

“Isn’t it still be on the peg?”

Dalgliesh said, “It isn’t on the peg now, Father, but I expect we’ll find it.”

Gently he steered Father Betterton to the door. The priest seemed suddenly to have become a confused and worried old man. But at the door he gathered strength and turned to speak a few last words.

“Naturally I shan’t tell anyone about this conversation. You’ve asked me not to do so and I won’t. May I please also ask you to say nothing about Ronald Treeves’s relationship with Karen.”

Dalgliesh said, “If it is relevant to the death of Archdeacon Crampton it will have to come out. Murder is like that, Father. There’s very little we can keep secret when a human being has been done to death. But it will only be revealed if and when it is necessary.”

Dalgliesh impressed on Father John again the importance of telling no one about the cloak and let him go. There was, he thought, one advantage of dealing with the priests and ordinands of St. Anselm’s: you could be reasonably certain that a promise, once given, would be kept.

Less than five minutes later the whole team, including the SO COs were behind the closed doors of St. Matthew’s Cottage. Dalgliesh reported the new development. He said, “Right. So we begin the search. We need first to be clear about the three sets of keys. After the murder only one set was missing. During the night Surtees took a set and didn’t return it. That set has been recovered from the pigsty. That means that Cain must have taken the second set and replaced it after the murder. Assuming that Cain was the figure wearing the cloak, this could be hidden anywhere, inside the college or out. It’s not an easy thing to conceal but Cain had the whole headland and shore available and plenty of time between midnight and five-thirty. It could even have been burnt. There are plenty of ditches crossing the headland where a fire wouldn’t be noticed, even if someone were abroad. All he would need would be some paraffin and a match.”

Piers said, “I know what I’d have done with it, sir. I’d have fed it to the pigs. Those animals will eat anything, particula

rly if it’s bloodstained, in which case we’ll be lucky to find anything except perhaps the small brass chain at the back of the neck.”

Dalgliesh said, “Then look for it. You and Robbins had better make a start with St. John’s Cottage. We’ve been given authority by Father Sebastian to go where we like, so no warrant is necessary. If any of the people in the cottages makes trouble, we may need a warrant. It’s important no one knows what we’re looking for. Where are the ordinands at present, does anyone know?”

Kate said, “I think they’re in the lecture room on the first floor. Father Sebastian is giving them a seminar on theology.”

“That should keep them occupied and out of the way. Mr. Clark, will you and your team take the headland and the shore. I doubt whether Cain would have made his way through that storm to chuck the cloak into the sea, but there are plenty of hiding places on the headland. Kate and I will take the house.”

The group dispersed, the SO COs turning seaward and Piers and Robbins making their way towards St. John’s Cottage. Dalgliesh and

Kate went through the iron gate into the west courtyard. The north cloister was now free of leaves but nothing of interest had been discovered from the SO COs meticulous search except the small twig, its leaves still fresh, on the floor of Raphael’s set.

Dalgliesh unlocked the door of the cloakroom. The air smelt un fresh The five hooded cloaks hung on their pegs in a sad decrepitude as if they had been there for decades. Dalgliesh put on his search gloves and turned back the hood of each cloak. The name tabs were in place: Morby, Arbuthnot, Buckhurst, Bloxham, McCauley. They passed into the laundry-room. There were two high windows with a Formica-topped table beneath them and under it four plastic laundry baskets. To the left was a deep porcelain sink with a wooden draining-board each side, and a tumble-drier. The four large washing machines were fixed to the right-hand wall. All the porthole doors were closed.

Kate stood in the doorway while Dalgliesh opened the first three doors. As he bent to the fourth, she saw him stiffen and went up to him. Behind the thick glass, blurred but identifiable, were the folds of a brown woollen garment. They had found the cloak.

The Skull Beneath the Skin

The Skull Beneath the Skin A Taste for Death

A Taste for Death The Children of Men

The Children of Men The Part-Time Job

The Part-Time Job Death in Holy Orders

Death in Holy Orders The Victim

The Victim Shroud for a Nightingale

Shroud for a Nightingale Talking about Detective Fiction

Talking about Detective Fiction Sleep No More

Sleep No More The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories

The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories Time to Be in Earnest

Time to Be in Earnest Original Sin

Original Sin A Mind to Murder

A Mind to Murder Cover Her Face

Cover Her Face Innocent Blood

Innocent Blood Devices and Desires

Devices and Desires Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales

Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales Death Comes to Pemberley

Death Comes to Pemberley The Mistletoe Murder

The Mistletoe Murder Death of an Expert Witness

Death of an Expert Witness The Private Patient

The Private Patient The Black Tower

The Black Tower Devices & Desires - Dalgleish 08

Devices & Desires - Dalgleish 08 Unnatural Causes

Unnatural Causes An Unsuitable Job for a Woman

An Unsuitable Job for a Woman The Murder Room

The Murder Room A Certain Justice

A Certain Justice The Lighthouse

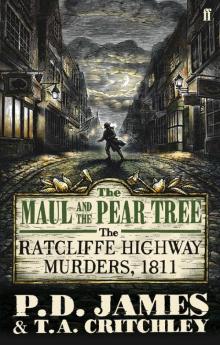

The Lighthouse The Maul and the Pear Tree

The Maul and the Pear Tree