- Home

- P. D. James

The Murder Room Page 6

The Murder Room Read online

Page 6

Emma said, “God help them today for that matter. The system’s as brutal in its own way, isn’t it? It’s just that at least we can organize it ourselves, and there is an alternative.”

Clara laughed. “I don’t see what you’ve got to complain of. You’ll hardly be hopping on and off the carousel. You’ll be sitting up there on your gleaming steed repelling all boarders. And why make it sound as if the merry-go-round is always heterosexual? We’re all looking. Some of us get lucky, and those who don’t generally settle for second best. And sometimes second best turns out to be the best after all.”

“I don’t want to settle for second best. I know who I want and what I want, and it isn’t a temporary affair. I know that if I go to bed with him it will cost me too much if he breaks it off. Bed can’t make me more committed than I am now.”

The London train rumbled into platform one. Clara put down her duffle-bag and they hugged briefly.

Emma said, “Until Friday, then.”

Impulsively Clara clasped her arms round her friend again. She said, “If he chucks you on Friday, I think you should consider whether there’s any future for the two of you.”

“If he chucks me on Friday, perhaps I shall.”

She stood, watching but not waving, until the train was out of sight.

6

From childhood the word London had conjured up for Tallulah Clutton a vision of a fabled city, a world of mystery and excitement. She told herself that the almost physical yearning of her childhood and youth was neither irrational nor obsessive; it had its roots in reality. She was, after all, a Londoner by birth, born in a two-storey terraced house in a narrow street in Stepney; her parents, grandparents and the maternal grandmother after whom she had been named had been born in the East End. The city was her birthright. Her very survival had been fortuitous and in her more imaginative moods she saw it as magical. When the street was destroyed in a bombing raid in 1942 only she, four years old, had been lifted from the rubble alive. It seemed to her that she had a memory of that moment, rooted perhaps in her aunt’s account of the rescue. As the years passed she was uncertain whether she remembered her aunt’s words or the event itself; how she was lifted into the light, grey with dust but laughing and spreading out both arms as if to embrace the whole street.

Exiled in childhood to a corner shop in a suburb of Leeds to be brought up by her mother’s sister and her husband, a part of her spirit had been left in that ruined street. She had been conscientiously and dutifully brought up, and perhaps loved, but as neither her aunt nor uncle was demonstrative or articulate, love was something she neither expected nor understood. She had left school at fifteen, her intelligence recognized by some of the teachers, but there was nothing they could do about it. They knew that the shop awaited her.

When the young gentle-faced accountant who came regularly to audit the books with her uncle began to appear more often than was necessary and to show his interest in her, it seemed natural to accept his eventual and somewhat tentative offer of marriage. There was, after all, enough room in the flat above the shop and room enough in her bed. She was nineteen. Her aunt and uncle made plain their relief. Terence no longer charged for his services. He helped part-time in the shop and life became easier. Tally enjoyed his regular if unimaginative lovemaking and supposed that she was happy. But he had died of a heart attack nine months after the birth of their daughter and the old life was resumed: the long hours, the constant financial anxiety, the welcome yet tyrannical jangle of the bell on the shop door, the ineffectual struggle to compete with the new supermarkets. Her heart would be torn with a desperate pity as she saw her aunt’s futile efforts to entice back the old customers; the outer leaves shredded from cabbages and lettuces to make them look less wilted, the advertised bargains which could deceive no one, the willingness to give credit in the hope that the bill would eventually be paid. It seemed to her that her youth had been dominated by the smell of rotting fruit and the jangle of the bell.

Her aunt and uncle had willed her the shop and when they died, within a month of each other, she put it on the market. It sold badly; only masochists or unworldly idealists were interested in saving a failing corner shop. But it did sell. She kept £10,000 of the proceeds, handed over the remainder to her daughter who had long since left home, and set out for London and a job. She had found it at the Dupayne Museum within a week and had known, when first being shown round the cottage by Caroline Dupayne and seeing the Heath from her bedroom window, that she had come home.

Through the overburdened and stringent years of childhood, her brief marriage, her failure as a mother, the dream of London had remained. In adolescence and later, it had strengthened and had taken on the solidity of brick and stone, the sheen of sunlight on the river, the wide ceremonial avenues and narrow byways leading to half-hidden courtyards. History and myth were given a local habitation and a name and imagined people made flesh. London had received her back as one of its own and she had not been disappointed. She had no naÏve expectations that she walked always in safety. The depiction in the museum of life between the wars told what she already knew, that this London was not the capital her parents had known. Theirs had been a more peaceable city and a gentler England. She thought of London as a mariner might think of the sea; it was her natural element but its power was awesome and she encountered it with wariness and respect. On her weekday and Sunday excursions she had devised her protective strategies. Her money, just sufficient for the day, was carried in a money-bag worn under her winter coat or lighter summer jacket. The food she needed, her bus map and a bottle of water were carried in a small rucksack on her back. She wore comfortable stout walking shoes and, if her plans included a long visit to a gallery or museum, carried a light folding canvas stool. With these she moved from picture to picture, one of a small group which followed the lectures at the National Gallery or the Tate, taking in information like gulps of wine, intoxicated with the richness of the bounty on offer.

On most Sundays she would attend a church, quietly enjoying the music, the architecture and the liturgy, taking from each an aesthetic rather than a religious experience, but finding in the order and ritual the fulfilment of some unidentified need. She had been brought up as a member of the Church of England, sent to the local parish church every Sunday morning and evening. She went alone. Her aunt and uncle worked fifteen hours a day in their desperate attempt to keep the corner shop in profit, and their Sundays were marked by exhaustion. The moral code by which they lived was that of cleanliness, respectability and prudence. Religion was for those who had the time for it, a middle-class indulgence. Now Tally entered London’s churches with the same curiosity and expectation of new experience as she entered the museums. She had always believed—somewhat to her surprise—that God existed but was unconvinced that He was moved by the worship of man or by the tribulations and extraordinary vagaries and antics of the creation He had set in being.

Each evening she would return to the cottage on the edge of the Heath. It was her sanctuary, the place from which she ventured out and to which she returned, tired but satisfied. She could never close the door without an uplifting of her spirits. Such religion as she practised, the nightly prayers she still said, were rooted in gratitude. Until now she had been lonely but not solitary; now she was solitary but never lonely.

Even if the worst happened and she was homeless, she was determined not to seek a home with her daughter. Roger and Jennifer Crawford lived just outside Basingstoke in a modern four-bedroomed house which was part of what the developers had described as “two crescents of executive houses.” The crescents were cut off from the contamination of non-executive housing by steel gates. Their installation, fiercely fought for by householders, was regarded by her daughter and son-in-law as a victory for law and order, the protection and enhancement of property values and a validation of social distinction. There was a council estate hardly half a mile down the road, the inhabitants of which were considered to be inadequately c

ontrolled barbarians.

Sometimes Tally thought that the success of her daughter’s marriage rested not only on shared ambition, but on their common willingness to tolerate, even to sympathize, with the other’s grievances. Behind these reiterated complaints lay, she realized, mutual self-satisfaction. They thought that they had done very well for themselves and would have been deeply chagrined had any of their friends thought otherwise. If they had a genuine worry it was, she knew, the uncertainty of her future, the fact that they might one day be required to give her a home. It was a worry she understood and shared.

She hadn’t visited her family for five years except for three days at Christmas, that annual ritual of consanguinity which she had always dreaded. She was received with a scrupulous politeness and a strict adherence to accepted social norms which didn’t hide the absence of real warmth or genuine affection. She didn’t resent this—whatever she herself was bringing to the family, it wasn’t love—but she wished there was some acceptable way of excusing herself from the visit. She suspected that the others felt the same but were inhibited by the need to observe social conventions. To have one’s widowed and solitary mother for Christmas was accepted as a duty and, once established, couldn’t be avoided without the risk of sly gossip or mild scandal. So punctiliously on Christmas Eve, by a train they had suggested as convenient, she would arrive at Basingstoke station to be met by Roger or Jennifer, her over-heavy case taken from her like the burden it was, and the annual ordeal would get under way.

Christmas at Basingstoke was not peaceful. Friends arrived, smart, vivacious, effusive. Visits were returned. She had an impression of a succession of overheated rooms, flushed faces, yelling voices and raucous conviviality underlined with sexuality. People greeted her, some she felt with genuine kindness, and she would smile and respond before Jennifer tactfully moved her away. She didn’t wish her guests to be bored. Tally was relieved rather than mortified. She had nothing to contribute to the conversations about cars, holidays abroad, the difficulty of finding a suitable au pair, the ineffectiveness of the local council, the machinations of the golf club committee, their neighbours’ carelessness over locking the gates. She hardly saw her grandchildren except at Christmas dinner. Clive spent most of the day in his room, which held the necessities of his seventeen-year-old life: the television, video and DVD player, computer and printer, stereo equipment and speakers. Samantha, two years younger and apparently in a permanent state of disgruntlement, was rarely at home and, when she was, spent hours secreted with her mobile phone.

But now all this was finished. Ten days ago, after careful thought and three or four rough drafts, Tally had composed the letter. Would they mind very much if she didn’t come this year? Miss Caroline wouldn’t be in her flat over the holiday and if she, too, went away there would be no one to keep an eye on things generally. She wouldn’t be spending the day alone. There were a number of friends who had issued invitations. Of course it wouldn’t be the same as coming to the family, but she was sure they would understand. She would post her presents in early December.

She had felt some guilt at the dishonesty of the letter, but it had produced a reply within days. There was a touch of grievance, a suggestion that Tally was allowing herself to be exploited, but she sensed their relief. Her excuse had been valid enough; her absence could safely be explained to their friends. This Christmas she would spend alone in the cottage and already she had been planning how she would pass the day. The morning walk to a local church and the satisfaction of being one of a crowd and yet apart, which she enjoyed, a poussin for lunch with, perhaps, one of those miniature Christmas puddings to follow and a half-bottle of wine, hired videos, library books and, whatever the weather, a walk on the Heath.

But these plans were now less certain. The day after her daughter’s letter arrived, Ryan Archer, coming in after his stint in the garden, had hinted that he might be alone for Christmas. The Major was thinking of going abroad. Tally had said impulsively, “You can’t spend Christmas in the squat, Ryan. You can come here for dinner if you like. But give me a few days’ notice because of getting in the food.”

He had accepted, but tentatively, and she doubted whether he would choose to exchange the camaraderie of the squat for the placid tedium of the cottage. But the invitation had been given. If he came she would at least ensure that he was properly fed. For the first time in years she was looking forward to Christmas.

But now all her plans were overlaid with a fresh and more acute anxiety. Would this coming Christmas be the last she would spend in the cottage?

7

The cancer had returned and this time it was a death sentence. That was James Calder-Hale’s personal prognosis and he accepted it without fear and with only one regret: he needed time to finish his book on the inter-war years. He didn’t need long; it would be finished in four to six months even if his pace slowed. Time might still be granted, but even as the word came into his mind he rejected it. “Granted” implied the conferment of a benefit. Conferred by whom? Whether he died sooner or later was a matter of pathology. The tumour would take its own time. Or, if you wanted to describe it even more simply, he would be lucky or unlucky. But in the end the cancer would win.

He found himself unable to believe that anything he did, anything done to him, his mental attitude, his courage or his faith in his doctors, could alter that inevitable victory. Others might prepare to live in hope, to earn that posthumous tribute, “after a gallant fight.” He hadn’t the stomach for a fight, not with an enemy already so entrenched.

An hour earlier his oncologist had broken the news that he was no longer in remission with professional tact; after all, he had had plenty of experience. He had set out the options for further treatments, and the results which might reasonably be hoped for, with admirable lucidity. Calder-Hale agreed to the recommended course after spending a little time pretending to consider the options, but not too much time. The consultation was taking place at the consultant’s Harley Street rooms, not at the hospital, and, despite the fact that his was the first appointment, the waiting-room was already beginning to fill up by the time he was called. To speak his own prognosis, his complete conviction of failure, would be an ingratitude amounting to bad manners when the consultant had taken so much trouble. He felt that it was he who was bestowing the illusion of hope.

Coming out into Harley Street, he decided to take a taxi to Hampstead Heath station and walk across the Heath past Hampstead Ponds and the viaduct to Spaniards Road and the museum. He found himself mentally summing up his life with a detached wonder that fifty-five years which had seemed so momentous could have left him with so meagre a legacy. The facts came into his mind in short staccato statements. Only son of a prosperous Cheltenham solicitor. Father unfrightening, if remote. Mother extravagant, fussily conventional, but no trouble to anyone except her husband. Education at his father’s old school, and then Oxford. The Foreign Office and a career, chiefly in the Middle East, which had never progressed beyond the unexceptional. He could have climbed higher but he had demonstrated those two fatal defects: lack of ambition and the impression of taking the Service with insufficient seriousness. A good Arabic speaker with the ability to attract friendship but not love. A brief marriage to the daughter of an Egyptian diplomat who had thought she would like an English husband but had quickly decided that he was not the one. No children. Early retirement following the diagnosis of a malignancy which had unexpectedly and disconcertingly gone into remission.

Gradually, since the diagnosis of his illness, he had dissociated himself from the expectations of life. But hadn’t this happened years before? When he had wanted the relief of sex he had paid for it, discreetly, expensively and with the minimum expenditure of time and emotion. He couldn’t now remember when he had finally decided that the trouble and expense were no longer worthwhile, not so much an expense of spirit in a waste of shame, as a waste of money in an expanse of boredom. The emotions, excitements, triumphs, failures, pleasures an

d pains which had filled the interstices of this outline of a life had no power to disturb him. It was difficult to believe that they ever had.

Wasn’t accidie, that lethargy of the spirit, one of the deadly sins? To the religious there must seem a wilful blasphemy in the rejection of all joy. His ennui was less dramatic. It was more a placid non-caring in which his only emotions, even the occasional outbursts of irritation, were mere play-acting. And the real play-acting, that boys’ game which he had got drawn into more from a good-natured compliance than from commitment, was as uninvolving as the rest of his non-writing existence. He recognized its importance but felt himself less a participant than the detached observer of other men’s endeavours, other men’s follies.

And now he was left with the one unfinished business, the one task capable of enthusing his life. He wanted to complete his history of the inter-war years. He had been working on it for eight years now, since old Max Dupayne, a friend of his father’s, had introduced him to the museum. He had been enthralled by it and an idea which had lain dormant at the back of his mind had sprung into life. When Dupayne had offered him the job of curator, unpaid but with the use of an office, it had been a propitious encouragement to begin writing. He had given a dedication and enthusiasm to the work which no other job had evoked. The prospect of dying with it unfinished was intolerable. No one would care to publish an incomplete history. He would die with the one task to which he had given heart and mind reduced to files of half-legible notes and reams of unedited typescript which would be bundled into plastic bags and collected for salvage. Sometimes the strength of his need to complete the book perturbed him. He wasn’t a professional historian; those who were, were unlikely to be merciful in judgement. But the book would not go unnoticed. He had interviewed an interesting variety of the over-eighties; personal testimonies had been skilfully interspersed with historical events. He was putting forward original, sometimes maverick views which would command respect. But he was ministering to his own need, not that of others. For reasons which he couldn’t satisfactorily explain he saw the history as a justification for his life.

The Skull Beneath the Skin

The Skull Beneath the Skin A Taste for Death

A Taste for Death The Children of Men

The Children of Men The Part-Time Job

The Part-Time Job Death in Holy Orders

Death in Holy Orders The Victim

The Victim Shroud for a Nightingale

Shroud for a Nightingale Talking about Detective Fiction

Talking about Detective Fiction Sleep No More

Sleep No More The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories

The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories Time to Be in Earnest

Time to Be in Earnest Original Sin

Original Sin A Mind to Murder

A Mind to Murder Cover Her Face

Cover Her Face Innocent Blood

Innocent Blood Devices and Desires

Devices and Desires Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales

Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales Death Comes to Pemberley

Death Comes to Pemberley The Mistletoe Murder

The Mistletoe Murder Death of an Expert Witness

Death of an Expert Witness The Private Patient

The Private Patient The Black Tower

The Black Tower Devices & Desires - Dalgleish 08

Devices & Desires - Dalgleish 08 Unnatural Causes

Unnatural Causes An Unsuitable Job for a Woman

An Unsuitable Job for a Woman The Murder Room

The Murder Room A Certain Justice

A Certain Justice The Lighthouse

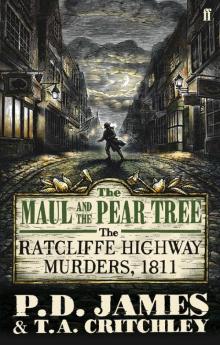

The Lighthouse The Maul and the Pear Tree

The Maul and the Pear Tree