- Home

- P. D. James

Cover Her Face Page 6

Cover Her Face Read online

Page 6

"In the circumstances I think I could," said Dalgleish.

The bedroom was white-walled and full of light. After the dimness of the hall and corridors bounded with oak linen-fold panelling, this room struck with the artificial brightness of a stage. The corpse was the most unreal of all, a second-rate actress trying unconvincingly to simulate death. Her eyes were almost closed, but her face held that look of faint surprise which he had often noticed on the faces of the dead. Two small and very white front teeth were clenched against the lower lip, giving a rabbit-look to a face which, in life, must, he felt, have been striking, perhaps even beautiful. An aureole of hair flamed over the pillow in incongruous defiance of death. It felt slightly damp on his hand. Almost he wondered that its brightness had not drained away with the life of her body. He stood very still looking down at her. He was never conscious of pity at moments like this and not even of anger, although that might come later and would have to be resisted.

He liked to fix the sight of the murdered body firmly in his mind. This had been a habit since his first big case seven years ago when he had looked down at the battered corpse of a Soho prostitute in silent resolution and had thought, "This is it. This is my job."

The photographer had completed his work with the body before the police surgeon began his examination. He was now finishing with shots of the room and the window before packing up his equipment.

The print man had likewise finished with Sally and intent on his private world of whorls and composites, was moving with unobtrusive efficiency from door-knob to lock, from cocoa-beaker to chest of drawers, from bed to window-ledge before heaving himself out on the ladder to work on the stack-pipe and on the ladder itself. Dr. Feltman, the police surgeon, balding, rotund and self-consciously cheerful, as if under a perpetual compulsion to demonstrate his professional imperturbability in the face of death, was replacing his instruments in a black case.

Dalgleish had met him before and knew him for a first-class doctor who had never learned to appreciate where his job ended and the detective's began. He waited until Dalgleish had turned away from the body before speaking.

"We're ready to take her away now if that's all right by you. It looks simple enough medically speaking. Manual strangulation by a right-handed person standing in front of her. She died quickly, possibly by vagal inhibition. I'll be able to tell you more after the P.M. There's no sign of sexual interference but that doesn't mean that sex wasn't the motive. I imagine there's nothing like finding a dead body on your hands to take away the urge. When you pull him in you'll get the same old story, (I put my hands round her neck to frighten her and she went all limp'. He got in by the window by the look of it. You might find fingerprints on that stack-pipe but I doubt whether the ground will be much help. It's a kind of courtyard underneath. No nice soft earth with a couple of handy sole marks.

Anyway, it rained pretty hard last night which doesn't help matters. Well, I'll go and get the stretcher party if your man here has finished. Nasty business for a Sunday morning."

He went and Dalgleish inspected the room. It was large and sparsely furnished, but the overall impression it gave was one of sunlight and comfort. He thought that it had probably previously been the family day nursery. The old-fashioned fireplace on the north wall was surrounded by a heavy meshed fireguard behind which an electric fire had been installed. On each side of the fireplace were deep recesses fitted with bookcases and low cupboards.

There were two windows. The smaller oriel window against which the ladder stood was on the west wall and looked over the courtyard to the old stables. The larger window ran almost the whole length of the south wall, giving a panoramic view of the lawns and gardens. Here the glass was old and set with occasional medallions. Only the top mullioned windows could be opened.

The cream-painted single bed was set at right-angles to the smaller window and had a chair on one side and a bedside table with a lamp on the other. The child's cot was in the opposite corner half-hidden by a screen. It was the kind of screen which Dalgleish remembered from his own childhood, composed of dozens of colored pictures and postcards stuck in a pattern and glazed over. There were a rug before the fireplace and a low nursing chair. Against the wall were a plain wardrobe and a chest of drawers.

There was a curious anonymity about the room. It had the intimate fecund atmosphere of almost any nursery compounded of the faint smell of talcum powder, baby-soap and warmly-aired clothes. But the girl herself had impressed little of her personality on her surroundings. There was none of the feminine clutter which he had half expected. Her few personal belongings were carefully arranged but they were uncommunicative. Primarily it was just a child's nursery with a plain bed for his mother. The few books on the shelves were popular works on baby care. The half-dozen magazines were those devoted to the interests of mothers and housewives rather than to the more romanticized and varied concerns of young workingwomen.

He picked one from the shelf and flicked through it. From its pages dropped an envelope bearing a Venezuelan stamp. It was addressed to:

D. Pullen, Esq.,

Rose Cottage, Nessingford-road,

Little Chadfleet, Essex, England.

On the reverse were three dates scribbled in pencil - Wednesday 18th, Monday 23rd, Monday 30th.

Prowling from the bookshelf to the chest of drawers, Dalgleish pulled out each drawer and systematically turned over its contents with practised fingers. They were in perfect order. The top drawer held only baby clothes. Most of them were handknitted, all were well washed and cared for. The second was full of the girl's own underclothes, arranged in neat piles. It was the third and bottom drawer which held the surprise.

"What do you make of this?" he called to Martin.

The sergeant moved to his chief’s side with a silent swiftness which was disconcerting in one of his build. He lifted one of the garments in his massive fist.

"Hand-made by the look of it, sir.

Must have embroidered it herself, I suppose. There's almost a drawer full. It looks like a trousseau to me." ‹I think that's what it is all right. And not only clothes too. Table-cloths, hand towels, cushion covers." He turned them over as he spoke. "It's rather a pathetic little dowry, Martin. Months of devoted work pressed away in lavender bags and tissue paper. Poor little devil. Do you suppose this was for the delight of Stephen Maxie? I can hardly picture these coy tray-clothes being used in Martingale."

Martin picked one up and examined it appreciatively.

"She can't have had him in mind when she did this. He only proposed yesterday according to the Super and she must have been working on this for months. My mother used to do this kind of work. You buttonhole round the pattern and then cut out the middle pits. Richelieu or something they call it. Pretty effect it gives - if you like that sort of thing," he added in deference to his Chief*s obvious lack of enthusiasm. He ruminated over the embroidery in nostalgic approval before yielding it up for replacement in the drawer.

Dalgleish moved over to the oriel window. The wide window-ledge was about three feet high. It was scattered now with the bright glass fragments of a collection of miniature animals. A penguin lay wingless on its side and a brittle dachshund had snapped in two. One Siamese cat, startlingly blue of eye, was the sole survivor among the splintered holocaust.

The two largest and middle sections of the window opened outwards with a latch and the stack-pipe, skirting a similar window about six feet below, ran directly to the paved terrace beneath. It would hardly be a difficult descent for anyone reasonably agile. Even the climb up would be possible. He noticed again how safe from unwanted observation such an entry or exit would be. To his right the great brick wall, half hidden by overhanging beech boughs, curved away towards the drive. Immediately facing the window and about thirty yards away were the old stables with their attractive clock turret.

From their open shelter the window could be watched, but from nowhere else. To the left only a small part of the lawn was visible. Someo

ne seemed to have been messing about with it. There was a small patch ringed with cord where the grass had been hacked or cut. Even from the window Dalgleish could see the lifted sods and the rash of brown soil beneath.

Superintendent Manning had come up behind him and answered his unspoken question.

"That's Doctor Epps's treasure hunt.

He's had it in the same spot for the last twenty years. They had the church fete here yesterday. Most of the bunting's down - the vicar likes to get the place cleared up before Sunday - but it takes a day or two to erase all the evidence."

Dalgleish remembered that the Super was almost a local man. "Were you here?" he asked.

"Not this year. I've been on duty almost continuously for the last week.

We've still got that killing on the county border to clear up. It won't be long now, but I've been pretty tied up with it. The wife and I used to come over here once a year for the fete but that was before the war. It was different then. I don't think we'd bother now. They still get a fair crowd though. Someone could have met the girl and-found out from her where she slept. It's going to mean a lot of work checking on her movements during yesterday afternoon and evening." His tone implied that he was glad the job was not his.

Dalgleish did not theorize in advance of his facts. But the facts he had garnered so far did not support this comfortable thesis of an unknown casual intruder. There had been no sign of attempted sexual assault, no evidence of theft. He had a very open mind on the question of that bolted door.

Admittedly, the Maxie family had all been on the right side of it at 7 a.m. that morning, but they were presumably as capable as anyone else of climbing down stack-pipes or descending ladders.

The body had been taken away, a white-sheeted lumpy shape stiff on the stretcher, destined for the pathologist's knife and the analyst's bottle. Manning had left them to telephone his office.

Dalgleish and Martin continued their patient inspection of the house. Next to Sally's room was an old-fashioned bathroom, the deep bath boxed round with mahogany and the whole of one wall covered with an immense airing-cupboard, fitted with slatted shelves. The three remaining walls were papered in an elegant floral design faded with age and there was an old but still unworn fitted carpet on the floor. The room offered no possible hiding-place. From the landing outside a flight of drugget-covered stairs curved down to the paneled corridor which led on the one side to the kitchen quarters and on the other to the main hall. Just at the bottom of these stairs was the heavy south door. It was ajar, and Dalgleish and Martin passed out of the coolness of Martingale into the heavy heat of the day.

Somewhere the bells of a church were ringing for Sunday matins. The sound came clearly and sweetly across the trees bringing to Martin a memory of boyhood's country Sundays and to Dalgleish a reminder that there was much to be done and little left of the morning.

"We'll have a look at that old stable block and the west wall beneath her window. After that I'm rather interested in the kitchen. And then we'll go on with the questioning. I've a feeling that the person we're after slept under this roof last night."

In the drawing-room the Maxies with their two guests and Martha Bultitaft waited to be questioned, unobtrusively watched over by a detective-sergeant who had stationed himself in a small chair by the door and who sat in apparently solid indifference, seeming far more at his ease than the owners of the house. His charges had their various reasons for wondering how long they would be kept waiting, but no one liked to reveal anxiety by asking.

They had been told that Detective Chief Inspector Dalgleish from Scotland Yard had arrived and would be with them shortly. How shortly no one was prepared to ask. Felix and Deborah were still in their riding-clothes. The others had dressed hurriedly. All had eaten little and now they sat and waited. Since it would have seemed heartless to read, shocking to play the piano, unwise to talk about the murder and unnatural to talk about anything else, they sat in almost unbroken ins silence. Felix Hearne and Deborah were together on the sofa but sitting a little apart and occasionally he leaned across to whisper something in her ear. Stephen Maxie had stationed himself at one of the windows and stood with his back to the room. It was a stance which, as Felix Hearne had noticed cynically, enabled him to keep his face hidden and to demonstrate an inarticulate sorrow with the back of his bent head. At least four of the watchers would have liked very much to know whether the sorrow was genuine. Eleanor Maxie sat calmly in a chair apart. She was either numbed by grief or thinking deeply.

Her face was very pale but the brief panic which had caught her at Sally's door was over now. Her daughter noticed that she at least had taken trouble in her dressing and was presenting an almost normal appearance to her family and guests.

Martha Bultitaft also sat a little apart, ill at ease on the edge of her chair and darting occasional furious looks at the sergeant whom she obviously held responsible for her embarrassment at having to sit with the family and in the drawing-room, too, while there was work to be done. She who had been the most upset and terrified at the morning's discovery now seemed to regard the whole thing as a personal insult, and she sat in sullen resentment. Catherine Bowers gave the greatest appearance of ease. She had taken a small notebook from her handbag and was writing in it at intervals as if refreshing her memory about the events of the morning. No one was deceived by this appearance of normality and efficiency, but they all envied her the opportunity of putting up so good a show. All of them sat in essential isolation and thought their own thoughts. Mrs. Maxie kept her eyes on the strong hands folded in her lap but her mind was on her son.

"He will get over it, the young always do. Thank God Simon will never know.

It's going to be difficult to manage the nursing without Sally. One oughtn't to think about that I suppose. Poor child.

There may be fingerprints on that lock.

The police will have thought of that.

Unless he wore gloves. We all know about gloves these days. I wonder how many 11 r people got through that window to her. I suppose I ought to have thought of it, but how could I? She had the child with her after all. What will they do with Jimmy?

A mother murdered and a father he'll never know now. That was one secret she kept. One of many probably. One never knows people. What do I know about Felix? He could be dangerous. So could this chief inspector. Martha ought to be seeing to luncheon. That is, if anyone wants luncheon. Where will the police feed? Presumably they'll only want to use our rooms today. Nurse will be here at twelve so I'll have to go to Simon then. I suppose I could go now if I asked.

Deborah is on edge. We all are. If only we can keep our heads."

Deborah thought "I ought to dislike her less now that she's dead, but I can't. She always did make trouble. She would enjoy watching us like this, sweating on the top line. Perhaps she can. I mustn't get morbid. I wish we could talk about it. We might have kept quiet about Stephen and Sally if Eppy and Miss Liddell hadn't been at dinner. And Catherine of course.

There's always Catherine. She's going to enjoy this all right. Felix knows that Sally was doped. Well, if she was, it was in my drinking mug. Let them make what they like of that."

Felix Hearne thought, "They can't be much longer. The thing is not to lose my temper. These will be English policemen, extremely polite English policemen asking questions in strict compliance with judges' rules. Fear is the devil to hide. I can imagine Dalgleish's face if I decided to explain. Excuse me, Inspector, if I appear to be terrified of you. The reaction is purely automatic, a trick of the nervous system. I have a dislike of formal questioning, and even more of the carefully staged informal session. I had some experience of it in France. I have recovered completely from the effects, you understand, except for this one slight legacy. I tend to lose my temper. It is only pure bloody funk. I am sure you will understand, Herr Inspector. Your questions are so very reasonable. It is unfortunate that I mistrust reasonable questions. We mustn't get this thing out of proportion of course. This

is a minor disability. A comparatively small part of one's life is spent in being questioned by the police. I got off lightly. They even left me some of my finger-nails. I'm just trying to explain that I may find it difficult to give you the answers you want."

Stephen turned round.

"What about a lawyer?" he asked suddenly. "Oughtn't we to send for Jephson?"

His mother looked up from a silent contemplation of her folded hands.

"Matthew Jephson is motoring somewhere on the the continent. Lionel is in London.

We could get him if you feel it to be necessary."

Her voice held a note of interrogation.

Deborah said impulsively, "Oh, Mummy!

Not Lionel Jephson. He's the world's most pompous bore. Let's wait until we're arrested before we encourage him to come beetling down. Besides, he's not a criminal lawyer. He only knows about trusts and affidavits and documents. This would shock his respectable soul to the core.

He couldn't help."

"What about you, Hearne?" asked

Stephen.

"I'll cope unaided, thank you."

"We should apologize for mixing you up in this," said Stephen with stiff formality. "It's unpleasant for you and may be inconvenient. I don't know when you'll get back to London." Felix thought that this apology should more appropriately be made to Catherine Bowers. Stephen was apparently determined to ignore the girl. Did the arrogant young fool seriously believe that this death was merely a matter of unpleasantness and inconvenience? He looked across at Mrs. Maxie as he replied.

"I shall be very glad to stay -voluntarily or involuntarily - if I can be of use."

Catherine was adding her eager assurances to the same effect when the silent sergeant, galvanized into life, sprang to attention in a single movement. The door opened and three plainclothes policemen came in. Superintendent Manning they already knew. Briefly he introduced his companions as Detective Chief-Inspector Adam Dalgleish and Detective-Sergeant George Martin. Five pairs of eyes swung simultaneously to the taller stranger in fear, appraisal or frank curiosity.

The Skull Beneath the Skin

The Skull Beneath the Skin A Taste for Death

A Taste for Death The Children of Men

The Children of Men The Part-Time Job

The Part-Time Job Death in Holy Orders

Death in Holy Orders The Victim

The Victim Shroud for a Nightingale

Shroud for a Nightingale Talking about Detective Fiction

Talking about Detective Fiction Sleep No More

Sleep No More The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories

The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories Time to Be in Earnest

Time to Be in Earnest Original Sin

Original Sin A Mind to Murder

A Mind to Murder Cover Her Face

Cover Her Face Innocent Blood

Innocent Blood Devices and Desires

Devices and Desires Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales

Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales Death Comes to Pemberley

Death Comes to Pemberley The Mistletoe Murder

The Mistletoe Murder Death of an Expert Witness

Death of an Expert Witness The Private Patient

The Private Patient The Black Tower

The Black Tower Devices & Desires - Dalgleish 08

Devices & Desires - Dalgleish 08 Unnatural Causes

Unnatural Causes An Unsuitable Job for a Woman

An Unsuitable Job for a Woman The Murder Room

The Murder Room A Certain Justice

A Certain Justice The Lighthouse

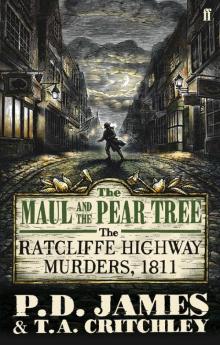

The Lighthouse The Maul and the Pear Tree

The Maul and the Pear Tree